The Convention is categorical: “The taking of hostages is prohibited.” Adding to the prohibition’s strength, the Convention defines hostage-taking, “which nothing can justify”, as one of the most serious offences against international humanitarian law, imposing on every signatory a duty to prevent it going unpunished.

Now Hamas has compounded the crimes it committed on October 7 by executing six hostages. Nor are those executions an isolated incident: as with al-Qa’ida and ISIS, seizing, abusing and murdering hostages has been part of Hamas’s strategy from the outset.

It would, however, be a mistake to view that strategy as resurrecting the “barbarous relic of ancient times”. It is, on the contrary, newer and grimmer – and grasping its novelty is crucial to understanding the nature of the conflict that is now under way.

In effect, the Nuremberg Tribunal erred grievously in characterising medieval Europe’s widespread use of hostages as “barbarous”. The primary role of hostages in those centuries was as surety for the performance of treaties. Unlike prisoners, hostages were given, not taken; they were almost invariably of high rank and, more often than not, directly related to the party proffering the guarantee.

Because of their rank and role, hostages were treated as “hospes”, that is, guests. Protected by the laws of chivalry, viewed as equals rather than as captives, hostages should not merely be allowed to travel freely “around the country visiting ladies and lords”; they were, a 16th century German rulebook specified, entitled to a regular supply of baths, prostitutes and new shoes.

There were, for sure, egregious breaches of the chivalric codes. But over the course of the 14th century, with its dozens of hostage agreements, there were only two recorded instances in which hostages were executed. And those executions were regarded both as appalling sins and as manifestly illegal.

Thus, already in 1588, Alberico Gentili, the father of international law, denounced the punishment of hostages, who had themselves committed no offence, as monstrous. Emer de Vattel was therefore echoing a widely held view when his vastly influential The Law of Nations (1758) described executing hostages as “an inhuman cruelty” and “a barbarism offensive to human nature”, contrary to natural law and the law of nations.

By then, however, reliance on hostages as guarantors had virtually disappeared, with its last major use being in 1748. It was the rise, in the Age of Revolutions, of brutally authoritarian regimes that brought a new, more fearsome development in hostage-taking: the capture and execution of unarmed civilians as a way of cowering populations into submission.

Pioneered by the French Revolution, that tactic was exalted by Lenin, whose “Hanging Order” of August 1918 directed the Bolsheviks in wheat-growing areas to publicly hang hundreds of hostages “so that for miles around the people can see, tremble and cry: they are killing and will go on killing”. Imitated by the Nazis, to horrendous effect, in retaliatory massacres at Lidice, Oradour-sur-Glane and the Fosse Ardeatine, that approach prompted the 1949 Convention’s prohibition against hostage-taking.

Unfortunately, the rise of Islamic terrorism marked the start of a third period in the history of hostage-taking that the new instruments of international law proved utterly incapable of quelling.

There had, even before then, been plenty of instances of hostages serving as bargaining chips. In 1958, for example, Fidel Castro’s rebels abducted 50 Americans and refused to release them until the US forced Fulgencio Batista’s regime into a ceasefire that would allow the rebels to rearm and regroup – which the US did, helping condemn Cubans to decades of misery.

What changed, however, was less the terrorists’ demands than the mechanisms they played off. While the Islamists were descending into a cult of death, ever-growing weight was being placed in the West on the innate value and equal dignity of human life. At the same time, the rise of the internet vastly enhanced terrorists’ access to, and ability to manipulate, public opinion – just as the new technologies were making public opinion increasingly influential in democratic politics.

The potential that created was at the heart of al-Qa’ida’s directive on kidnapping, which highlighted the scope to sow division in the target country by showcasing hostages’ desperate plight and demonstrating a readiness to mercilessly butcher them. The more obviously innocent the hostages and the grimmer the fate that awaited them, the more likely the strategy was to succeed; and the more open and democratic the target country, the greater was the harm it would inflict.

