Historical context? Journos’ open letter is an exercise in historical distortion

As a prime example of the “important contextual references” which “it is the media’s responsibility” to provide, the letter cited “the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their native lands in 1948 to make way for the state of Israel”.

That now endlessly repeated claim clearly implies that the founders of the state of Israel deliberately provoked the refugee outflow. But far from accurately portraying the historical context, it grotesquely misrepresents, in a manner exemplary of the letter’s “one-sideism”, a complex reality.

Thus, when a majority of the UN General Assembly endorsed a partition of the British mandatory territory of Palestine on November 29, 1947, the major Zionist forces reluctantly accepted the proposed plan, despite its draconian conditions.

But the Arab states not only rejected the plan; they launched what the Arab League described as “a war of extermination” whose aim was to “erase (Palestine’s Jewish population) from the face of the earth”.

Nor did the fighting give any reason to doubt that was the Arabs’ goal.

At least until late May 1948, Jewish prisoners were invariably slaughtered. In one instance, 77 Jewish civilians were burned alive after a medical convey was captured; in another, soldiers who had surrendered were castrated before being shot; in yet another, death came by public decapitation.

And even after the Arab armies declared that they would abide by the Geneva Convention, Jewish prisoners were regularly murdered on the spot.

While those atrocities continued a long-standing pattern of barbarism, they also reflected the conviction that unrestrained terror would “push the Jews into the sea”, as Izzedin Shawa, who represented the Arab High Committee, put it.

A crucial element of that strategy was to use civilian militias in the territory’s 450 Arab villages to ambush, encircle and destroy Jewish forces, as they did in the conflict’s first three months.

It was to reduce that risk that the Haganah – the predecessor of the Israel Defence Force – adopted the “Dalet plan” in March 1948, which ordered the evacuation of those “hostile” Arab villages, notably in the surrounds of Jerusalem, that posed a direct threat of encirclement.

The implementation of its criteria for clearing villages was inevitably imperfect, but the Dalet plan neither sought nor was the primary cause of the massive outflow of Arab refugees, which was well under way before it came into effect.

Nor was the scale of the outflow much influenced by the massacres committed by Irgun and Lehi – small Jewish militias that had broken away from the Haganah – which did not loom large in a prolonged, extremely violent, conflict that also displaced a high proportion of the Jewish population.

Rather, three factors were mainly involved. First, the Muslim authorities, led by the rector of Cairo’s Al Azhar Mosque, instructed the faithful to “temporarily leave the territory, so that our warriors can freely undertake their task of extermination”.

Second, believing that the war would be short-lived and that they could soon return without having to incur its risks, the Arab elites fled immediately, leaving the Arab population leaderless, disoriented and demoralised, especially once the Jewish forces gained the upper hand.

Third and last, as Benny Morris, a harsh critic of Israel, stresses in his widely cited study of the Palestinian exodus, “knowing what the Arabs had done to the Jews, the Arabs were terrified the Jews would, once they could, do it to them”.

Seen in that perspective, the exodus was little different from the fear-ridden flights of civilians that have always accompanied wars, including the vast population movements associated with the collapse of the Ottoman, Habsburg and Russian empires, the capitulation of Nazi Germany and the dismemberment of Yugoslavia.

And it pales compared to the suffering caused (at almost the same time as the war in Palestine) by the partition of British India – a blood-soaked catastrophe, displacing tens of millions of people, which the distinguished Indian judge and essayist G.D. Khosla recalled as “an event of unprecedented horror”.

But while the mass outflow was not unusual, its sequel was. In the other major cases, refugees were ultimately absorbed into their country of refuge.

By 1960, the 12 million ethnic Germans who, after centuries of settlement, fled or were forcibly deported at the end of World War II from central and eastern Europe had fully merged into West German society. Equally, the illiterate Hindus who flooded, entirely destitute, into East Punjab underpinned the Indian Punjab’s momentous transformation into the country’s breadbasket.

And the 750,000 Jews – a number slightly greater than that of Palestinian refugees – brutally expelled (and comprehensively expropriated) during and after 1947 by the Arab states eventually became an integral part of Israeli society.

Moreover, in none of those instances, or even of the vast population transfers between Turkey, Greece and Bulgaria, were there durable revanchist movements, much less any expectation of a “right of return”.

Not so in respect of the Palestinian refugees, who became permanently homeless. That was, at least in part, the UN’s fault.

