He destroyed John Gorton as PM, then destroyed Bill Snedden as Liberal leader, blocked supply to the Whitlam government, told the governor-general to dismiss Gough Whitlam, became caretaker PM, won the biggest landslide election in Australia’s history – and then rolled the Treasury to impose full tax indexation upon the nation.

This was Fraser embodying his “great man theory of history”. That’s how the grand Australian experiment in tax indexation began. It was conceived in Whitlam’s demise and Fraser’s ambition. What did Fraser tell his party room? Radiating ebullience, Big Mal said: “We promised tax indexation over three years. Would any of you have believed we could do it in six months?”

They would have cheered. A new era of libertarian political giants were stomping the countryside. The year 1976 was remarkable – the enshrined Liberal Party project to remake a bitterly divided Australia.

It didn’t go to plan.

It is natural that economic critics of the Albanese/Chalmers tax redistribution say the ultimate lesson is that Australia can only solve the problem of fiscal drag (taxpayers paying more tax by moving into a higher marginal rate) by leaders summoning courage and introduced tax indexation. Hey presto, problem solved. Indeed, just under half OECD nations automatically adjust income tax systems to inflation. It means a hidden tax cut annually.

But Australia has already been there – in the 1970s it witnessed a stunning experiment of ambition, agony and abdication. The vital lesson cannot be missed. The theory of tax indexation is model perfection – but in practice it collides with the ugly obstacle of Australian political culture.

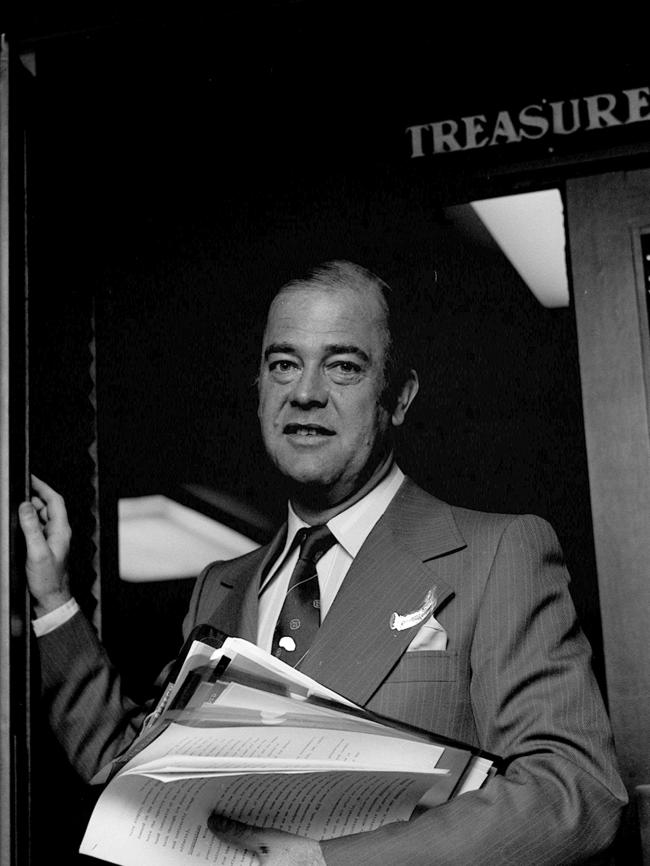

On May 14, 1976, new treasurer Phillip Lynch, a decent man but ineffective treasurer, wrote a letter drafted by Treasury to Fraser at Nareen. Treasury was deeply troubled; that meant Lynch was deeply troubled. Treasury told Lynch introducing tax indexation immediately, not phased in over three years, would weaken revenue and guarantee a far worse budget deficit. It would undermine the government’s pledge to reduce inflation from its 13 per cent high.

But within days the relevant cabinet committee backed in full indexation of all tax rates. Fraser won. He dismissed Treasury’s warning. The level of indexation was based on the CPI excluding the impact of indirect taxes. This was taxation over-delivery and overconfidence.

The subsequent Lynch budget said the tax indexation decision, effective from July 1, 1976, “represents perhaps the most significant reform of the personal income tax system in our time and certainly the most costly in terms of revenue forgone”.

It was values-based tax reform, heroic stuff. It would keep the government honest, kill fiscal drag, boost personal aspiration and lock in small government. What’s not to like? The government was bragging: “A change to the law will now be needed if a government seeks to increase effective real (tax) rates.” The cost was $1210m in a full year. The purpose, Lynch said, was “getting the government’s hands out of taxpayers’ pockets”.

Lynch said under Whitlam “the economy had been shaken to its foundations”. The Liberals had delivered a budget “for confidence” and “for reform” – hence tax indexation. Fraser was left distinctly unimpressed by Treasury but the feeling was mutual.

