Kylie Moore-Gilbert: Iran wants a hostage deal it can bank on

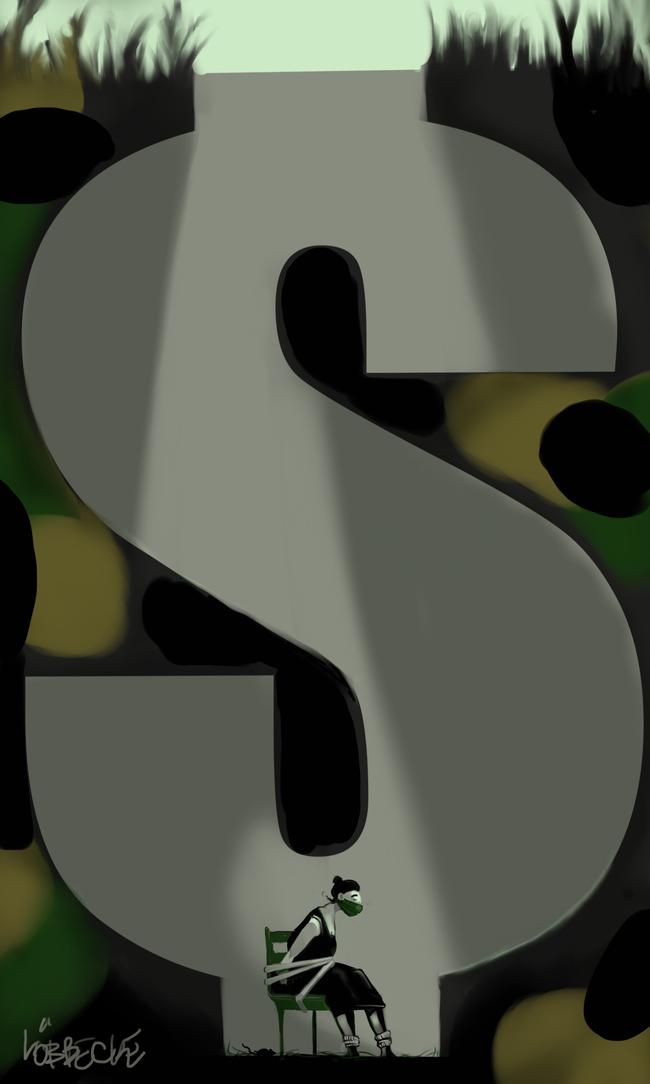

Hostage diplomacy occurs when a detaining nation is prepared to release a detained foreigner (or provide more lenient treatment) in return for concessions from the detainee’s nation. It is an asymmetric weapon of diplomacy.

A common pretext for detention of foreigners for hostage diplomacy purposes is engagement in espionage or prohibited activities.

If the person detained was engaged in espionage it is hardly likely that the detainee’s nation is going to admit that. And even if the detainee publicly confesses to espionage, the confession could have been made under duress.

To muddy the waters further, a person arrested for espionage may have been acting on behalf of a third-party nation. Israel’s Mossad is active in Iran using third-nation passport holders for espionage and agent recruitment purposes. (Israelis are banned from entering Iran and anyone with connections to Israel should definitely not travel to Iran.)

A further complicating factor comes about when a person holds dual or multiple passports. Moore-Gilbert has dual Australian and British nationality. Iranians regard Australia favourably, but are less enamoured of the UK.

Roger Cooper, a British businessman imprisoned in Iran from 1985 to 1991 on espionage charges, wrote a book about his experience, Death Plus Ten Years, in which he said that guilt or innocence did not come into the equation. After he was arrested, his interrogators just assumed he was guilty and cherrypicked information that supported their assumption.

Most of Iran’s foreign detainees have been ethnic Iranian dual-passport holders, including Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, Morad Tahbaz, Kamal Foroughi, Aras Amiri, Kameel Ahmady, and Anousheh Ashouri.

