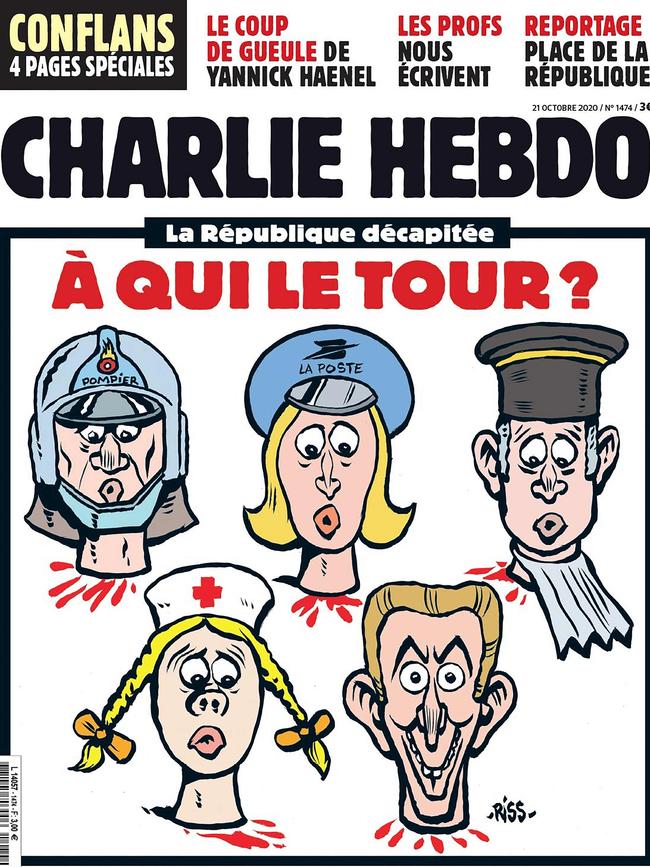

And five years after the attacks on Charlie Hebdo and on the Hypercacher supermarket, it is barbarism, not civilisation, that is steadily gaining ground.

To say that is not to underestimate the damage al-Qaeda and ISIS have suffered in recent years. Nor is it to ignore French President Emmanuel Macron’s firm reaction to the latest outrage.

“Now,” he said the other day, “fear will change sides: it is the terrorists who will no longer sleep well at night.”

But even the steeliest resolve cannot disguise the fact that Islamic fundamentalism, which provides the seedbed from which the terrorists sprang, is even more deeply entrenched in the West today than it was in 2015.

Nowhere are the trends clearer than in France itself. As Bernard Rougier — an eminent scholar of Islamic society who heads the Sorbonne’s Centre for Arab and Oriental Studies — shows in a book published earlier this year, “the territories conquered by Islamism” in France and its near neighbours have expanded steadily, while Islamism’s stranglehold over those territories has become stronger and more unshakeable.

Rougier does not present the Islamists as a monolithic bloc; rather, he highlights their diversity, as well as the intense rivalry between them. And he also shows that instead of weakening them, competition has made the Islamists stronger, eliminating the poorer performers and forcing the stronger to innovate constantly.

But while they compete ruthlessly, the Islamists share a common goal: to create, in the areas they control, “total societies” in which every contact between individual Muslims and the social world confirms their sense of apartness, heightens their perception of being besieged by an “impure” West and intensifies their commitment to the Islamist cause.

At the same time, by imposing a suffocating conformism, the Islamists seek — almost always successfully — to drive non-Muslims out of those areas, narrowing the cultural influences to which their inhabitants are exposed and creating an echo chamber in which Islamist rhetoric is constantly reaffirmed and magnified.

Macron has described the Islamists’ program as a form of separatism. But their objective is not to secede from the West; it is to destroy it and build a House of Islam on its smouldering remains.

Few things are more important to them, in the pursuit of that goal, than undermining the education system’s capacity to promote the values of freedom of thought and of expression.

The extent of their efforts has been chillingly highlighted by Jean-Pierre Obin, an enormously influential former Inspector-General of National Education, in a book that appeared merely weeks before Paty’s murder.

