I have written on numerous occasions that I despaired Pell’s trial would become a circus that overwhelmed everything around it and everything that had come before it.

And here we are.

The High Court found there existed “a significant possibility that an innocent person has been convicted because the evidence did not establish guilt to the requisite standard of proof.”

Justice has now been done. George Pell’s conviction has been quashed.

It is reasonable to conclude that the failed pursuit of one man has overshadowed the ugly history of clerical child sex offending. Meanwhile, the significant role of another institution in this litany of misery remains locked in darkness.

We need to understand our history and not accept a sanitised version of it. And there is no time better than now to examine the role of the Catholic Church and the Victoria Police Force who often worked hand in glove to bury their culpability in the most serious of crimes.

Clearly, one has been more successful with this act of deception than the other. And that needs to change.

I received a letter from the son of a police officer just last week. He told the story of his father, as a young uniformed police officer on foot patrol around the parliamentary grounds with another similarly youthful cop alongside him. They came across two men in a public toilet engaged in a lewd act. They detained and sought to charge the two men; one was a priest, the other a member of parliament.

The charges did not proceed, no action was taken but the two young coppers remained as loose ends – eyewitnesses to the sordid episode which by then had involved multiple senior police officers and the offenders in a conspiracy to pervert the course of justice.

The two young coppers were dragged into the Chief Commissioner’s office and given two options – leave the police force immediately or seek transfer as far away from Melbourne as possible. One chose Mildura, the other Hamilton in Victoria’s west where he stayed and rose to the rank of Inspector. That was 1946.

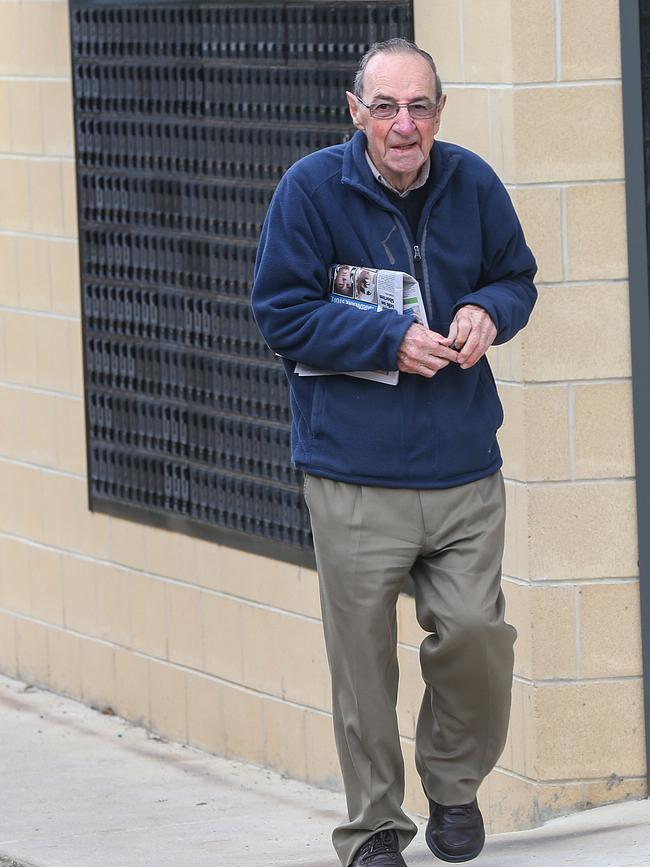

In 1956, a young police constable, Denis Ryan detained a priest, John Day after Day was found drunk, semi-naked and in the company of two prostitutes in St Kilda. Day was released without charge. Ryan asked a senior officer why the priest was not brought to account and was told, “short of murder, no priest would ever be charged in Victoria.” The senior officer explained that in the unlikely event a priest was charged, a group of police officers within the force would intervene and knock the charges over.

