While living standards are clearly slipping, in many ways inflation is the government’s friend. In all likelihood, there will be a second budget surplus next year.

What the National Accounts clearly demonstrated is that the economy is flatlining, while GDP per capita continues to go backwards. Real household disposable income declined by 1.7 per cent over the September quarter, the fourth consecutive quarterly decline. Since its peak in the third quarter of 2021, real disposable income has fallen by over 8 per cent.

The principal reasons for this dismal outcome are: inflation, rising mortgage rates and a rising tax take. While inflation abated somewhat in the quarter, interest paid on mortgages rose by close to 8 per cent while income tax paid by households also rose by close to 8 per cent.

The insufficient growth in the economy, as well as the increase in the population due largely to immigration, has sealed this depressing result. It’s hardly surprising people are feeling grumpy, something that is being reflected in the surveys of consumer sentiment.

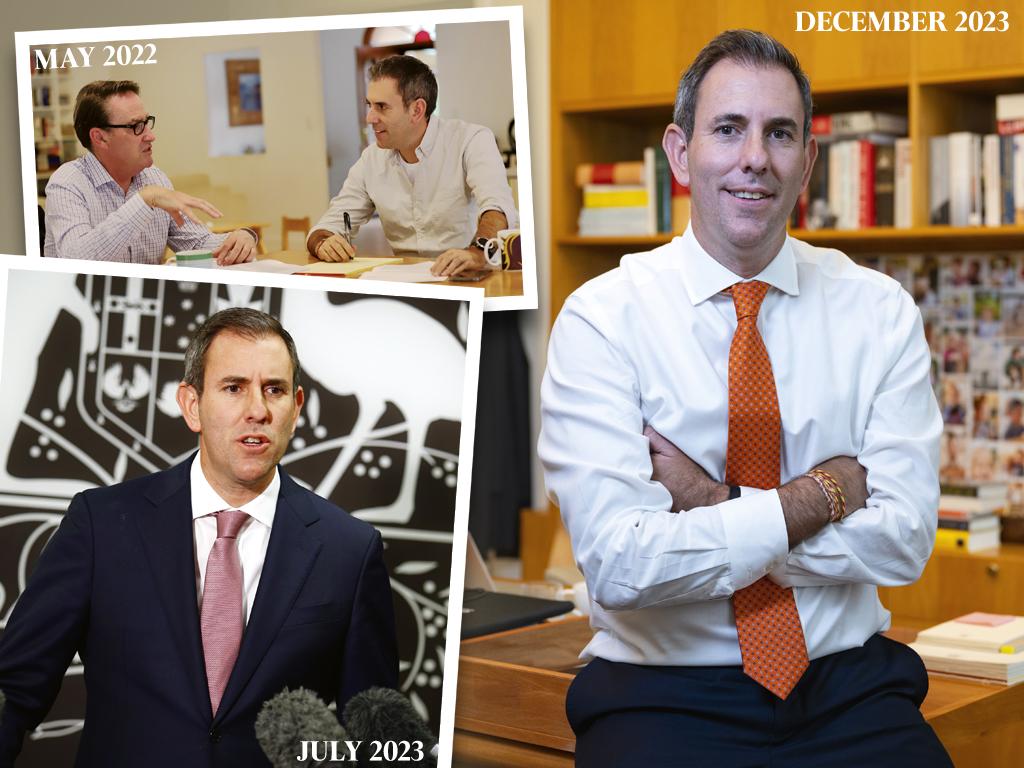

People are digging into their savings to staunch these negative influences. The recorded saving rate was a mere 1.1 per cent in the September quarter, the lowest rate since 2007. It had been 7 per cent last year. There is now very little left in the tank to provide further buffer for hard-pressed households. These were not the set of figures Treasurer Jim Chalmers would have wished for as an early Christmas present. An advocate of measuring what matters, he must surely acknowledge that real household disposable income, which includes the impact of the government’s cost-of-living measures such as energy and childcare subsidies, is a better measure of living standards than GDP.

But the Australian Bureau of Statistics figures clearly show these cost-of-living subsidies end up as additional government spending. The National Accounts note the “government sector increased spending on behalf of households. Indeed, government spending contributed 0.2 percentage points to GDP. State and federal government social benefit schemes for households, including the Energy Bill Relief Fund and expansion of the Child Care Subsidy, were the main contributors to the rise”.

This is the ongoing dilemma for Chalmers. While he likes to rattle off the list of relief measures the government has implemented – add in free TAFE, bulk-billing incentives, cheaper medicines and the like – there is a very real danger that any additional government spending will stall the transition to lower inflation and thereby increase the risk that interest rates will stay higher and for longer. It is the principal reason there were no further measures announced in the MYEFO.

The bigger picture here is that government measures to offset cost-of-living pressures must be paid for. The overpromising by governments to the public has built up expectations that living standards can be directly protected through government action. The combination of cheap money and historically high terms of trade assisted the federal government to maintain this fantasy for a while but, sadly, chickens have a habit of coming home to roost.

It was very significant that the National Accounts indicated the terms of trade – the ratio of export to import prices – had declined by 9 per cent over the year to the September quarter and that net exports made a negative contribution to GDP in the quarter. There is a possibility the good fortune of high terms of trade is coming to an end, an outcome that will place additional pressures on the federal and some state budgets.

The triumph Employment Minister Tony Burke exhibited as a result of the passing of the same job, same pay provisions of the Closing Loopholes legislation needs to be seen in this context. The stark reality is that the resources sector has underpinned much of the largesse handed out by federal governments over the past decade or more.

Absent the investment in the sector and the high prices the world has been prepared to pay for our commodities, managing budgets, both state and federal, would have been very different.

But by crimping labour hire arrangements that have been a means of ensuring a degree of cost competitiveness for a number of resource companies, including BHP, the direction of the effect is unambiguous – less mining activities, less investment in future projects. The resource industry is a global one and the major companies allocate capital on a competitive basis around the world.

Australia suddenly looks a lot less attractive, including for the new mining opportunities presented by the decarbonisation process and leading to us supposedly becoming a “renewable energy superpower”. It beggars belief that Jim Chalmers did not seek to intervene at least to water down these provisions, but it shows what a weak position he holds in cabinet.

This was similarly on view with the NDIS deal – some would call it a stitch-up. It’s all very well shifting expenditure out of the NDIS; but if the eligible non-participants receive the same level of assistance at a similar cost, the exercise is fiscally neutral, at best.

But it gets worse, because Chalmers was forced to extend the egregious GST deal that involves guaranteeing Western Australia a fixed share of its GST revenue – 70 per cent but rising to 75 per cent – as well as ensuring the other states are no worse off. The expensive deal was due to expire in the middle of the decade, but has now been extended until the end.

Add in the pledge for the federal government to lift its health funding contribution from 40 per cent to 45 per cent and it was obvious that Chalmers was completely rolled to get a deal across the line before Christmas.

Chalmers really needs to start telling the story that the fiscal salad days are over and real government spending needs to be returned to pre-pandemic levels. The tiny gains in real wages he has been highlighting don’t override the very real decline in average household living standards.

And without productivity growth – it fell by over 2 per cent in the year ending in the September quarter – we will need to get accustomed to much lower living standards. Just expect a fight in the meantime as various groups battle for their share of the shrinking pie.

December is a big month for economic news, with the release of the quarterly National Accounts and the Mid-year Economic and Fiscal Outlook.