Treaties are, of course, hardly a recent development, any more than is their use for territorial expansion. Centuries ago, Cicero listed them in On Duties (De Officiis) as one of the major ways in which territory could be legitimately acquired. But even then, they were far from uncontentious, with Polybius exemplifying their shortcomings by the treaties between Rome and Carthage, whose ambiguities stoked the very wars they were intended to avoid.

Nonetheless, the deeply ingrained legalism of medieval and early modern Europe helped place treaties at the heart of relations between princes. Moreover, the Reformation heightened their importance during the Age of Exploration, as it swept away the papal bulls that had previously served to legitimate overseas conquests.

That period, which broadly went from the 16th century to the end of the 18th century, saw a fundamental transformation in the status of treaties. At its outset, the distinction between treaties and contracts was extremely blurred. Made in the name of their signatories, treaties could be entered into by subordinates, such as feudal lords, as well as by monarchs.

That changed, however, with the emergence of what became the modern state, and of the concept of sovereignty with it.

Just as in republican Rome a treaty required Senate approval, so, beginning with Henry V’s treaty with Sigismund in 1413, treaties increasingly invoked the authority of the nation, bestowed not solely by the monarch but through ratification by parliaments or estates. Hugo Grotius, writing in 1625, could therefore define a treaty as “a contract of sovereigns”, excluding agreements reached by or with sub-national entities.

Additionally, and importantly, the production of compilations of treaties – starting with Jacques Bernard’s Compendium in 1700 – encouraged their standardisation, aided by the acceptance of French as the lingua franca of diplomacy. As European diplomats came to share a conceptual framework, the groundwork was laid for the proliferation of interstate treaties in the 19th century.

Unfortunately, the factors that facilitated treaty-making within the West were irrelevant to relations between European colonisers and indigenous peoples. Grotius had authoritatively stated that “the right of making alliances is common to all men”; but that did nothing to ensure the colonial treaties were understood by those who signed them – or that their translations reflected a common appreciation of the treaties’ implications.

Nor was their continuing legal significance apparent, all the more so as the chieftains invariably abdicated any claim to sovereignty, undermining the treaties’ standing.

It is therefore unsurprising that John Marshall, Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court, could, in the landmark case of Cherokee Nation v Georgia (1831), call them an anomaly, “marked by peculiar distinctions which exist nowhere else”. While accepting that the Cherokees were “a distinct political society”, he found that they were, in legal terms, no more than “a domestic dependent nation”, whose treaties were “completely under the sovereignty and dominion of the United States”.

Chief Justice James Pendergast of New Zealand echoed that view when he ruled in 1877 that “the pact known as the ‘Treaty of Waitangi’ must be regarded as a simple nullity”.

And Labour prime minister Michael Savage confirmed it in 1939, stating that despite frequent references to the treaty as New Zealand’s Magna Carta, “the Treaty of Waitangi creates no rights cognisable in a court of law”. But in this area, like many others, the 1960s turned the world upside down. Indigenous activism exploded; so did judicial activism; and left-leaning governments followed suit.

In 1966, a powerful dissent by Justice (later Chief Justice) John Cartwright of the Supreme Court of Canada heralded the change, not only by breathing new life into old treaties but also by completely ignoring the traditional rules, set down in international law, of treaty interpretation.

Central to this new approach was the rediscovery of Sir Edward Coke’s concept of “the Honour of the Crown”, which the great Elizabethan jurist had articulated in 1613. Almost entirely forgotten since then, it imposed on the Crown the highest standard of conduct, as assessed by the court, even if the conduct it prescribed went well beyond what was convenient, required by law or reasonably likely in the circumstances.

Gradually establishing itself after Cartwright’s 1966 dissent as the dominant normative standard in Canadian Indian treaty cases, the “Honour of the Crown” entered the Waitangi Treaty’s interpretation as judge-made law in 1987. But it was only some years after the Treaty of Waitangi Act of 1985, which empowered the until then largely toothless Waitangi Tribunal to investigate claims dating back to 1840, that the consequences of imposing a much higher standard on the Crown’s relation to indigenous people than on its relation to other citizens became fully apparent.

As historian Ruth Ross had noted in 1972, only so much burden could be borne by a treaty that was “hastily drawn up, ambiguous and contradictory in content, chaotic in its execution”. But the Tribunal was imbued with its mission of correcting historical wrongs.

It therefore decided to hold the Crown to the highest conceivable standard of conduct and – showing scant regard for causation – considered it solely responsible for the result of any shortcomings from that standard. It also determined that in defining the ideal conduct, the many ambiguities and inconsistencies in the Treaty were to be resolved to the claimants’ benefit, thus breaching the longstanding doctrine that treaties should be interpreted neutrally as between the parties.

And when the documentary evidence (typically amounting to many metres of shelf space) didn’t suit the resulting narrative, it felt free to dismiss it, as in Muriwhenua Land (1997), for “presenting only a European point of view”. Those “self-serving” European explanations were, it said, to be replaced by a “Maori world-view”, which the Tribunal implausibly assumed had remained unchanged for centuries.

Finally, having thus proven that bad history, like bad currency, drives out good, it would construct, as the basis for determining the compensation that was due, a shining past-that-could-have-been-had-the-government-acted-properly, in a fiction rightly derided by historian Bill Oliver as a “retrospective utopia”.

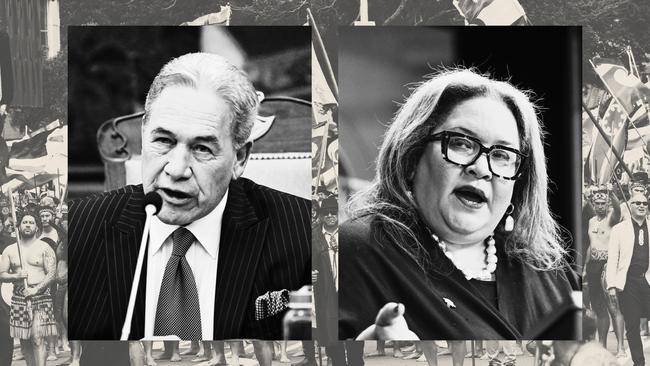

However, the greatest harm the Treaty has caused does not lie in the sweeping rights and taxpayers’ funds handed over to claimants. It lies in the sacralisation of a backward-looking culture of grievance. As Winston Peters, who opposed the initial legislation, warned years ago, such a system was a recipe not for progress but for creating “a bitter and divided nation with separate systems for Maori and non-Maori” – as it plainly has.

Yet despite that experience, the Albanese government, trapped in an idea-clot, remains committed to negotiating a treaty. That treaty, Megan Davis tells us, must be “about reparations for past injustices”. Should it come to pass, the real injustice will be to Australia’s future, which surely deserves better.

As New Zealand tears itself apart over the legacy of Waitangi, the fate of that treaty and of the American Indian treaties in North America contains many lessons for Australia.