John McEwen’s postwar success has lessons for us post-Covid

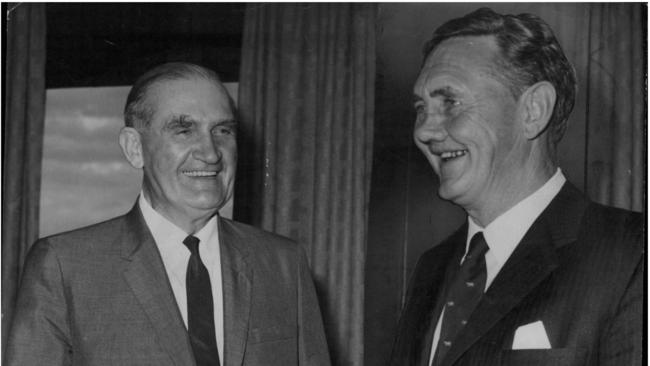

But McEwen, whose statue in Canberra’s parliamentary zone was unveiled last week, wasn’t accidental. He was, in Paul Keating’s words, the pre-eminent conservative politician of the second half of the past century. That is, more important in a policy sense than Robert Menzies himself.

My new reflections of John McEwen’s contribution to building our nation are, in part, an attempt to set the record straight on a political titan who has been derided by the left and the right — but more importantly an attempt to test whether his political formula, known as McEwenism, has relevance today.

McEwen was in large part responsible for our extraordinary postwar prosperity through policies of rural reconstruction, immigration, increased exports and support for manufacturing.

Yet he rarely if ever features in economics, international relations or political science lectures in our universities and his legacy has been minimised as outdated protectionism — a failed approach unsuitable for a modern, supposedly diverse economy.

This is untrue. McEwenism is about nation building. McEwen’s “protection for all” at its simplest was an economic expression of egalitarianism. His contribution and vision for our nation extended beyond ensuring farmers, manufacturers and workers were able to make a living. McEwen recognised national interest is best served with strong, prosperous and populous regions.

William McMahon and Gough Whitlam, who began the dismantlement of McEwen’s policy framework, both lacked McEwen’s pragmatism — his focus on the real world, not the textbook. The development and industrialisation of Australia driven by McEwen and supported by Menzies has been deconstructed and derided to the point where academics now question the social, economic and political contribution he made.

Denigrating McEwen as an “agrarian socialist” misses the point. He was a leader interested in outcomes, not in an imagined utopia found at either end of the political spectrum. After World War II, he knew the nation could no longer rely on Britain and had to forge its own way.

In 2020, Australia has similarly awakened to the weakness in our domestic economy and in our sovereign capacity, and to the shortsighted policies that have resulted in an economy that is without sufficient breadth or depth. It is instructive to reflect on Australia’s post-WWII recovery.

For McEwen, principles of full employment meant backing primary and secondary industries domestically, and fighting for an international rules-based trading system that did not just favour the big guys. That approach holds true. Apologies to Adam Smith and Josh Frydenberg, but the invisible hand of McEwen lies behind Australia’s COVID-19 recovery response. At a national level, it would seem we are all McEwenists now.

A new focus on full employment has been laid out by the Reserve Bank of Australia, which has now raised the bar that the measure of the success of our economic policy settings should be our employment rate.

Essential policy imperatives that were the focus of McEwen are still front and centre. Regionalism, decentralisation, employment for all, growing our share of international trade, securing and defending our borders and way of life, and maintaining our independence as a sovereign nation are among our shared values.

McEwen did not support propping up inefficient industries but he believed “it is also necessary to take account of things beside efficiency — there was one constant thought in my mind: we had a workforce to employ”.

COVID-19 has exposed two critical issues for Australia — our decreased manufacturing capability and our over-reliance on fragile global supply chains to source critical goods. We need to ensure regional Australia is the focus for investment by backing existing players to grow and backing new advanced manufacturing plants and capability.

McEwen’s thinking, his idea of freedom to be “one’s own boss”, is still a core principle for farmers and small businesses. McEwenism and the policies he chose to implement were not popular at the time, but they were popular subsequently because Australians were proud of standing on their own two feet, and because the wealth created set the nation up for a long period of prosperity.

These policies articulated our identity as a modern, fledgling, first world industrialised nation, secure, sovereign and prosperous.

We are again facing great uncertainty. A global pandemic and a trade war between our strategic ally and our economic partner threaten our national interest like never before.

Out of this global uncertainty and necessity we should embrace McEwen and reimagine our nation so that we re-emerge and rebuild to again become that sovereign, prosperous nation.

John McEwen: Right Man, Right Place, Right Time by Bridget McKenzie, Connor Court.

On this day 53 years ago, prime minister Harold Holt went for a swim at Portsea and didn’t return, resulting in the Country Party’s John McEwen becoming our accidental prime minister.