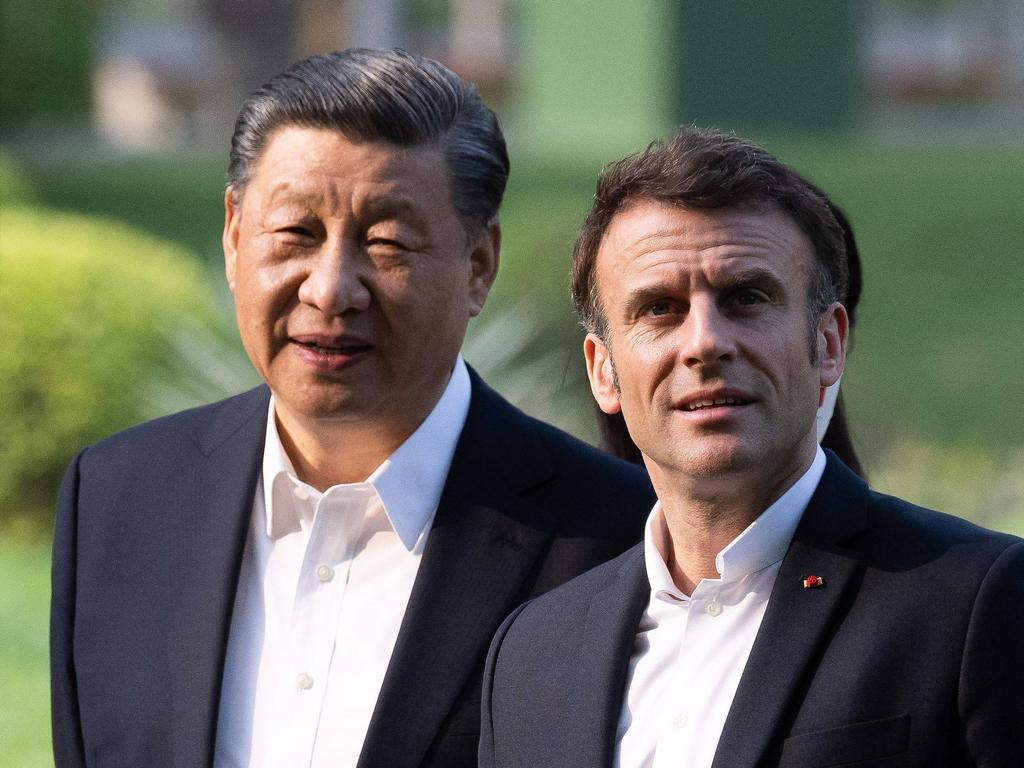

In those happier times Australia was signed up to buy French submarines, a topic high on the agenda as our PM flew to Paris as a guest on the President’s plane.

That night over a private dinner at the Elysee Palace with their wives, Lucy and Brigitte, Turnbull remarked that the newly elected leader was a living portrait of another great Frenchman.

“You look like a young Napoleon,” Turnbull said, whipping out his ever-present iPhone to show Macron images the 39-year-old President must have been deeply familiar with.

Macron scanned the likeness and said, impishly: “Don’t tell Angela (Merkel) or Theresa (May).”

It would surely not have escaped the attention of the German chancellor or British prime minister that their French counterpart had imperial ambitions.

In fact, Macron’s deepest desires went well beyond emulating a mere emperor. Early in his reign his aides planted the idea that the model they preferred for their President was “Jupiterian”; emulating the supreme god of Roman mythology.

Politico reported in June 2017 that “the French, aides explained, don’t want a buddy in the Elysee Palace. They want someone distant, and even mysterious”.

At this point, let’s pause and note that political staffers with overblown theories are just about the most dangerous people on Earth. Their first effect is pumping up the already overstuffed egos of their bosses. The second is that they conceive or encourage harebrained projects.

At the turn of the century a US presidential aide explained to me how the world’s sole superpower was going to deliver democracy to Iraq. It sounded like a stupid idea then and so it turned out to be. That war is the 21st century bookmark in the history of US moral, economic and military decline.

