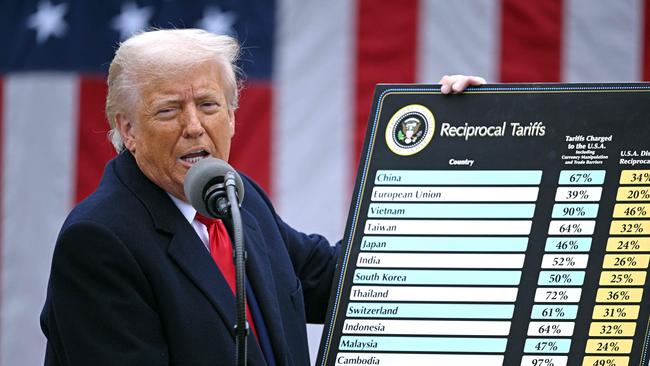

It would be difficult to imagine a more protectionist start to a presidency. Trump’s so-called ‘reciprocal tariffs’ started at 10 per cent and escalated for individual countries based not on their own trade policies but on their trade surpluses with the United States – a bizarre economic proposition.

Yet something remarkable has emerged from the ensuing chaos.

The political left, previously suspicious of free trade, has suddenly discovered its virtues. Liberal Americans who once marched against trade deals now cite David Ricardo. European leaders who have maintained protected agricultural markets for decades suddenly proclaim themselves champions of open commerce.

This extraordinary reversal represents perhaps the most astonishing ideological about-face I have witnessed.

I was a school student in West Germany when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. I still remember the sense of euphoria when the Iron Curtain lifted. Where previously there had been a dangerous military confrontation, trade and exchange now blossomed. Economic activity replaced armed standoff.

My own life story has been shaped by the globalisation that followed. I went from Germany to Australia for doctoral studies, then worked in London, moved to Sydney and eventually ended up in New Zealand.

This country-hopping felt entirely natural in an increasingly borderless world. To me, the freedom to study, work and live across multiple continents was globalisation on a personal level. Not just goods and services crossing borders, but people and ideas too.

During those formative years studying economics in the 1990s and early 2000s, the case for free trade seemed self-evident. Francis Fukuyama had declared ‘the end of history’. Thomas Friedman published The World is Flat. Martin Wolf explained Why Globalisation Works in his 2004 book. The intellectual consensus around globalisation appeared unassailable.

That is why I found it so puzzling when left-wing students at my university railed against trade liberalisation. These critics – outside the economics department, of course – denounced free trade as corporate exploitation and a race to the bottom.

Meanwhile, church groups insisted that only ‘fair trade’ could deliver justice, dismissing the overwhelming evidence that open markets were lifting millions from poverty faster than any development program ever devised.

The intellectual leaders of this movement – Naomi Klein, Joseph Stiglitz, Noam Chomsky, the ATTAC organisation – gained traction. Their arguments culminated in the famous ‘Battle of Seattle’ in 1999, when protesters shut down the World Trade Organisation conference, and violent demonstrations at subsequent G7 summits.

What made these protests so frustrating was that they attacked a principle whose intellectual foundation had been firmly established more than two centuries earlier.

From Adam Smith to David Ricardo, from Frédéric Bastiat to Richard Cobden, the case for free trade rests on rock-solid economic logic. When two parties trade, whether across a street or across an ocean, they do so because both benefit. Each values what they receive more highly than what they give in exchange.

This mutual advantage underpins the entire theory of the division of labour. Trade rewards specialisation. That fuels productivity. It is the foundation of our prosperity. For an economist, to argue against free trade is like arguing that the world is flat or that the sun orbits the earth.

Yet here we are in 2025, watching former free-market champions on the political right adopt the very same fallacies once championed by the left. The rhetorical parallels are uncanny: protecting workers, preserving national industries, preventing exploitation by foreigners.

One of the most striking ironies is that the political right now rails against those evil ‘globalists’ and the World Economic Forum.

Just two decades ago, the annual Davos gathering needed police protection from left-wing protesters.

‘Davos Man’ and globalisation were the bête noire of the political left. Now it is exactly the other way around, with right-wing populists seeing globalist conspiracies at every turn.

I sometimes wonder whether these recent converts truly believe their new antitrade rhetoric or if they are simply following the latest intellectual fashion served up by their political heroes. Political tribalism is a powerful force.

A recent study by the Polarisation Research Lab provides evidence of this ideological flip. It shows that, until 2024, US liberals and conservatives had similar levels of support for free trade. After Trump’s victory and tariff announcements, the picture changed dramatically. Support among liberals doubled to over 40 per cent, while conservative support plummeted to just 13 per cent.

Meanwhile, throughout this strange reversal, classical liberals and free-market economists like me have maintained consistent positions. We defended free trade when the left attacked it in the 1990s. We defend it still as the right abandons it in the 2020s.

Our arguments have not changed because economic principles do not bow to political fashion. Free trade remains the greatest poverty-reduction mechanism ever devised, a force for peace between nations and an essential element of human freedom and dignity.

What has changed is the political coalitions surrounding these principles. And herein lies the potential silver lining to Trump’s first 100 days.

By pushing protectionism to extremes, Trump has inadvertently broadened the coalition supporting free trade. He has reminded liberals why open markets matter. He has forced the European Union to confront its own protectionist contradictions. He has even pushed China to embrace market principles – rhetorically, at least.

Perhaps this moment offers an opportunity to build a broader, more durable support base for free trade.

Maybe we can engage those on the left who have rediscovered these principles, while hoping the right eventually returns to economic reason.

In Goethe’s masterpiece Faust, Mephistopheles tells us: ‘I am part of that power which eternally wills evil and eternally works good.’

Donald Trump may well be the Mephistopheles of trade policy – a figure whose protectionist impulses have paradoxically strengthened the intellectual case for free exchange. Through their negative effects, his tariffs may ultimately prove more damaging to protectionism than to trade itself.

That would be a fitting irony for the first 100 days of Trump’s second term.

Dr Oliver Hartwich is the Executive Director of The New Zealand Initiative

One hundred days into Donald Trump’s second presidency, his economic nationalism has produced an unexpected consequence. The man who campaigned on ‘America First’ and delivered sweeping tariffs within weeks of retaking office has become an unlikely champion of free trade – by forcing his opponents to defend it.