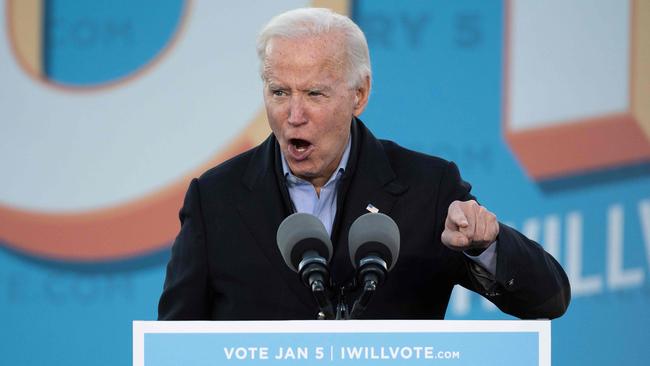

Joe Biden’s foreign policy reset likely to be Obama lite

Joe Biden’s administration is likely to be more popular around the world than the Trump administration, but it’s far from clear that it will be more effective.

If, as seems probable from the incoming president’s appointments (such as former secretary of state John Kerry), Biden turns out to be Obama lite, there’s likely to be plenty of fine words but not much strong action.

As vice-president, Biden spent several days in Australia in July 2016, and gave an address on the Australia-US relationship at Sydney’s Paddington Town Hall. It was a warm and sometimes moving evocation of our long alliance, the comradeship of the battlefield, and the ready familiarity of the American and Australian peoples. But in a hint, even then, that he could be ready for retirement, he tarried too long at Taronga Zoo with his grandchildren, was late for a reception at Admiralty House and gave a rambling talk way beyond the allotted time.

There’s little doubt that he’s a decent man who believes in the US and its global leadership, and who is as centrist as it’s possible to be in the contemporary Green New Deal obsessed Democratic Party. But Biden clearly is past his prime and he tellingly counselled caution against the strongest foreign action of the Obama era, the strike on Osama bin Laden.

It’s almost 1½ years since Biden’s big foreign policy speech at the City University of New York in July 2019, but nothing he has said subsequently suggests that this speech won’t turn out to be the Biden blueprint.

Initially, there’s no doubt that other leaders and the world’s media will welcome president “I won’t be Donald Trump”. But while the atmospherics of summits will improve, the world’s challenges will remain.

Biden almost certainly won’t dismantle Trump’s wall because it started under Barack Obama, but he’ll celebrate the US as a great immigrant success story. He will almost certainly keep pressing allies (other than Britain and Australia) to spend more on their armed forces, but he’ll stop the anti-NATO rhetoric. And while he’ll keep reminding his listeners that he has spent more time with China’s President Xi Jinping than any other global leader (as vice-presidents they each had a week together in the other’s country), there’ll be no early dismantling of Trump’s tariffs as Biden, too, tries to rebuild the US’s industrial base.

As with so many contemporary leaders, Biden’s specialty is trying to be all things to everyone. Hence it’s far from clear what action will emerge from his rhetoric of juxtaposed and sometimes contradictory ideas. As with Obama, he wants the US to remain the world’s leader; but also like Obama, he stresses that the US can’t lead on its own. Translated, this means the US will lead only where other countries are prepared to follow.

As he put it in 2019, “the Biden foreign policy agenda will place America back at the head of the table, working with our allies and partners to mobilise global action on global threats, especially those unique to our century”. On the one hand, he said, “I will never hesitate to protect the American people including, when necessary, by using military force.” On the other hand, he said, “I will make it my mission to restore American leadership and elevate diplomacy as our principal tool of foreign policy.”

So Biden will rejoin all the global accords that Trump left, especially the Paris Agreement and the Iran nuclear deal. He says he wants to make China cut its emissions as much as everyone else and to stop Iran going nuclear but neither outcome was looking likely under these Obama-era deals; and the only pressure Biden seems keen to use — moral pressure — normally doesn’t work against aggressive dictatorships.

There’s no doubt that with Britain hosting the next climate change conference in Glasgow and with a climate change enthusiast in the White House, the heat will come on Australia to adopt net-zero emissions by 2050. My sense is that to keep the peace with our main allies, our ultra-pragmatic Prime Minister will concede, knowing that it’s 10 elections away, and push on regardless with his plan for more gas-fired baseload power.

With Xi set on being the leader who restored Beijing’s control over Hong Kong and Taiwan, it could fall to Biden to determine whether the US alliance system stands or falls. A failure to back Taiwan would destroy faith in the US’s readiness to take risks for its allies. Yet it’s hard to see Biden taking serious US casualties and risking escalation if Japan and Australia aren’t prepared to help.

This is where Australia’s readiness to engage in contingency planning with the US military and to commit credible forces could help to shape the destiny of the wider world. There will be a huge lobby for not taking sides between our strongest ally and our biggest trading partner; but not standing against the destruction of a free country would guarantee a world dominated by China.

And because the US could keep to itself in its own hemisphere more readily than us, Australia has an even more acute interest in the survival of a free Taiwan. Even so, it’s always a mistake to underestimate the US and its people’s capacity to get ahead regardless of their government.

Given the Biden administration’s stated priorities, it’s hard to be optimistic about where America is heading.

Ross Fitzgerald is emeritus professor of history and politics at Griffith University and the author of 42 books.