Liberal Party’s proud tradition of advancing Indigenous reform

He said, “for far too long we have been crying out, and far too few have heard us”.

When people spoke about Indigenous issues, “they had noble words and sentiments”, but they were ultimately “blown away on the winds of indifference”.

Tragically, our First Australians have never had either the recognition they deserve or enjoyed the outcomes they deserve.

In his important book, Buraadja, Senator Andrew Bragg advocates for change as he charts a new trajectory for Australia.

He provides a historical and intellectual framework to work through the issues of reconciliation, taking the reader on a journey from the past, to the present, and into the future.

I do not agree with everything he wrote, but he challenges us to ask why.

The Liberal Party has a proud tradition of progressing reforms in Indigenous affairs.

In Robert Menzies’ words, “we took the name ‘liberal’ because we were determined to be a progressive party, willing to make experiments; in no sense reactionary but believing in the individual, his rights, and his enterprise.”

The success of Harold Holt’s 1967 referendum saw Indigenous Australians recognised for the first time in the census and the parliament empowered to make laws in relation to Indigenous people.

Malcolm Fraser championed land rights, with his then minister for Aboriginal Affairs, Fred Chaney, saying to Fraser, ‘“you know there’s no votes in this’, but we both agreed it was the right thing to do.”

Australia’s second longest serving prime minister, John Howard, may have wrestled with the implications of the 1996 Wik decision of the High Court, but he was, as Noel Pearson notes, the first Liberal prime minister to use the word “recognition” in his 2007 address on constitutional change.

Tony Abbott, in his 2013 speech to the Garma Festival in Arnhem Land, said “as far as I’m concerned, Indigenous recognition would not be changing our constitution, but completing our constitution”.

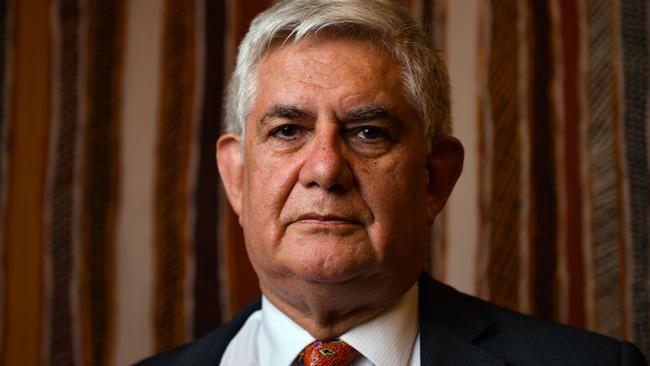

Ken Wyatt, the Minister for Indigenous Affairs, is the first Indigenous person to sit in the cabinet.

But despite the gains that have been made in Indigenous affairs over the years, we know there is still more to be done to ensure that every Indigenous young boy or girl growing up has access to the same opportunities as everyone else.

In recent weeks, Prime Minister Scott Morrison, in giving his Closing the Gap address, pointed out that while we are making progress with respect to preschool attendance, on other benchmarks, like life expectancy and incarceration rates, we are not where we want to be.

More funding for childhood education, city-country partnerships, data collection, among others, are all important but do not guarantee success.

While Buraadja covers the critical issues involved in Closing the Gap, its conclusion is that it is only part, but not the whole, story.

This is where Senator Bragg enters the contested space of the Uluru Statement and the Voice, advocating for it to be enshrined in the Constitution.

I will not go as far as Gladys Berejiklian or Steven Marshall, who launched this book in other states, by advocating for this type of constitutional change, but rather am more focused on the purpose and the goal that change is designed to achieve.

Change must unite us, not divide us, and needs to be bipartisan. Negotiation, consultation and flexibility is required. It cannot be a take it or leave it proposition.

Constitutional change in Australia, requiring a double majority, is historically very difficult to achieve.

Whatever form change ultimately takes, we cannot afford for it to fail.

As my colleague, Julian Leeser, chair of the Joint Standing Committee on Indigenous Affairs, has said, “the key issue is not words in the constitution, but whether it will genuinely give voice to Indigenous people across Australia on the issues that affect them most”.

There are national, regional and local elements to this process.

Mark Leibler, co-chair of the Expert Panel and the Referendum Council on Constitutional Recognition, recently reminded us it was Noel Pearson who said as far back as 2004, “only a highly conservative leader, one who enjoys the confidence of the most conservative sections of the national community, will be able to lead the country to an appropriate resolution”.

While many may seek to disagree with that comment, where we sit today it is the reality.

In Buraadja, Senator Bragg provokes, challenges, and educates.

Conscious of Pearson’s sentiment, Senator Bragg is determined in pursuit of change.

In doing so, he understands the Liberal Party’s proud past on Indigenous affairs is a powerful guide, offering hope for the future.

Josh Frydenberg is the federal Treasurer

Five decades ago, Neville Bonner was the first Indigenous Australian sworn into our parliament.