The Conservatives saw their vote plummet from 44 per cent to 24 per cent in just five years. But behind the facade of that result lurked the toxic issue of immigration and multiculturalism. It’s what the Americans like to call a “third rail” issue.

Across the English Channel, the French election was also a huge warning for Australia. In that election, the anti-immigration party of Marine Le Pen won more votes than any other political party although the parties of the centre and the left by collaborating each won more seats. Le Pen’s party won 37.3 per cent of the vote while the coalition of the left won 26.9 per cent. This was a huge vote against immigration and multiculturalism.

This same trend has been seen over the past year in the Netherlands and Italy and more importantly helps explain the Trump phenomenon in the United States. For a long time, commentators argued this rise in support for these hitherto fringe political movements was caused by globalisation: the loss of manufacturing jobs to China, the decline in living standards in traditional industrial towns, and so on.

There may be some truth in this. After all, centre-left and centre-right governments believe heavy manufacturing should be closed down because of the CO2 emissions it generates. Better to transfer those emissions to China and India. A lot of punters may think that policy is not just damaging to them but intellectually absurd. But still, that isn’t the main reason many people are shifting away from traditional parties.

The fundamental cause of this drift away from traditional political parties of the centre left and centre right is the way immigration and multiculturalism have been handled. It would be a mistake to think that in Britain, France, the Netherlands, the US and Italy the public are opposed to immigration. It’s not that simple. And it’s not that they object to people because of their colour. Immigration is not so much the issue as two aspects of it. The first is unregulated immigration. Tens of thousands of migrants have been pouring into Europe and America without approval, normally courtesy of people-smugglers.

Unregulated immigration is deeply unpopular. And the second issue is those migrants who fail to integrate into society. Multiracialism is one thing but the term multiculturalism, which we all praise, denies the existence of cultural norms that bind a society together. That is resented and creates tensions and divisions.

In France and the UK, some migrants have congregated very heavily in particular suburbs of major cities, turning those suburbs into what appears to more traditional people little more than foreign enclaves.

The people within those enclaves are often alienated from the rest of society by virtue of their physical isolation. The enclaves have their own schools, religious institutions, shops and so on. In recent elections, these concentrations of migrants have had an alarming effect on electoral outcomes.

In the recent UK election, in constituencies where at least 40 per cent of people are Muslims, the Labour vote actually declined from the 2019 election by nearly 34 per cent! In constituencies where Muslims made up between 10 and 20 per cent of the vote, Labour’s vote fell by 6.8 per cent, whereas in constituencies where Muslims accounted for less than 10 per cent of the electorate, Labour increased its vote by an average of 3 per cent. In a general election that was a triumph for the Labour Party it nevertheless lost five seats to Muslim activist independents.

This recent practice of migrants or the descendants of migrants of a particular religious persuasion voting en bloc – in this case on the issue of the Hamas-induced war in Gaza – has alarmed not just the Labour Party but the broader British population. But for immigration and multiculturalism to be embraced, and for a country successfully to hold together as an entity, there have to be some binding principles and attitudes that define the nation. Without that, the nation will atomise.

As British philosopher Sir Roger Scruton wrote: “We, like everyone else, depend upon a shared culture for our security, our prosperity and our freedom … we can welcome immigrants only if we welcome them into our culture, and not beside or against it.” Three days after the election, former Labour prime minister Tony Blair gave some stark advice to the new government. He said new Prime Minister Keir Starmer “needs a plan to control immigration” and made the very simple point: “If we don’t have rules, we get prejudices.” That’s exactly right.

In the US this issue is also very potent and one of the driving forces of former president Donald Trump’s popularity. It is claimed that some 10 million illegal migrants have entered the US since President Joe Biden was elected. That figure may be a bit of an exaggeration, but still, the problem of illegals pouring over the Mexican border is huge.

