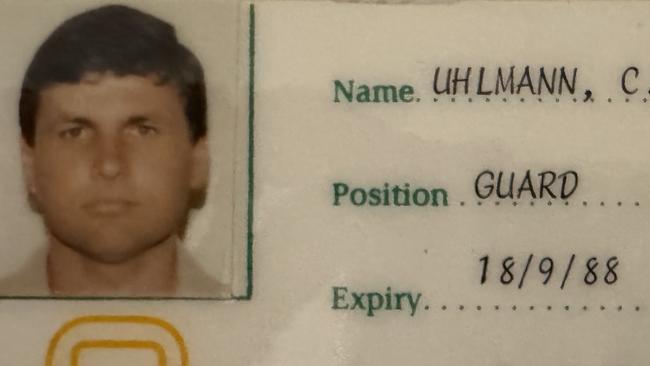

I had just finished a two-day security course that bought a licence I hoped would lead to some work. Nothing was guaranteed. The way the system worked was that new guards turned up at the office and lined up to be allocated one of the jobs scrawled on the whiteboard behind the main desk.

On my belt was the PR-24 side-handle baton and a 4D MagLite torch. I still have both. The 38cm long torch is made of aircraft-grade aluminium alloy and is powered by four D-cell batteries. Once filled with the big batteries, it weighs about a kilogram, making it part torch and mostly truncheon. The ex-cop had advised us that, if necessary, it was better to brain people with the torch than the baton because it would be easier to defend in court.

The line was a mix of unskilled workers, like me. That’s not entirely true. I had an associate diploma in religious studies, earned in three years studying to be a priest in my first, failed, career.

This was, in the immortal words of my junior rugby league coach, “as useless as tits on a bull” when it came to getting work in the 1980s, when the unemployment rate ranged from 8 per cent to 10 per cent nationally and was much higher the further down the food chain you swam.

I had spent two years as a storeman and packer, and was painfully aware that some very bad life decisions had put me at the bottom of that chain. The demographic in the security guard queue was as broad as Sydney’s western suburbs, with currency lads like me and those from Greek, Italian and Lebanese heritage predominating.

The guy behind me in the line tapped me on the shoulder.

“You’re new, mate, aren’t you?” he said.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Well, when you get to the front of the line, that guy is going to offer you a job at McDonald’s at Cabramatta.”

“Great, I need a job.”

“Don’t take it.”

“Why?”

“Viets, mate, they will stab you,” he said in a stage whisper that could be heard across the room. “They stabbed one of our guys there last week and now none of us will go there.”

This sparked an animated discussion in the line. Every ethnicity had a view. The consensus was that, as guards, they expected someone might try to punch them. If they hit the ground, it was considered poor form, but not unexpected, that someone might kick them.

But stabbing people was unacceptable.

“It’s un-Australian,” said a guy who might best be described as hailing from the Once Were Warriors end of Auckland.

I was offered, and declined, the job in Cabramatta. I don’t remember where I did work that night but the debate with the guards left a lifelong impression and it mirrored arguments I had read in a book called All for Australia, written by historian Geoffrey Blainey.

There Blainey, controversially, argued that immigration policy, particularly the rapid increase in Asian immigration, was being driven by politicians, academics and the media rather than public consensus.

Blainey believed the pace and scale of the change risked social cohesion. He argued that policymakers did not live in the “frontline suburbs” where the reality of the rapidly changing demographics landed. And there I was on the frontline, and some of those loudly echoing Blainey’s arguments were the most recent immigrants. This is something I have witnessed many times since.

I had direct experience with the wave of post-Vietnam War immigration to Australia. The novice master at our seminary, Father Tony King, had been instrumental in getting a group of Vietnamese sisters settled in an old Josephite convent at Granville. He was a great and good man but hailed from the old-school opinion that everyone understood English as long as you spoke it slowly and loudly enough. Today he would be considered a relic, but unlike those with no deeds to match their polished words, he settled about two dozen women from refugee camps in Southeast Asia.

The term boatpeople was coined in Australia when five Vietnamese asylum-seekers arrived in Darwin in April 1976 in a small fishing boat. Only about 2000 of the 90,000 Vietnamese who were resettled here came this way, but each illegal boat poured petrol on the immigration debate.

In the wake of Blainey’s book, opposition leader John Howard would walk into the minefield of immigration and social cohesion, with predictable consequences. He was branded a racist and it was among the reasons he lost the Liberal Party’s leadership before being resurrected in 1995.

As prime minister, he cracked down hard on illegal immigration and famously said the government would decide who came to the country and the manner in which they came.

Howard understood what activists ignored: that the Australian people would countenance one of the world’s largest per capita immigration programs only if they believed it was orderly. Illegal boat arrivals threatened to derail the peaceful settlement of millions. If you need evidence for this, look to Europe. Disorderly immigration driven by bad government decisions drove Brexit in Britain and the rise of Alternative for Germany. We have avoided wrenching social discord because of Howard’s hard line.

The nation should be grateful to Howard, Tony Abbott and Scott Morrison. Their unflinching stand against illegal immigration means the mass immigration program still enjoys broad public support. Being brutal on boat turnbacks and offshore processing is now bipartisan. No one should be more grateful for this than Labor, which is still quietly sending illegal immigrants to Nauru.

But it is past time to have a serious national conversation about the size and shape of Australia’s legal immigration program.

The numbers arriving have been much too high for too long. The nation’s capital stock is not growing in line with the population, and this has serious implications for productivity, living standards and long-term growth.

And it is not racist for a country to include social cohesion as one measure of who gets to live here.

If a politician cannot criticise the Chinese Communist Party for fear of losing Chinese Australian votes during an election, then we have a problem. If Jewish Australians fear for their safety, then we have a problem. If we have imported all the religious and ethnic disputes of the world, then we have a problem.

Recently, Anthony Albanese introduced the idea of “progressive patriotism”. He said it would be a guiding principle of his second term in government and it meant embracing national pride rooted in inclusivity, fairness and shared values.

What are those shared values? What does it mean to be an Australian in the 21st century? It’s time to call the line together for another chat.

It was 1988 and I was standing in line at the head office of Westgate Security in Parramatta, dressed in a green uniform I had picked from a rack of discarded clothes in the changing room.