That is the unavoidable verdict on the Iraq War, after twenty years. In an essay published the day the war started, I wrote that, while the moral and legal cases for going to war were moot, the war would come to seem a strategic blunder, to be a “stupid” move by Washington, should it turn from the swift removal of Saddam (which occurred) into a long and bloody urban guerrilla war.

It gives me little satisfaction to have been vindicated. And yet, when net assessments are made, looking back, it is too easy to make the mistake of comparing the way things are now to what they were, rather than seeking to conceive how they might have been had the war not taken place, or had it been managed more prudently. For the sake of realism, we must do the latter.

In his masterful survey of 21st century terrorist insurgency, asymmetric warfare and destabilising technologies, Terror and Consent, Philip Bobbitt observed that: “Parmenides’ Fallacy occurs when a decider contrasts a proposed option with the present context rather than with other possible contexts that will eventuate if other options are exercised; things change and so indefinitely extending the present is never a realistic option.”

It was Rolf Ekeus, former head of UNSCOM, the United Nations commission tasked with monitoring Saddam’s compliance as regards Weapons of Mass Destruction, who stated that to argue that the invasion of Iraq was about finding and seizing Saddam’s existing stocks of WMD trivialised the issues that were at stake.

Unless one holds that Saddam’s acquisition of WMD would have been of no consequence, the alternative to invasion was a prolonged American presence in the Persian Gulf to hold the threat of armed intervention over Saddam’s head and the perpetuation of sanctions designed to thwart his plain intention to acquire such weapons. The costs of those sanctions were being passed on to ordinary Iraqis by Saddam and thousands of Iraqi children were dying. His was a murderous regime, as Kanan Makiya showed in Republic of Fear and Cruelty and Silence.

Saddam was neither acquiescent nor penitent. The former head of the Iraq Survey Group, in testimony before the US Congress, reported that Iraq’s illegal military procurement budget increased one hundred-fold from 1996 to 2003 – the seven years leading up to the war. He testified that it was indisputable that Saddam intended to renew his development of WMD as soon as he could get the UN sanctions lifted.

The consensus of the best informed and most soberminded experts was that regime change alone could head off Saddam’s WMD ambitions, whether or not Iraq possessed such weapons before the intervention. But this is not the narrative propagated by those who opposed the war as a matter of principle, or those who deplored it given the failure to find WMD in Iraq, or those appalled by the prolonged and costly guerrilla war which ensued.

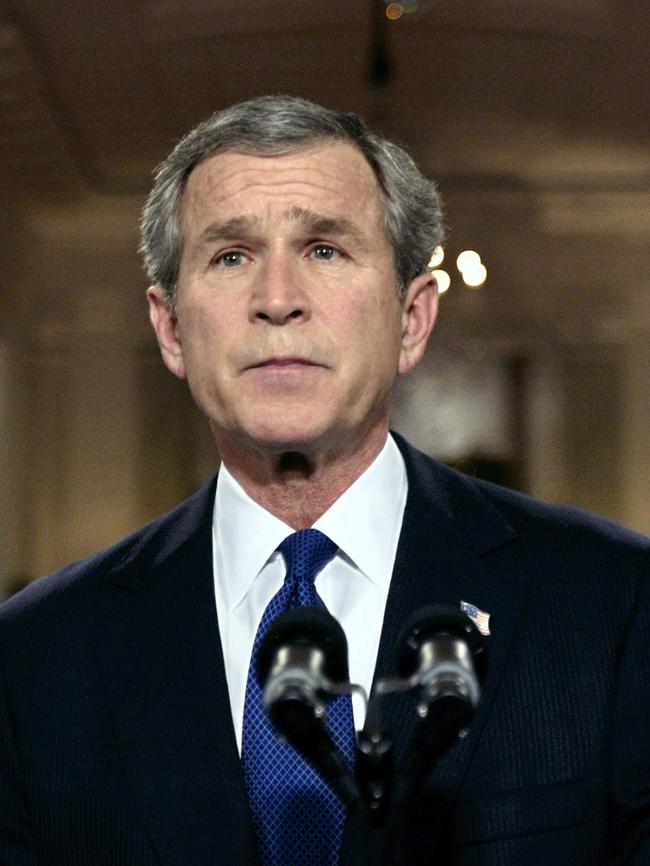

The confounding thing is that the case for war was so badly made in 2002-03. This was compounded by the abject failure by Donald Rumsfeld and others reporting to President George W Bush to think through with any degree of seriousness how they would reconstitute governance in Iraq after overthrowing Saddam.

If you are going to fight a war of choice you owe it to yourselves, your soldiers and your citizens to make a solid case for doing so and then planning meticulously how to achieve the goals envisaged effectively and efficiently.

When Benjamin Wittes wrote Law and the Long War: The Future of Justice in the Age of Terror, in 2008, the long war he envisaged was against radical Islam. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, for all their bungling and exorbitant costs, went far towards quelling and discrediting radical Islam. But the world turns. We are now engaged in what Rush Doshi, in his survey of the scene, The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order, depicted as the real long war of the epoch.

We long got China wrong. We’re correcting course. Our current debates over the Quad, AUKUS, nuclear submarines and sovereignty all circle around this. The lesson to learn from the Iraq War is not that the United States is a rogue power in decline, but that effective, democratic grand strategy demands very high levels of thinking, responsibility and economy. How not to do those things is the major lesson from the Iraq War.

Paul Monk is a Fellow of the Institute for Law and Strategy and the author of Dictators and Dangerous Ideas.

The policy disarray in Washington, on the eve of the invasion of Iraq, in early 2003, was disquieting. The stretching of intelligence to justify a war of choice was pernicious. The patent lack of planning for what was supposed to occur after the overthrow of the tyrant Saddam Hussein was reckless. The occupation was bungled and the attempt at nation building a failure.