In short, much as Walter Benjamin famously observed, a step forward of civilisation spawned a step forward in barbarism: in this case, a barbarism that fed off the information revolution and used it to undermine societies that increasingly recognised, and were willing to debate, conflicting values, including the tragic choice between saving lives in the present and jeopardising even more lives in the future.

It is consequently unsurprising that the impacts have been felt with devastating force in Israel, an open society marked by a passionately involved citizenry and suffused with Judaism’s emphasis on the duty to protect human life. But the stark contrast between that society and the apocalyptic barbarism it confronts makes the tepid response in Australia to Hamas’s crime all the more disappointing.

There was, predictably, deadly silence from the Greens. Equally, the protesters, who incessantly claim the mantle of humanitarianism, were curiously nowhere to be seen. As for the government, its comment was limited to a single tweet that rightly condemned Hamas but said absolutely nothing about bringing the perpetrators to justice.

And while the tweet’s final sentence – “Every innocent life matters” – may have been well-intentioned, it unacceptably implied a moral equivalence between the cold-blooded murder of innocent hostages and the unintended deaths (caused largely by Hamas’s use of civilians as human shields) arising from the conflict in Gaza.

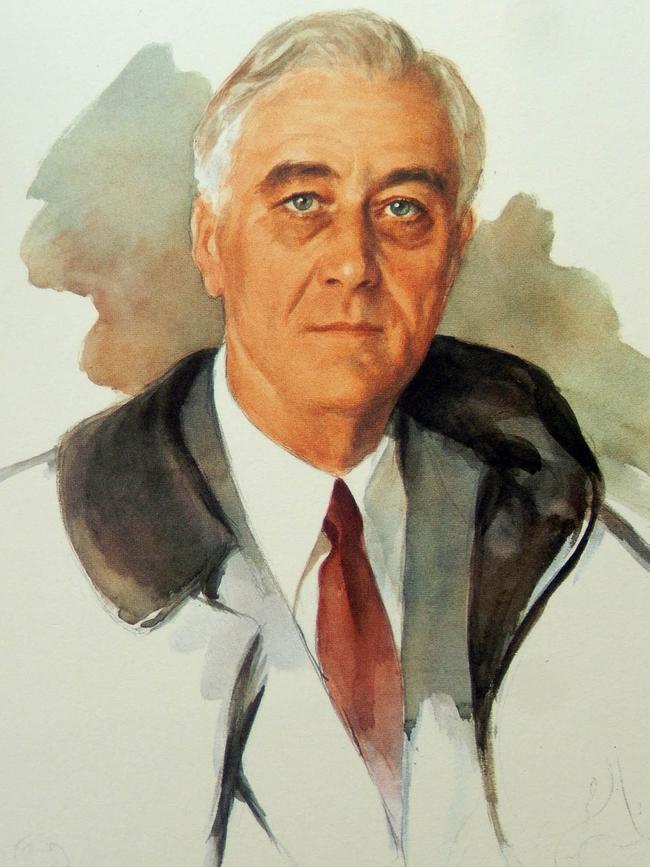

In October 1941, two months before the United States entered the war, president Franklin Delano Roosevelt said the Nazi practice of “executing innocent hostages revolts a world already inured to suffering and brutality”. Yes, the executions could terrorise. But they would “never bring peace”, instead “sowing the seeds of hatred which will one day bring fearful retribution”. Soon enough, the Nazis – “desperate men who know in their hearts they cannot win” – would have to feel the unrelenting force and unswerving determination of the “civilised peoples” they scorned.

Today, as Israel mourns its slaughtered hostages, the “civilised peoples” Roosevelt relied upon are weakened, divided, poorly led. Unless we can once again find that resolve to stare evil in the face, and destroy barbarism rather than repeatedly granting it reprieves, it is barbarism that will ultimately destroy us.

In 1947, the International Military Tribunal described the execution of hostages as “a barbarous relic of ancient times”. Bemoaning the lack of an explicit prohibition on hostage-taking, the Tribunal urged the world’s nations to act, which they did in the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949.