In Unholy Trinity, the book I wrote with Denis Ryan, we detailed a story where two detectives were in the process of charging a priest for child sex offences at Brunswick Police Station. It was alleged the priest had preyed upon boys at the nearby Don Bosco Youth Centre. The priest sat forlorn in the lock up. But not for long. A senior detective, Frank Rosengren burst into the interview room and demanded the two detectives drop the investigation immediately. The charges were dropped, the priest was released, and the two detectives were told to consider themselves lucky they still had jobs. That was 1960.

In 1962, Denis Ryan, a staunch Catholic and by then a detective constable was approached by a more senior officer, Fred Russell. Russell asked Ryan to join a group of police whose job he described as “ensuring priests did not come to grief in the courts.” Ryan declined the offer. Eight years later, Russell became the head of the Criminal Investigation Branch.

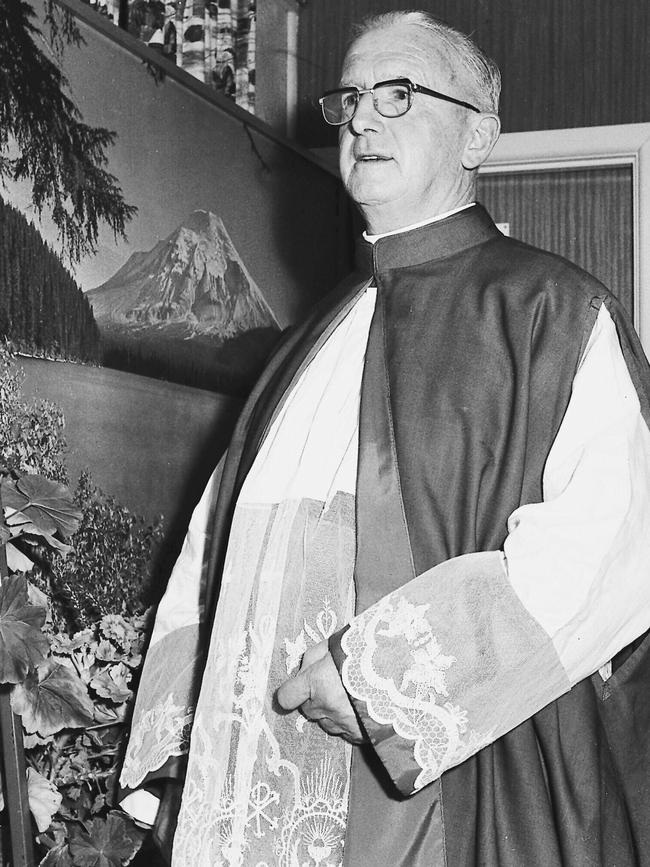

Denis Ryan attempted to prosecute an outrageous offender, Monsignor John Day in Mildura. Ryan lost his job. Senior police attended the diocesan office of the Bishop of Ballarat, Ronald Mulkearns and told him of Day’s offending. Day was not charged. Instead he was moved out of Mildura and placed in another parish, Timboon, near Warrnambool. That was 1972.

Three years later in the parish of Inglewood near Bendigo, police commenced an investigation into Gerald Ridsdale. Ridsdale had been a prolific offender since he was ordained a priest in 1961. He had been shanghaied around the Ballarat Diocese, from Ballarat to Apollo Bay, Mildura and Warrnambool but this was the first time we know of that he came under the scrutiny of police.

A Bendigo detective took one victim statement to Mulkearns in Ballarat in an effort to have Ridsdale transferred.

One resident of Ingelwood, an ex-cop himself, described the scene in his hometown. “All of a sudden, detectives came up from Bendigo. Then he (Ridsdale) was gone.”

Shortly afterwards, a detective travelled to Ballarat and met with Bishop Mulkearns to tell him Ridsdale would not be charged, but they thought he was guilty and should undergo therapy.

Just to be clear, Ridsdale was no low-level offender, “a fiddler” as victims often describe priests with wandering hands. One victim described Ridsdale “as the sort of man who would rape you and then threaten to kill you if you ever told a living soul about what had happened.”

Ridsdale who would later describe himself as “out of control” in Inglewood, would go on to offend at Edenhope, Bungaree and Mortlake, where he would be out of control again.