Within the US multiculturalism is embraced and accepted. In the main. But like anything, it can be taken too far. To use it as a tool by specific ethnic groups to denigrate the nation that has welcomed them, to pour scorn on its history and to appear supportive of its adversaries is politically inflammatory. It is also disrespectful of the country that has welcomed these people to its shores.

So what about our own country? We have to be careful. Senator Payman was elected on a Labor Party ticket and has resigned from that party over the issue of a foreign war in which Australia is not involved. If our politics is going to descend into this kind of ethnic conflict, then it’s going to be hard to keep our country together.

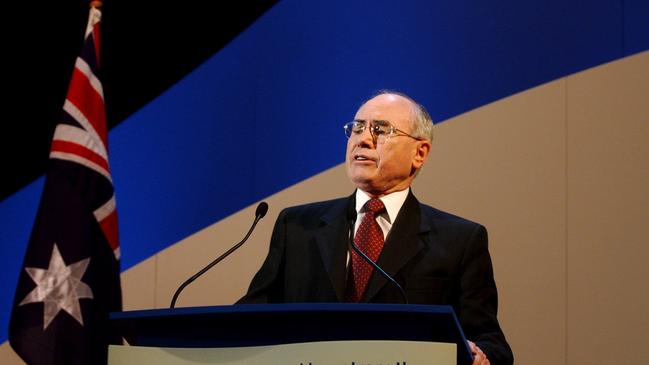

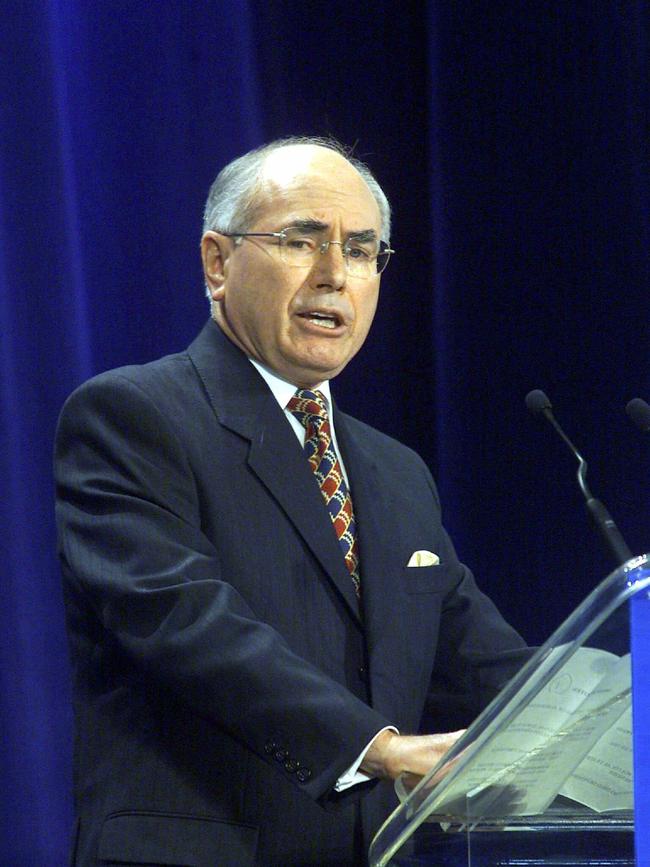

But don’t worry, the punters won’t tolerate that and will start voting with greater enthusiasm for fringe political movements if our two mainstream parties don’t just control immigration – the Howard government explained all that many years ago – but make sure there are core principles that hold our country together. We cannot afford to allow a hugely successful country to atomise.

More Coverage

For a long time, commentators argued this rise in support for these hitherto fringe political movements was caused by globalisation:

For a long time, commentators argued this rise in support for these hitherto fringe political movements was caused by globalisation:

Buried away in the British election results is a huge warning for Australia, made all the more relevant by the Senator Fatima Payman saga. On the face of it, the election was a triumph for British Labour, of course. It won over 65 per cent of the seats in the House of Commons. But in electoral terms, it won only 34 per cent of the vote.