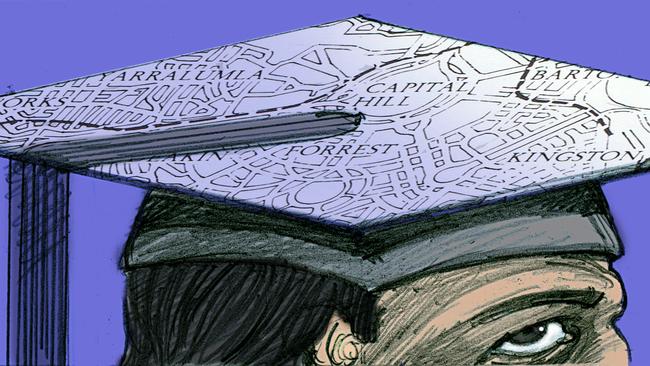

Free speech: It’s time for a higher education shake-up

It is with much humility that I announce my candidature for the forthcoming vacancy of chief executive of the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency.

TEQSA wields extraordinary power to decide what institution can call itself a university or college. It is responsible for enforcing the Higher Education Standards Framework, which includes requirements ranging from admissions and course design to facilities and infrastructure. This framework also requires that a university articulates “a commitment to and support for free intellectual inquiry in its academic endeavours”.

But in recent years TEQSA’s leadership has become a free-speech denier. It has repeatedly played down concerns from parliamentarians, academics, students and the broader public about the ability to express a wide array of opinion at our universities. Like practically every regulatory body, TEQSA has become captured by its sector and a certain left-wing, misnamed “progressive” perspective.

TEQSA chief executive Anthony McClaran will step down at the end of next month to take up the vice-chancellorship of St Mary’s University in London. The federal government must avoid simply appointing an individual from the sector, someone who will continue business as usual. It needs new leadership from outside the groupthink that epitomises higher education.

Across the English-speaking world, universities are becoming hotbeds of ideological extremists which reject the legitimacy of alternative perspectives. Across the past four years, in the Institute of Public Affairs’ Free Speech on Campus Audit, I have extensively catalogued how university policies and actions undermine freedom of expression. This has been acknowledged, even by its critics, as they point to the key report that first brought attention to free speech issues at universities.

Last year, the government released a review into free speech by former High Court chief justice Robert French. This report pointed to substantial issues within existing policies, including many previously raised by the IPA. It recommended universities adopt a model free-speech code, partly in the spirit of the University of Chicago. While some universities have acted, such as the University of Sydney, most have not. This is despite an IPA poll of university students last year finding that three in five students say they have been prevented from voicing their opinions on controversial issues by other students.

Nick Saunders, the chief commissioner of TEQSA, told Senate estimates last year that TEQSA would not be playing a “regulatory role, in the sense of imposing penalties” on universities that failed to adopt French’s code. Saunders also played down the possibility of future enforcement on the basis that he did not think freedom of expression on campus was an issue. All carrot and no stick (billions of dollars of public money without any responsibility) make for a pathetic lack of freedom of expression at our universities.

Last year, Peter Ridd was found to have had his freedom of speech impinged by James Cook University after it sacked him for criticising the quality of his colleagues’ work on the Great Barrier Reef. Ridd was awarded $1.2m after winning the unfair dismissal case. Despite the significance of the precedent-setting case, TEQSA has also yet to mention Ridd. TEQSA has also refused to issue a guidance note on freedom of expression or academic freedom, despite maintaining an extensive note on “diversity and equity”. This guidance typically focuses on every type of diversity other than diversity of viewpoint.

Free speech is not the only challenge facing our universities. They appear to be ferociously dependent on foreign funds, leading to substantial influence opportunities for the Chinese Communist Party. This is epitomised by the Confucius Centres and the slow reaction to thuggish pro-CCP students last year at Hong Kong democracy protests, particularly at the University of Queensland. There are also concerns that dependence on overseas students has lowered educational quality.

Gerd Schroder-Turk, an academic at Murdoch University, claimed universities, including his own, admitted international students who did not meet English language standards. “Admitting students who don’t have the right qualifications, or right prerequisites, or correct language capabilities, is setting them up for failure,” Schroder-Turk said. Academics are then pressured to pass these students, including many who stand accused of cheating, despite an inadequate quality of work.

Once again displaying the lack of tolerance for contrarian opinions, Schroder-Turk was sued by Murdoch University for daring to critique its approach. The response by TEQSA to these issues has been wholly inadequate.

Meanwhile, the “replication crisis” continues, with half of all published academic articles likely being unreplaceable and false. There are also concerns about students being sold degrees costing tens of thousands of dollars despite getting limited educational value or a high-paying job at the end. Many students simply drop out, leaving themselves with large debt and no degree to show for it.

The extent of red tape imposed by TEQSA makes it almost impossible to start up competitor universities that would bring real competition to the sector, thereby decreasing tuition costs and increasing educational quality.

The appointment of TEQSA’s next chief executive is a perfect opportunity for the Morrison government to give the Australian university sector a significant shake-up. And I am the person to do it.

Matthew Lesh is head of research at the Adam Smith Institute and an adjunct fellow at the Institute of Public Affairs.