I visited Iran in 2016. Because I did not have time to apply for a visa, I took advantage of the “visa on arrival” option available to Australians (but not to the British, Canadians or Americans).

Immigration officials were very helpful when they saw I was travelling on an Australian passport.

Hi Twitter.

— Free Kylie Moore-Gilbert (@FreeKylieMG) September 17, 2020

Today, we’re sharing some precious memories of #KylieMooreGilbert from Jenny, one of Kylie’s former teachers in #Bathurst

Along with her story, here's an early pic of Kylie, every inch the typical Aussie teenager 🥰 1/ pic.twitter.com/IEAncLvF9e

And I found Iranian officials to be generally friendly and helpful throughout including, surprisingly, members of the notorious Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Even so, I was careful not to take pictures of military installations or the Natanz nuclear facility, or ask questions about sensitive issues. However, for obvious Iranian propaganda reasons I was allowed to take as many photos as I wanted at the old US “Den of Spies” embassy in Tehran.

There seem to be three possible reasons for Moore-Gilbert’s detention.

First, she did something Iran’s Intelligence Ministry, believed to be espionage-related. They may, for example, believe she was talent-spotting or obtaining information for Mossad.

Given her research background, she may well have tried to obtain information for research purposes that Iran regarded as sensitive, or tried to collaborate with an Iranian to gain information to further her university research.

Second, she did nothing untoward and was detained to get some of the Australian sanctions against Iran lifted.

From 2008 Australia has imposed sanctions to oppose Iran’s nuclear and missile programs, including relating to gold, precious metals and arms. Further sanctions in 2013 limited Australians from doing business with oil, gas, petroleum and financial sectors there. Iran would like some of these lifted.

Third, her detention related to her British nationality.

What Iran wants most from the UK is the release of the substantial funds owed to Tehran from an uncompleted 1970s arms deal. (Detained British dual national Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe was allegedly told by her interrogators that her detention was linked to the arms deal.)

The background to the third and most likely reason is as follows. During the period from 1971 to 1976, the Shah of Iran paid the UK £650m in a major arms deal under which UK government-owned International Military Services Ltd contracted to supply 1500 state-of-the-art Chieftain battle tanks and 250 repair vehicles to Iran. Only 185 tanks had been delivered when the Shah was overthrown in the 1979 Iranian revolution.

In 2001, Iran won its case for a refund from IMS which the following year paid £382.5m to the British Court Funds Office. This, with interest, now amounts to more than £500m.

How much Iran will actually receive is still disputed. IMS has used complex legal actions and EU sanctions to block the payment of any money to Iran.

In 2013, Iranian officials travelled to Britain to progress High Court action to obtain access to the money but had their visas revoked on arrival at Heathrow Airport. They were detained a few days then deported.

733 days.💔

— Free Kylie Moore-Gilbert (@FreeKylieMG) September 15, 2020

You can help bring her home. Visit https://t.co/PD14WDXgZk for more info.#KylieIsUs pic.twitter.com/tggXVCrnNM

In January 2016 (pre-Trump), the US refunded $US400m to Iran for undelivered US military equipment. It was associated with the release of four Iranian-Americans, including Washington Post journalist Jason Rezaian. This could be viewed as precedent for a UK refund.

However, the UK is probably dragging its feet over release of the money owed to Iran due to ongoing pressure not to do so from the Trump administration, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Israel – all of whom want to contain Iran’s influence in the Middle East.

In summary, there may or may not be any substance to Moore-Gilbert’s detention, but probably the best prospect for her early release lies through hostage diplomacy and Australian pressure on the UK to release those Iranian funds.

Clive Williams is a visiting professor at the Australian National University’s Centre for Military and Security Law.

Australian Kylie Moore-Gilbert’s detention in Iran since September 2018 on espionage charges may eventually be resolved through “hostage diplomacy” – but more on her situation later.