Let’s never have so many eggs in the China basket

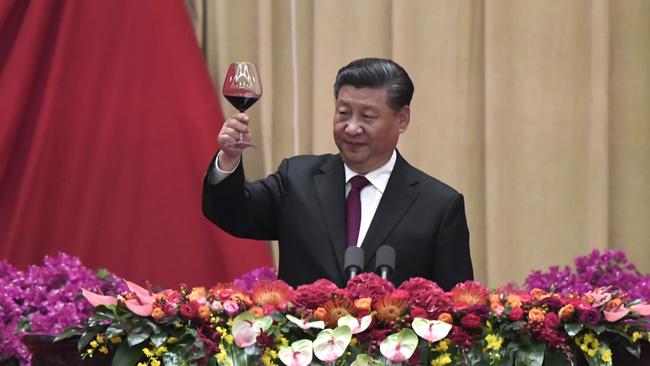

They were: “failure of climate change mitigation and adaptation; major natural disasters like earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions and geomagnetic storms; major biodiversity losses and ecosystem collapse; human-made environmental damage and disasters; and extreme weather events like floods and storms.” Climate obsession meant pandemics missed the cut. And Chinese President Xi Jinping missed the conference. He was busy keeping China’s unfolding coronavirus epidemic under wraps.

Beijing knows all about epidemics. There have been nine since 1967, four of which have originated in China.

Clearly, Xi knew of the threat well ahead of the WEF meeting because state media published a speech he delivered on February 3 referring to instructions he had given on January 7 detailing measures to fight the virus.

However, it took until late January, when the spread of infection could no longer be concealed, for the alarm to be officially raised.

How hollow now are the words of WEF founder Klaus Schwab, who used the forum to praise China for “playing a responsive and responsible role” in international affairs.

The same for World Health Organisation chief Tedros Adhanom, who applauded China’s work in containing the virus and for its transparency. Adhanom blatantly ignored the eight Wuhan doctors who, on January 3, were forced to confess to spreading false rumours when they were trying to alert the public to the danger.

But, to many masters of the universe gathered in Davos, China’s authoritarianism is to be admired.

Frequent attendee and former UN Framework Convention on Climate Change chief Christiana Figueres says China was “able to implement policies because its political system avoids some of the legislative hurdles seen in countries including the US”.

Better to give control over the lives of 1.4 billion people to one person than distribute it among cumbersome representative parliaments.

The Wuhan cover-up probably cost the world two months’ prophylactic time. Not only has this worsened people’s health prospects but it also has dealt a serious blow to the global economy’s immune system.

Adding to the crisis and, without notice, Saudi Arabia decided to abandon crude oil price support and flood the world with huge volumes of cheap oil. This has put $112bn of low-grade shale oil debt and renewable energy operators at serious risk of default.

The vulnerability of the global economy owes much to the corrosive influence of decades of collective economic policy thinking. Since the last financial crisis, rather than push for fiscal and monetary discipline, global institutions have kept the world economy on life support. Their fetish for easy money and debt has compromised economic resilience.

Rather than worry about supply and demand shocks, central bankers now fancy themselves as “climate rescuers of last resort”. Pity about Italian banks, which have remained in deep trouble and now threaten contagion and the survival of the eurozone. No; as fiscal reform became an ever-receding horizon, the banks worked with politicians and vested interests to socialise risk. They encouraged spending rather than saving, and they permitted borrowings beyond prudent limits.

US corporate debt has never been higher or its quality lower. Buoyed by the notion that serious economic setbacks were a thing of the past, gullible Wall Street investors priced risk at zero.

Business leaders also have ignored the moral hazard implicit in a “wink-wink, too-big-to-fail” understanding. They concentrated on share price, corporate social responsibility and sustainable investment. They meekly accepted the additional risk of government regulations and resorted to virtue signalling as a quid pro quo for a “social licence to operate”.

The result? A loss of appetite for new products and innovation, a boom in mergers and acquisitions and stock buybacks.

Seizing on this weakness, the Chinese monopolised much of the global supply chain. Incredibly, about 80 per cent of the ingredients used in the world’s pharmaceuticals are sourced from China.

This must change. As it does, growing economic and social stresses will visit Beijing. They will add to those that China is already facing from consistently unprofitable companies.

There are at least 20,000 “zombie” companies in China that are dependent on government subsidies and loans from state-owned banks to survive. In turn, there are multiple smaller suppliers who rely on them. Withdrawal of zombie support would create mass unemployment. This is a an enormous problem with unpredictable consequences.

The world is in recession. Official action will cushion the initial shock, but these are early days. Unemployment rates will escalate alarmingly, and banks and other credit providers face serious loan defaults as asset prices fall.

Wise leaders will not waste this crisis. While the health pandemic will end, the economic consequences will live on and confidence will take time to return. There will be no V-shaped recovery this time.

A clear lesson is how global groupthink has concentrated risk and left most nations with little or no ammunition to deal with the economic fallout.

A consequence for Australia’s policymakers is that even a revised $1 trillion debt ceiling may not be enough. And rather than satisfy globalist agendas, many countries will pursue self-interest. Australia should be among them. As a priority, it must encourage onshoring and diversification of markets and supply chains.

Such an economy requires a lean structure with the emphasis on global competitiveness. Tax, wage, environment, energy, education and social policies will all need a serious overhaul, with the emphasis on getting government out of the way.

This will be difficult for many of today’s leaders who have never experienced a serious recession. Scott Morrison was only 23 when Australia’s last recession finished.

Thanks to their education, many have embraced postmodern socialism as the solution. They are ill-prepared for philosophical change. But, if the present crisis does not convince our leaders of the dangers of big government and authoritarianism, nothing will.

Ahead of its January 21 annual meeting in Davos, the World Economic Forum released a report listing the top five risks by likelihood across the next decade.