After offering pleasantries to smooth over past criticisms, having called the 47th president the “most destructive in history”, one who had “dragged American and democracy through the mud”, our man in Washington might well have to deliver some uncomfortable news.

“Mr President, one more thing: my government has decided to fine the American tech giants 5 per cent of their global revenue because one of your citizens has been denying human-induced climate change, which is undermining public support for our clean energy future.”

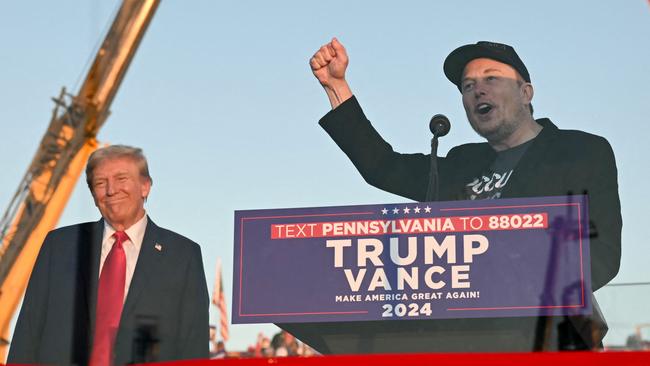

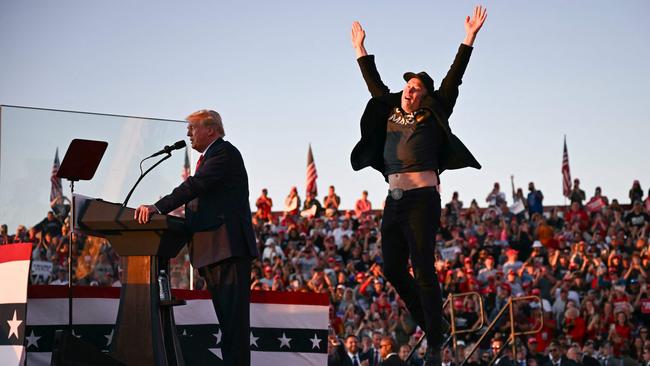

This idea that Google or Meta – or even more amusingly Elon Musk’s X, given his close relationship with Trump – would hand over hundreds of millions or billions of dollars to the Australian government is absurd, yet that’s exactly what the Combatting Misinformation and Disinformation Bill, currently before parliament, would require.

The more likely outcome is they would withdraw their popular services from the country entirely. The bill, which could well pass, must be one of the most ridiculous, unnecessary and pernicious ever before the federal parliament.

It’s not only appalling on traditional human rights grounds, paving the way for bureaucrats to stamp out arguments and claims, potentially factual, that elite opinion doesn’t like. But the timing is shockingly bad, jeopardising our relations with our most important ally and the incoming Trump administration at a time of significant geopolitical risk.

In September, JD Vance in an interview made clear he would look unfavourably on countries that sought to crack down on free speech, enshrined in the first amendment of the US constitution. “It would be insane that we would support a military alliance if that military alliance isn’t going to be that is not pro free speech,” he told YouTuber Shawn Ryan. “American power comes with certain strings attached, one of those is respect free speech,” he added.

He was referring to NATO but the comments could equally apply to Australia and AUKUS, which neither he nor president-elect Trump has said much about.

Labor’s bill, which explicitly provides for extraterritorial application, would impinge on Americans’ free speech, potentially preventing them from being heard in Australia. Quite aside from how unworkable such legislation would be, would Australians be able to use VPNs to get around the law? What about when they are overseas? The internet has no geographical location.

Trump is unlikely to look favourably on this legislation, which has been inspired by similar laws in the European Union, which only months ago sought to block Elon Musk’s long-form interview with Trump. A few days ago, Trump himself lauded the importance of free speech in a post on his Truth Social Platform: “If we don’t have free speech we don’t have a free country, it’s as simple as that; if this most fundament right is allowed to perish then the rest of our rights and liberties will topple one by one.” It’s hard to imagine he’d see Labor’s bill as wise legislation.

Of all the pressing problems Australia is facing, why is the federal parliament wasting valuable time on this bill? Throughout history major pieces of legislation have followed from public agitation: think votes for women or social security, or even tax reform. Where is the groundswell of popular support for this Orwellian censorship bill? There has been none.

The push, in Australia and abroad, has been driven entirely by elites. It began in earnest during and after the Covid-19 pandemic, when bureaucrats and government endorsed “experts” were shockingly humiliated, having pompously made pronouncements that proved wrong and rubbished those that were right.

Before 2020, the words misinformation and disinformation were barely heard in public discourse. This bill has nothing to do with stamping out child pornography, or incitement to violence, or grievous discrimination, issues well covered by other laws. It is entirely and eerily about governments exerting control over “the narrative”. It’s another step in the path towards recasting our societies to look more like China, where the government censors views and facts it doesn’t like.

Consider the last few years the range of issues that have been considered “misinformation” or “disinformation” by established opinion, which would be ripe for censorship under the sweepingly broad language of Labor’s bill, only to be deemed correct or at least debatable only months later. The origin of SARS-Cov2, Trump’s collusion with Russia ahead of the 2016 presidential election, Russia’s alleged blowing up of its Nord Stream pipeline, the efficacy of the Covid-19 vaccines.

The government would exercise great forbearance in enforcing these new laws, you say? Fat chance. Comically, in 2021 it asked the then social media platform Twitter to restrict a post by esteemed Harvard scientist Martin Kulldorff which argued that lockdowns were “ineffective”, among thousands of other posts including even jokes that mocked premiers. They would almost certainly do so again.

Indeed, the text of the bill astonishingly includes “opinion” within what can be classed as misinformation in Clause 13.

Opponents of free speech know that jurisdictions like Australia and Europe matter in their quest for greater censorship. The US constitution makes it practically impossible to pass a bill that abrogates free speech. But if Europe, Australia and Canada can broadly agree on what sorts of speech to stamp out, the global tech giants might simply oblige, rather than lose access to what are collectively large markets.

The pandemic illustrated that Australian governments already have more powers than most people realised, hidden in innocuous sounding little phrases in laws passed long ago. They do not need more.

Kevin Rudd’s first meeting with Donald Trump in the White House next year could be more awkward than you might expect.