As many studies have shown, a central element in the remarkable success of the Turkish-Greek population exchange of 1922-23 was the tying of all international resettlement assistance to the unfettered integration of refugees into the country of refuge. The Refugee Settlement Commission (1923-1930) was therefore explicitly based on the principle that help would never suffice unless refugees were “forced to prosper”.

Operating under a strictly time-limited mandate, the RSC depended entirely on loans that could be repaid only if the refugees, rather than devoting their lives to terrorism, were productively employed.

But instead of heeding that precedent, the UN established the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, a bloated, grant-funded bureaucracy whose survival depended on endlessly perpetuating the Palestinians’ “refugee” status, regardless of the fact that they and their parents were actually living in the land of their birth.

Yet the UN was merely doing the bidding of the Arab states, which increasingly relied on the issue of Palestine to convert popular anger at their abject failures into rage against Israel and the West. Terminally corrupt, manifestly incapable of economic and social development, the Arab kleptocracies elevated Jew-hatred into the opium of the people – and empowered the Islamist fanaticism that has wreaked so much harm worldwide.

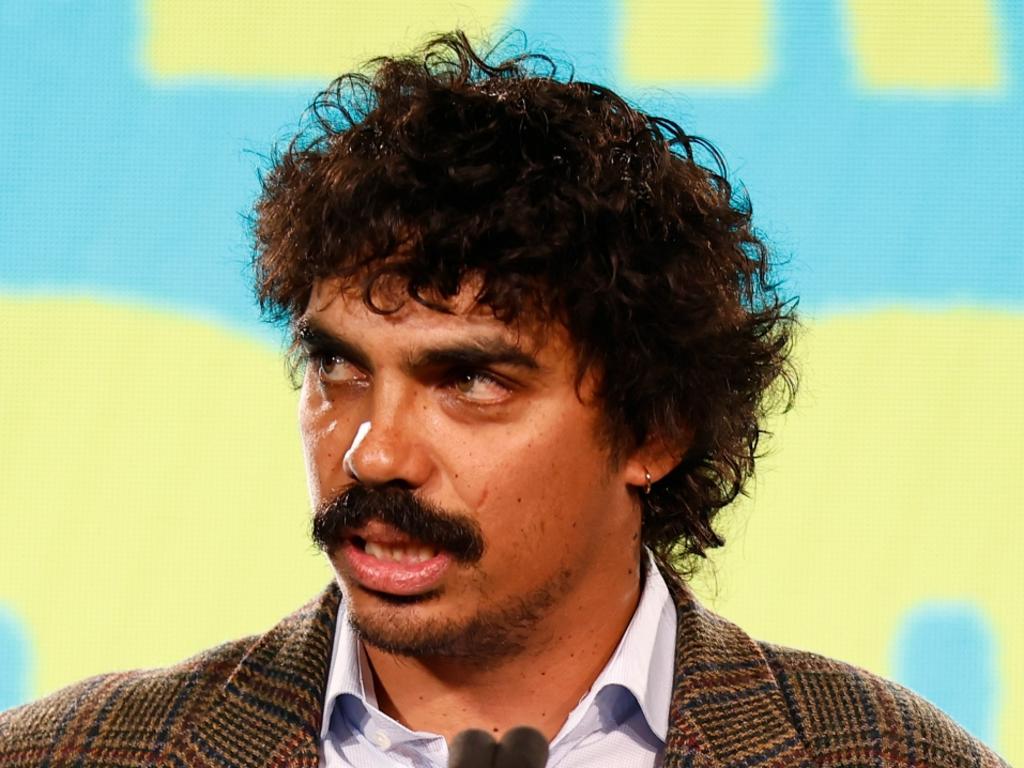

Of course, none of that matters to the open letter’s signatories. Flaunting their keffiyehs, these armchair warriors, who are far removed from any risk of being butchered by terrorists, have convinced themselves that they are the guardians of the truth, and that anyone who calls out their grievous errors is in bad faith. To say they are one-eyed would be wrong; drenched in bias, ignorance and self-righteousness, they are no-eyed. The tragedy is that anyone would follow them in their blindness.

Late last week, a “Letter from journalists to Australian media outlets” urged newsrooms to “adhere to truth” rather than “both-sidesism”, including by “providing historical context” in reporting on the Middle East.