It turns out very little, given the former US president advocates policies that only a few years ago were considered “left-wing”, making a mockery of the idea that some timeless unidimensional spectrum informs how we should understand politics.

It’s really all just name-calling nonsense, as US politics demonstrates. Trump is in favour of higher tariffs on imports and a foreign policy anchored in isolationism, which were considered left-wing positions during the presidency of Republican George W. Bush less than two decades ago.

On the other side of the divide, President Joe Biden’s administration is in favour of empowering government agencies to censor “misinformation”, a position diametrically opposed to the anti-censorship stance of Democrats a generation or two ago.

For most of the 20th century it was “the right” in favour of political censorship.

In the US, as in Australia and throughout the world, the left-right dichotomy has become a divisive delusion, a legacy going back to who sat where in the National Assembly during the 18th-century French Revolution that has no relevance to the complexity of modern political life.

Modern political parties promote a hodgepodge of policies that bear little relationship to each other. Why, for example, should someone who supports the voice or abortion necessarily be in favour of higher taxes or using the military to “spread democracy” abroad?

What individual political leaders advocate at any given time and place determine the left and right, far more than any underlying ideology.

Lockdowns during the pandemic, for instance, became identified with left-wing politics in the US purely because Trump at one point opposed them – even though socialist governments in Mexico and Sweden roundly rejected them. “Ideologies do not define tribes, tribes define ideologies; ideology is not about what (worldviews), it is about who (groups); there is no liberalism and conservatism, but liberals and conservatives,” write Hyrum and Verlam Lewis, two American politician science academics (and brothers), in a provocative new book, The Myth of Left and Right.

We are social creatures who tend to feel strongly about one particular aspect of a political party’s platform, and then feel obliged to support the rest of it. Yet there is far more disagreement within political parties than between them.

“Why do we refer to Milton Friedman (a Jewish, pro-capitalist pacifist) and Adolf Hitler (an anti-Semitic, anti-capitalist, militarist) as right-wing when they had opposite policy views on everything?” the authors ask.

Of course, tribalism is often determined by social background and governs most political interaction. Julian Assange is widely perceived as left-wing in Australia, but right-wing in the US, simply because he infuriated the Democratic Party in the US by releasing its embarrassing private emails before the 2016 election.

Members of the two warring tribes like to tell themselves stories to justify their positions: leftists advocate for “change” and “progress”, while those on the right apparently “conserve”.

So why, then, do conservatives support capitalism, the most intrinsically revolutionary economic system ever devised?

Meanwhile, the supposedly pro-change left has for decades fought globalisation to maintain national and indigenous cultures.

The “left” is also for bigger government (except in the US for issues relating to policing and illicit drug regulation).

Why were Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton – Democrats allegedly in favour of bigger government – the most fiscally conservative presidents in half a century? Meanwhile, Ronald Reagan, a champion of limited government, increased US debt and deficits more than any other administration outside war time.

As for religion, for much of the 19th and 20th centuries, Christian socialism was the predominant combination; the somewhat bizarre relationship between faith and free-market ideology developing much later.

Private banking, once the enemy of left-wing parties everywhere for a multitude of philosophical reasons, is now far more comfortable with parties of the left. Democrats in the US get far more donations from Wall Street, while the Labor Party has been the best friend to Australia’s funds management industry.

Italy’s “far-right” Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni, was recently attacked by mainstream media outlets for proposing a tax on bank super profits, something Ben Chifley (one of Australia’s most left-wing leaders) would have been proud of.

Cynicism about mandatory vaccination was more common among those who considered themselves left-wing until Covid-19, when it became a “right-wing issue” across much of the West.

Left-wing China, meanwhile, was one of the few nations not to mandate Covid vaccines. Maybe Xi Jinping is right-wing?

The left-right dichotomy serves two purposes. First, it enables many of us to feel righteous and principled – even though the vast bulk of political participants are really tribal lemmings without any real beliefs except, perhaps, for personal career advancement.

Second, it provides a simplistic framework to dismiss people we don’t like. Because the bulk of those in the media and academia now consider themselves “left-wing”, one almost never sees individuals described that way. By contrast, the pool of alleged “right-wingers” has exploded.

