Labor’s voice failure won’t be forgotten at the ballot box

The member for Paterson retained her seat comfortably in 2022, but that was before anyone was told about the offshore wind zone that would occupy a stretch of ocean 1½ times larger than Greater Newcastle.

That wasn’t the only surprise.

The voice referendum was announced after the polls had closed.

It was rejected by 70 per cent of voters in Paterson, one of 56 Labor-held seats that said no to Anthony Albanese’s signature first-term policy.

The decision to pursue a single lost cause at the expense of everyday concerns exposed the Prime Minister as out of touch with vast swathes of Labor’s heartland long before his unfortunate decision to invest in prime coastal real estate.

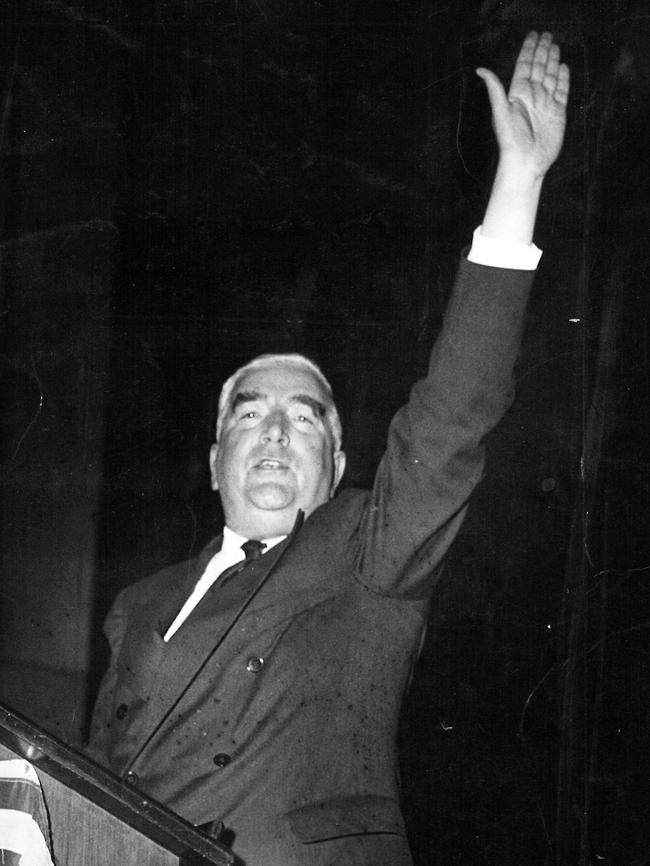

At a time such as this Labor needs a prime minister such as Bob Hawke, a leader with finely honed interpersonal skills, sharp political instinct and emotional intelligence who could make himself at home in any front bar.

Instead it has Albanese, who is unable to read the room and seemingly incapable of passing the pub test in any establishment that doesn’t sell craft beer.

In 2022, former Labor adviser Lachlan Harris declared Albanese’s everyman persona his greatest strength in an era of scripted politicians.

Albanese’s colleague Tony Burke ranked him as “the closest we will see to a Hawke both in leadership style and in authenticity”.

The referendum ended any illusion that Albo is a man of the people.

If any Australians were losing sleep because of anxiety about the constitutional status of Aboriginal Australians, they were vastly outnumbered by those kept awake worrying about meeting mortgage repayments.

Yet Albanese chose to lavish his limited political capital pushing an esoteric solution to an abstract problem, using language foreign to most voters.

Conventional wisdom suggests voters are prepared to overlook rookie errors in a first-term government and give it a second chance. Yet Albanese’s referendum misjudgment is not one of those stories that flares for a week before disappearing from headlines.

For 15 months the Prime Minister and a rag-tag bunch of finger-waggers hectored people who had watched as an assortment of jumped-up nobodies was given airtime to trash-talk their country. Two and a quarter centuries of Indigenous misfortune dumped on the heads of white people who could expect to pay reparations for untried crimes allegedly committed by their distant ancestors.

It mattered not if your ancestors were soldiers with the First Fleet or refugees escaping from communist Vietnam. Your right to be accorded the same respect as every other citizen was about to be annulled in the Constitution.

People don’t easily get over that kind of bullying. Wounds opened by the voice debate are still raw among the people you run into on steak night at the Lithgow Workers Club, the Olary Hotel or any place where Australia Day is celebrated with unabashed enthusiasm.

Losing a referendum is not always a career-ender.

Robert Menzies failed to get the 1951 Communist Party dissolution referendum over the line early in his second term yet he remained in office for another 15 years. Hawke lost the referendum on the interchange of powers and four-year parliamentary terms in 1984 but won the election on the same day.

The voice falls into a different category. It exposed the fault line that has broken through in almost every Western democracy between the university elite, which controls most civic institutions, and the rest of Australia, which is trying to control their own lives free of incursions from the state.

Few, if any, elections today are determined by party loyalty or abstract notions such as left and right. They are fought between those who abide by institutional wisdom on matters such as gender, race and climate change and those who trust common sense.

The great tectonic shift has been changing the political landscape for more than 30 years.

John Howard’s landslide in 1996 was due in part to Liberal Party gains in Labor’s traditional heartland.

Labor, on the other hand, has turned previously marginal inner-city electorates such as Adelaide into safe seats.

Peter Dutton is poised to make the largest assault on the Labor heartland since Tony Abbott in 2013, when the Liberals captured blue-collar seats such as Lowe.

In fact, Dutton may enjoy a clearer run than Abbott or Howard. Dutton’s courage in opposing the voice in the face of opposition within his own party put runs on the board in the parts of the country where the voice was regarded as a proxy for everything woke.

Crucially, outsiders now have the language to voice their common concerns and unite them in a common cause.

The word woke was unfamiliar to most Australians in 2022. Now it’s common currency and is used by the Opposition Leader almost daily.

Terms such as elite are understood more widely and precisely. The voice referendum made it clear to voters whether they were insiders or outsiders and which politicians were watching their backs.

The concept of the legacy media would have been unfamiliar to most people before Covid. Now it is recognised as a hostile force that conspires with the powerful to censor and lie.

Donald Trump’s election has changed things, too. His industrial slaughter of sacred cows in the US has put progressives on the defensive here too. Sooner or later, the dissonance between voting patterns at the referendum and federal elections will be resolved.

The Liberals will face an uphill battle to retain Bradfield, the only Coalition seat to vote in favour of the referendum.

Labor’s challenge is greater.

The disparity between the No vote and support for Albanese in 2022 is widest in the NSW seats of Hunter (ALP 54 per cent two-party preferred, No vote 70.9 per cent, a gap of 16.9) and Paterson (16.8), closely followed by Lyons in Tasmania (16.5) and Blair in Queensland (15.1).

The 25 Labor seats where the Yes vote was higher than the national average included ALP strongholds such as Gough Whitlam’s old seat of Werriwa, Shortland and McMahon, where the incumbent would retire if he felt the slightest degree of responsibility for atrocities such as the Hunter offshore wind project.

The seat where the Yes vote and Labor’s vote are most closely aligned is Grayndler (Yes 74.6 per cent, ALP 78.9 per cent), suggesting the Prime Minister will comfortably win his seat. Whether he retains his title is another matter.

Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen’s thoughtless decision to anchor rows of giant wind turbines off the coast is not the only reason Labor MP Meryl Swanson should start looking for another job.