“If protesters enter your classes,” wrote the university’s provost, “we ask that you refrain from intervening and allow them to share the information they wish to.” The only action staff can take, should they wish to prevent that occurring, is to postpone the class or cancel it altogether.

It is hard to imagine a greater affront to the academic ethos. Taxpayers do not fund universities so that students can be subjected to compulsory indoctrination. They fund them to deliver high-quality teaching, provided by staff who are sufficiently competent that they can help students master complex and often contentious subjects.

Tirades about the Middle East by protesters who lack any detailed understanding of the area, much less the academic qualifications required to teach its history and politics, are starkly at odds with that standard. That nothing has been done to ensure the protesters’ statements are challenged by alternative viewpoints compounds the injury, breaching the university’s obligation to present controversial issues fairly and objectively.

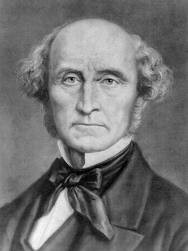

But it is not only the academic ethos the decision offends; it is also the freedom of expression. As the great Victorian liberals, led by John Stuart Mill, emphasised, my freedom to speak imposes no obligation on you to listen: “If we vindicate the right of a man to say what he pleases, we must also vindicate the right of his neighbour not to listen to him if he pleases.”

And if free speech promotes the search for truth, it is at least partly because speakers must compete for listeners, including by making what they have to say worthwhile.

Yes, that competition is highly imperfect: the insight of geniuses can be drowned out by the chatter of fools. But it is hardly an accident that the greatest – and most dangerous – lies have been told by dictators who can herd their subjects into vast stadiums and force-feed unvarnished drivel to unwilling audiences.

Of course, competing for listeners has always been difficult, as every writer knows. It is even harder in today’s world, where it is not content that is scarce but the time to absorb it. Herbert Simon, a polymathic scholar who went on to win the Nobel Memorial Prize for economics, was prescient when he warned, in a survey on the likely impact of computer networks written in 1971, that “a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention – and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of sources that might consume it”.

That makes the university’s decision to allocate students’ scarce attention to zealots, who might otherwise struggle to find customers, truly extraordinary – and even more so as it comes directly out of time spent learning.

To say that is not to deny that some students might want to hear the protesters’ case. It is, however, easy for them to do so: they simply have to stroll over to the picket lines. As a result, the only students this decision constrains are those who would, if they could, give the protesters a wide berth.

One might have thought the university would explain why those students deserve to be stripped of the right to make that choice. It has done no such thing. Nor has it devoted a single word to explaining why it believes assaulting those students’ rights will help restore campus harmony. And it has been utterly silent on why it is acceptable to have presentations that are entirely one-sided, rather than insisting on the alternative view also getting an airing.

Those silences reflect the moral vacuum, and intellectual poverty, that has engulfed the leadership of so many of our universities. But what is no less striking is that the university’s faculty has not risen up in revolt. After all, faculty members’ rights are being trampled on too. Moreover, they have a professional duty to protect the university’s goals and values, not least by upholding the quality and integrity of instruction. A decision that manifestly trashes that objective ought to provoke howls of indignation.

There are, no doubt, some academics who feel powerless, as ever more decisions are taken by the burgeoning mass of university administrators: since 1992, the number of senior executives per staff member at our universities has more than doubled. But there are also other academics who feel threatened.

Their fears are not irrational. The protesters don’t just want to cram their views down recalcitrant throats; they want to silence opponents. To stand up for intellectual freedom is to invite cancel culture’s storm troopers to one’s door. And when they show up, it won’t be our universities’ leaders who bar the way.

Nor will it be those academics – and there are many – who are little more than professional protesters with advanced degrees. A glance at history suggests their attitude should come as no surprise: far more often than one might wish, the face of evil has worn the mask of learning.

For every Solzhenitsyn there were, in the Soviet era, hundreds of Fadeyevs, just as the Heideggers in Nazi Germany far outnumbered the Bonhoeffers. Going further back, it wasn’t the monarchs who were the most ardent supporters of laws that, in early Modern Europe, imposed savage penalties on those who failed to attend church; it was an ascendent class of clerics, who used the laws to entrench their privileges, eliminate rivals and enjoy an easy life.

Equally, it wasn’t the popes who heaped abuse on the Roman Jews who, as of 1584, were compelled to attend weekly sermons in which Judaism was denounced as the religion of deicides and child-murderers; it was counter-reformation scholars such as Giulio Bartolocci, who was one of the most important Hebraists of the early modern period.

Those scholars weren’t squeamish about compulsion: as Federico Franzini’s 17th century guide to the sermons indicated, “So as to stop the Jews from sleeping, and keep them humble, there is a policeman with baton in hand, who fines the inattentive and pummels the disorderly”.

Now it is the Jewish students and teachers at La Trobe who will be forced to attend diatribes they find profoundly offensive – not in the Europe of centuries ago but in today’s Australia. Charles La Trobe, Victoria’s first governor, a man of high principles and strong cultural interests who worked tirelessly to establish the colony’s first university, would have been appalled, not just at the conduct of the university that bears his name but at the state and federal governments that have stood mutely by.

We should be appalled too. That it happened is an outrage. That it is being allowed to continue is worse than an outrage: it is a national disgrace.

Last week, Melbourne’s La Trobe University instructed its teaching staff that pro-Palestinian protesters have a right to address any class of their choosing for up to five minutes.