A lifelong man of the left who spent his youth helping the newly independent Algeria to rebuild, Obin is hardly a supporter of Marine Le Pen. But as he demonstrates in compelling detail, the Islamists and their fellow travellers have launched attack after attack on the school teachers who defend the “liberty, equality and fraternity” that have always been his lodestar. And instead of abating since 2015, the scale and virulence of those attacks has increased.

The crucial factor is that the Islamists have learned to imitate the tactics pioneered by #metoo and Black Lives Matter. Previously, their campaigns focused on generic issues, such as the ban on headscarfs. Now, helped by front organisations — such as the Collective Against Islamophobia in France (CCIF) — they target individual teachers, especially those who are Jewish, launching massive campaigns of demonisation on social media.

The CCIF-supported campaign that precipitated Paty’s murder should therefore have come as no surprise; nor should it be surprising that in the wake of that atrocity, so many teachers have disclosed instances in which they, too, felt threatened.

The effects Obin documents of the systematic intimidation are stark: over half the state school teachers in predominantly Muslim areas regularly self-censor the curriculum, glossing over the required topics — such as the Holocaust, the conflict in the Middle East, the right to freedom of religion and of expression and the importance of equality between the sexes — which most frequently trigger noisy protests by Muslim students and carefully orchestrated allegations of Islamophobia from their parents.

Meanwhile, in the rapidly growing Islamic schools — which, as a condition of their generous taxpayer funding, should be following the national curriculum — teaching of those topics is often distorted beyond recognition.

The results are apparent in a large-scale survey, conducted three months ago, of France’s young Muslims, which found that nearly half regard upholding Islamic values as more important than preserving freedom of religion, thought and expression. And with more than a quarter refusing to condemn the 2015 terror attacks, the prospects for a peaceful future seem all too bleak.

No one believes these problems lend themselves to easy solutions. What is clear, however, is that the standard response of governments, including our own — which involves reaching out to Islamic leaders after each terror attack, while vastly increasing spending on community programs in areas with significant Muslim populations — is deeply counterproductive.

Rougier’s findings confirm the conclusions of French socialist Malek Boutih’s official report on the 2015 terrorist attacks: rather than undermine the Islamists’ position, the torrents of poorly monitored public funding have gifted them a host of readily captured revenue sources, thus boosting their organisational capabilities.

As for the prominence governments accord to religious leaders, it has entrenched Islam’s role as the community’s point of reference, making it even easier and more rewarding for disciplined Islamists to displace their generally ineffectual moderate rivals.

With the grim reality of last Friday’s murder sinking in, Macron appears to have recognised these policy failures, relying instead on tough-minded deterrence as the primary response. Claiming there will be no more “trembling hands”, his government seems set to ban the Anti-Islamophobia Collective, along with up to 50 other Islamic organisations and “charities”, close several mosques (including one whose iman welcomed the beheading of “a blasphemer”), deport a host of Islamists and strictly monitor Islamic schools.

What will come of those commitments remains to be seen. But we, too, need to reconsider our approach before more grisly attacks soil our streets. After all, from Sydney’s Lakemba to Melbourne’s Broadmeadows, the Islamists are quietly building up positions every bit as impregnable as those they now hold in Paris’s Aubervilliers and Brussels’ Molenbeek.

Faced with that threat, the Peter Pan strategy — close your eyes and wish really hard — promises one thing and one thing only: tomorrow, we will all be Samuel Paty.

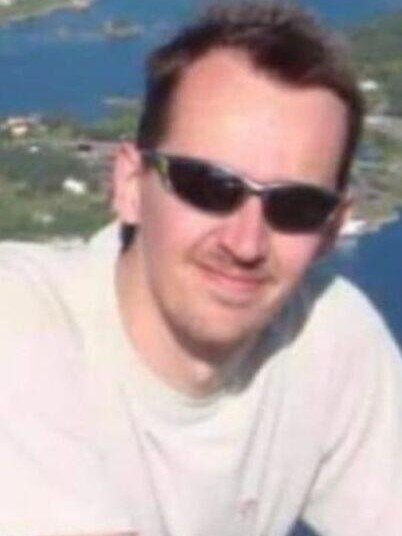

Samuel Paty, the French schoolteacher decapitated last Friday for showing his students a caricature of the Prophet Mohammed, did not lose his life in a clash of civilisations; he lost it in a clash between civilisation and barbarism.