Anyway, if the French people ever desired to be ruled by a god, that feeling has clearly worn off. As I write from Prague, the eyes of Europe are on France, which is between its two rounds of legislative elections, following the shock dissolution by Macron of the National Assembly.

The reaction against the President has been fierce, with people pitching to the right and left in a revolt against his centrist party. The tactic of the centre and left in the second round is to withdraw third-placed candidates from run-off races to concentrate the vote against the party of Marine Le Pen and deny it an outright victory.

Whatever the final result, the message is clear: most are unhappy with the current settlement and want change.

People grow sick of godlike commandments that make their lives harder. The current French revolution is part of a significant grassroots revolt across Europe at the edicts of a distant, imperious technocracy. There is a range of grievances but a general disquiet at unchecked immigration and environmental rules that add to the cost of living.

And, whatever his faults, Macron understands some of the issues, if too late. He laid bare his fears – and his still imperial ambitions – in a speech at the Sorbonne university in April that was Castro-esque in length.

In it, Macron set the stakes dramatically high. “We must be clear on the fact that our Europe, today, is mortal. It can die,” the President said. “It can die, and that depends entirely on our choices. But these choices must be made now.”

That begins with Europe getting its house in order.

“Sovereignty cannot exist without a border,” he said.

That is something many of his people know innately but it is yet to penetrate the minds of too many on the left in Europe, the US and Australia. John Howard knew it two decades ago: lose control of the borders and you imperil national unity.

Travelling through Europe there is much to admire but one question nags: Why hasn’t it fulfilled its promise? In the 1990s some imagined that the 21st century could be European, as its grand union buried the wars of the past and unleashed the free movement of then 350 million people – as well as goods, services and money – across 12 states.

The EU now combines 27 states and boasts 447 million people but its share of the world economy has fallen from over 25 per cent to 17 per cent since 1993. Over the same time China has grown from 2 per cent of world GDP to over 19 per cent.

Macron believes Europe’s economic model “to have everything … doesn’t hold together”. That the world’s most generous social security system is a strength but it extracts an enormous amount of the wealth. That it abides by trade rules the US and China ignore. That the EU is bearing the cost of climate action but “others are not acting at the same pace”.

Here the President made a telling admission while arguing the European Central Bank should adopt growth and decarbonisation targets: “You cannot have a monetary policy whose sole objective is to address inflation, particularly in an economic environment where decarbonisation is a source for structural price increases.”

So, the cost of decarbonisation is permanently higher prices despite repeated pledges that it would drive energy costs down. Here Macron fails to make the obvious connection as to why voters might be angry.

He does, however, understand that Germany’s reliance on weather-dependent energy created a strategic risk because it didn’t work without Russian gas.

Macron laments Europe has “delegated everything that is strategic in our world: our energy to Russia, our security … to the United States and equally critical prospects to China. We need to take them back”.

Taking back control of energy means combining wind and solar with nuclear power. In defence, it means tooling up for a war fought without US support. If it is to compete economically it needs to invest trillions of euros in innovation.

The speech shows the President is good at articulating problems, and offers many solutions, but on one point his lack of self-awareness is Jupiterian: when he speaks of European humanism and its commitment to freedom. “It’s the choice not to delegate our lives to powers of state control, which have no respect for the freedom of rational individuals.”

Alas, the problem with the European Union’s governance is that it’s all about state control. It is the triumph of the bureaucracy, the rule of an elite technocracy. People don’t believe they have any real say over a state so remote from them it might as well be in Olympus.

Faced with this imperious regime, people abandon the project of the supra nation and retreat to their tribes. So the idea of Europe is good, the practice of democratic control over it is bad.

Every time there is a crisis in the EU the technocrats’ answer is “ever-greater union”. Maybe it should be “unity in diversity” and placing more trust in its people.

Malcolm Turnbull’s bromance with Emmanuel Macron began with their first meeting at the G20 summit in Hamburg in July 2017.