Fraser should have been happy – but he wasn’t (Big Mal was rarely happy). Indeed, Fraser soon had a serious problem. If annual tax relief was automatic, how could the government reap its political reward? It couldn’t. Tax indexation was good policy but unrewarded in politics. This was its curse: How many votes did it deliver? The next year, 1977, Fraser showed his true form by rolling out his bulldozer again.

Aiming for a late 1977 election, Fraser and Lynch then agreed on what they called a “revolutionary” tax cut – a tax cut designed to win electoral kudos – reducing the seven-step rate scale to three rates of 32, 46 and 60 per cent that later become the “fistful of dollars” in the 1977 campaign proper.

The moral: tax indexation wasn’t enough. It never satisfied Fraser’s impatient temperament or his political needs. But Fraser’s “revolutionary” tax cut was political overkill. He didn’t need this to win the election. Indeed, he got another landslide because Whitlam was still his opponent.

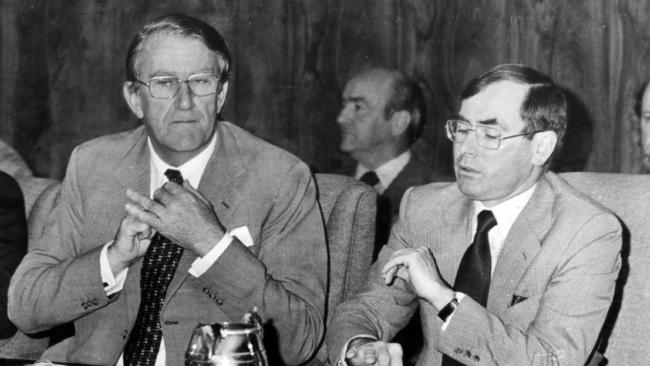

Fraser’s obsession about a discretionary tax cut meant he had misread the economy. The economic situation couldn’t afford his “fistful of dollars”. A new young treasurer, John Howard, was aghast when he grasped his inheritance. In early 1978 Treasury told Howard: the budget deficit was too large; inflation was still high. Taxes had to increase, a dagger at the heart of indexation.

Howard’s first budget was destined to be unpopular. For Fraser, it was an embarrassing retreat. Howard said later he now realised Fraser, not Lynch, was the “real author” of the 1977 tax cut. Howard and Fraser agreed on the abject reversal, a 1.5 per cent tax surcharge that would claw back some of the election tax cut. It shot the government’s credibility and shattered the integrity of its income tax cut. Howard later conceded his budget was “nasty and unpopular” – though it did help to restore the bottom line.

But tax indexation was sinking into the sunset. By 1980 the government had reduced the policy to half indexation. The fiscal pressures were too great and the political dividend was too small. At the 1980 election Fraser was still boasting about tax reform but it had a hollow ring – he was half dressed; it was now half indexation.

The final obliteration came in Fraser’s last term. The cabinet decision on abolition had been taken in April 1981. But on April 29, 1981, Howard sent Fraser a confidential memo. “As you know, I have never been an enthusiast about tax indexation, be it half or otherwise,” Howard said. But he was worried – it was the politics. Howard feared abolition of indexation would be seen as a tax increase, and therefore, another broken promise.

Howard said: “I think we have a done a great deal over the last year to rid ourselves of the ‘broken promise’ tag. This particular decision could well undo all of that work.” The critical point, however, is that despite this warning, Howard didn’t want the decision reversed. He recognised tax indexation was over. The experiment was dead. The treasurer was prepared to see it expire.

In power terms, Treasury won and Fraser lost. His former chief of staff, cabinet minister and historian, David Kemp, said the Treasury opposed tax indexation “believing it would weaken effective policy resistance to inflation”. Once implemented “it was a policy without much political impact”. Fraser decided “he should return to reliance on annual discretionary decisions”.

Kemp concluded that neither tax indexation nor the 1977 income tax cuts had “proved sustainable”. In fact, this extended saga, occupying most of the Fraser era, was a sorry record of misjudgment.

There were three factors in the death of tax indexation. The politicians wanted taxation power for themselves. They wanted the power in order to win votes and stay in office. Finally, they only saw the downside of tax indexation: missing its merits, they concluded it undermined other goals such as deficit reduction.

The world has changed but some things don’t change. Don’t expect the Albanese/Chalmers duo or the Dutton/Taylor duo to be dancing the Big Mal tax indexation quickstep.

You think Scott Morrison was a bulldozer? You haven’t seen anything. Consider our 1976 prime minister – big, tall, cumbersome and brutal. Malcolm Fraser was the authentic bulldozer.