We might think these cosy, collusive arrangements between the Victoria Police Force and Church were driven by the pressures of sectarianism within the force, a force divided between Catholicism and freemasonry, where both protected their own. There is certainly some truth to that back then.

But by the mid-1980s those pressures had started to ease, driven largely by the decline of freemasonry.

Ridsdale was sent to Mortlake by Mulkearns in January 1981. The extent of his offending in that town of 1,000 people is difficult to conceive. It is said that almost every boy between the ages of 8 and 14 suffered some form of sexual abuse at the hands of Ridsdale.

He was shuffled out of Mortlake in 1984 by Mulkearns when the weight of his crimes became impossible to ignore. Mulkearns sent him to Sydney, where he offended again and again.

By this time, Victoria Police had taken an active interest in Ridsdale and this would lead to his first conviction in 1993 after he pleaded guilty to 30 counts of indecent assault against nine boys aged between 12 and 16 between 1974 and 1980.

But here again there is anecdotal evidence of certain police inveigling themselves on the outcome, tampering with evidence, victim statements disappearing. Ridsdale’s more serious crimes involving penetrative rape were not pursued at this time. He was sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment with a non-parole period of three months.

I know of one victim who had made a statement to VicPol detectives in 1985 alleging Ridsdale had raped him in 1983. The victim is now a police officer in another jurisdiction.

At the time of the offence, the victim’s father was ill in hospital suffering from cancer. It was thought he would not survive. Ridsdale raped the teen at the man’s home in Mortlake and then took the 40-minute drive to Warrnambool Base Hospital to administer the last rites.

The victim’s statement went missing and was never found. He contacted VicPol’s Sano Task Force several years ago but they had no knowledge of his allegations and inquiries confirmed the statement had vanished. That episode would form the basis of charges to which Ridsdale pleaded guilty almost a quarter of a century after his first conviction.

Recently, I became aware of three priests in Ballarat in the 1990s who had a number of things in common. They had all been expelled from seminaries for misconduct. All three were considered to be inappropriate persons to join the priesthood. But Bishop Mulkearns persisted and sponsored their training in other seminaries. They would all become child sex offenders.

With a light, however dim, now shining on the Ballarat Diocese, those three priests were considered potentially embarrassing and were asked to leave the priesthood. They did so. They weren’t laicised as far as I can tell. Their names feature in the annual Australian Catholic Directory; where they were ordained, what parishes they served. In the edition of the directory the following year, they were gone. Vanished. Like ghosts.

All three had been persuaded to leave the arms of the Church. They had come to the attention of police but were never charged nor subject to any police investigation. They were waved through and allowed to set themselves up as ordinary citizens in communities that could have no idea what threat they posed. That was 1995.

By this time, there were police engaged in the earnest investigation of offending priests and other clerics. They invariably describe their work at the time as largely unsupported by their senior colleagues. One detective who first brought the monstrous Christian Brother Ted Dowlan to justice wrote memos to senior police almost begging for the establishment of a task force. His requests were ignored.

Other detectives carried out their investigations largely in private, deeply suspicious of sharing information with colleagues in the fear that their investigations would be compromised.

That is the potted history. There’s more, of course. In Ballarat. In Melbourne and elsewhere in Victoria. It speaks of manifest failures, wilful ignorance and systemic corruption.

When we move to the present and VicPol’s Sano Task Force’s pursuit of George Pell ending in ignominy, the question must be asked, did Victoria Police seek to erase its dismal history by the failed pursuit of one man, a prince of the Church?

Consider an alternate reality where John Day had been charged and sentenced to a long term of imprisonment for his crimes against children in Mildura in 1972. Or if Ridsdale had been brought before the courts and prosecuted in Inglewood 1974. Hundreds of victims would have been spared the trauma of abuse. There is no other way of looking at it.

We understand the Catholic Church’s failings, the miserable felonious business of covering up and moving clerical paedophiles onto other parishes and new groups of unsuspecting victims. What is barely known is the role of the police in facilitating those crimes.

There’s no shortage of guilt. More than enough to go around.