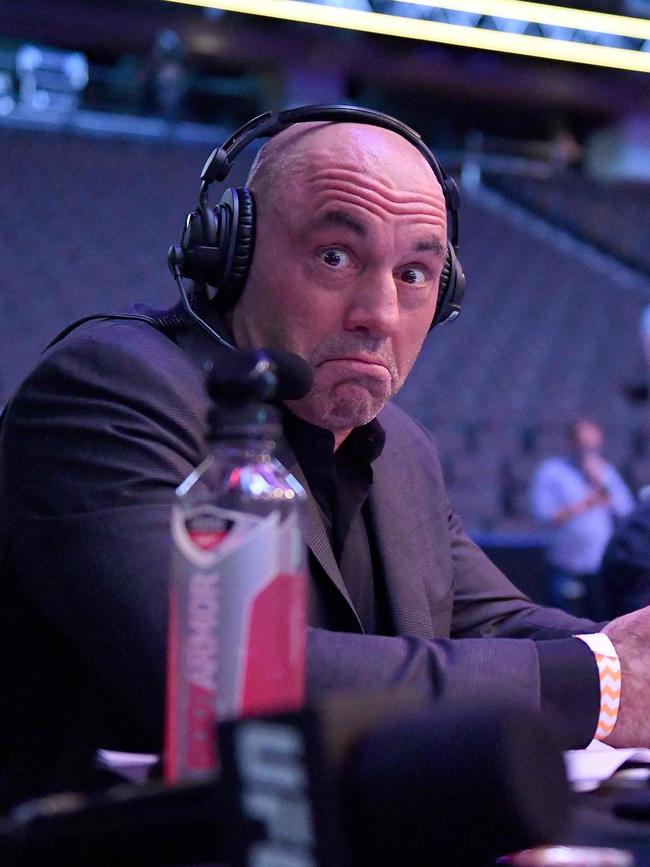

Elon Musk, who openly supported the Democrats, is now “right-wing” because he wasn’t enthusiastic about the war in Ukraine, which is currently a “left-wing” cause. The top US podcaster, Joe Rogan, who openly supported Bernie Sanders, is now regarded as “right-wing” because he questions compulsory Covid-19 vaccination.

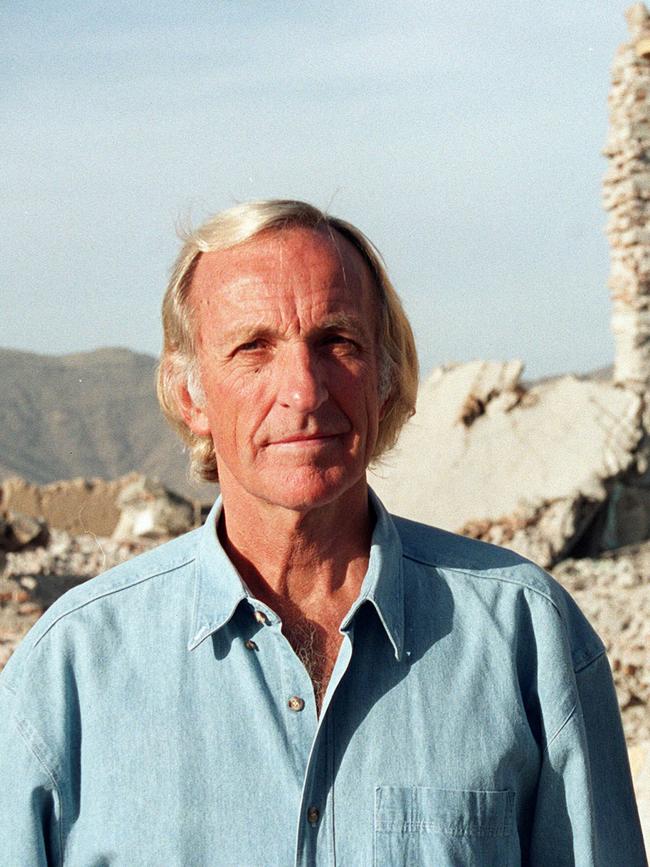

Germaine Greer has also been called “right-wing” for suggesting trans women aren’t real women. In a similar vein, a powerful essay by John Pilger, published last month about Western propaganda, could just as easily have been written by Tucker Carlson.

But Pilger remains firmly associated with the “left wing” because he’s in the “right” tribe, while Carlson is “right-wing” because he’s in the “wrong” tribe.

If the term “right-winger” has any meaning at all, it appears to be one that dissents from whatever official orthodoxy prevails at the time for any given policy.

Whatever, the terms are highly divisive and it’s time to move on from this meaningless division. Individuals have complex views and they should be treated on their merit.

You’ve probably heard Donald Trump described as “right-wing” or “far-right” even. But what does this actually mean?