While some university chancellors, led by Jennifer Westacott, are honourably calling out anti-Semitism, vice-chancellors are frequently a far cry from the calibre that taxpayers and students deserve.

Once we understand the institutional failures in our legal system and our universities, it’s important to get the response right. We are in this mess because vice-chancellors, along with many others, have forgotten the important distinction between law and morality in a free and civilised society.

Vice-chancellors are meant to be well-educated folk. Universities are funded by taxpayers to be bastions of intellectual thought. This should mean university leaders, above others, are well-equipped and well-placed to explain the difference between law and morality.

Not everything that is illegal is immoral – a parking fine, for example. And, in a liberal democracy, not everything morally wrong should be prohibited by law. Much of what is called hate speech is a prime example.

University leaders should know better than most that the law – the most blunt of objects – is not always the right enforcer. Courts can credibly enforce only clear unambiguous laws. The problem with many laws on hate speech is they are subjective, unclear and essentially seek to enforce feelings, not facts. So it should come as no surprise that they are widely regarded as a dangerous joke dependent in large part on the whim of the presiding judge.

That said, university leaders should realise that limits on free speech are not solely, or even primarily, legal but moral.

Whether or not it is legal to call for “intifada” – a phrase that unequivocally threatens Jews – is not the point. It is immoral and it should therefore be condemned in the strongest terms.

The next, and separate, question is what consequences should flow from such behaviour. Universities frequently attach consequences to conduct that is legal but undesirable. Look at their fervour when policing what they deem disrespectful language. Mankind has been banned, to say nothing of pronoun crimes and misdemeanours. In other words, universities often sanction speech even when it’s not unlawful.

If universities find themselves between a rock and a hard place, it’s their own doing.

For many years their intellectual appetite has not stretched beyond low-hanging fruit. They have erected a superstructure dedicated to eliminating microaggressions in pursuit of what they dub their “equity, diversity and inclusion” project. Their websites are full of every conceivable, and inconceivable, codes of conduct governing behaviour on campus.

There are policies about gendered language, offering tips for students and staff to ensure they do not offend others by using the wrong pronouns. There are policies about “culturally inclusive calendars” too. And so on and so on and so on.

Monash University’s website boasts that its “Equity, Diversity and Anti-discrimination Policy suite strengthens the University’s commitment to providing an equitable and inclusive environment for students and staff.” Tell that to Jewish students on the receiving end of anti-Semitic bile at Monash last week.

The failure to act against anti-Semitism reveals that the EDI project is a crock.

A leader who understands the role of morality in a civilised society would understand that if you run a university, consequences should attach to anti-Semitism irrespective of its legality because it is immoral and because it threatens the safety of students and the proper, peaceful functioning of the university.

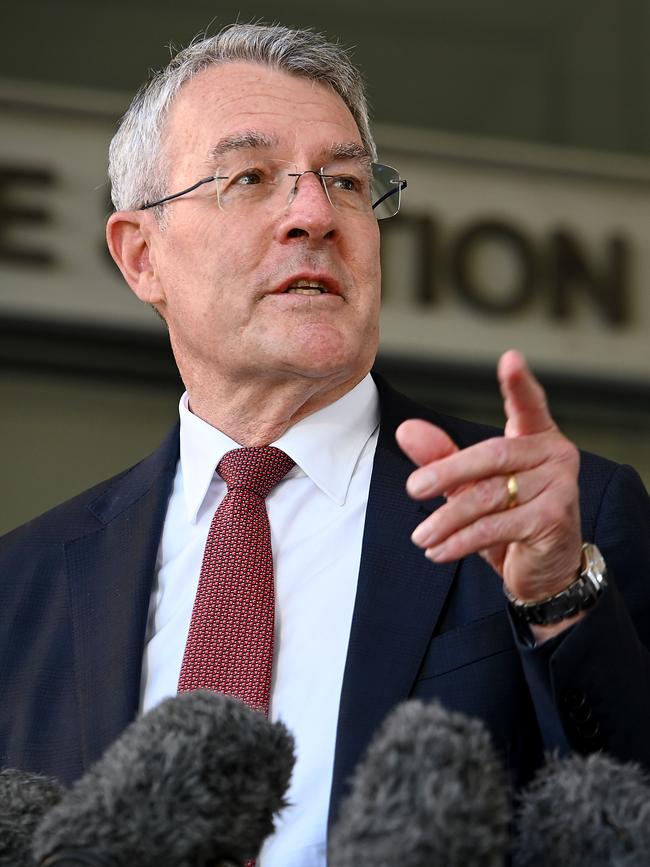

If university VCs keep mimicking low-level bureaucrats, hiding behind laws rather than showing moral leadership, their pay should reflect that. Last week, in a public show of cowardice, VCs from the nation’s grand old universities asked federal Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus for legal advice. They wanted to know whether protesters chanting “intifada” and “From the river to the sea, Palestine shall be free” breach our anti-discrimination laws.

The letter written by University of Sydney vice-chancellor Mark Scott and University of Adelaide vice-chancellor Peter Hoj on behalf of the Group of 8 universities says: “In possession of authoritative, definitive and enforceable advice, our universities would act immediately to prevent the use of these phrases on campus.”

Quite rightly, Dreyfus told them to get their own legal advice.

Before they shell out for that, VCs could exercise some inner moral judgment, gratis.

It pains me that universities where I studied – Adelaide and Sydney – where we have so many family ties, are now run by VCs who have made this about law when it is about moral fibre.

Students have been suspended in the past for far less than anti-Semitism. For example, Hoj was VC at University of Queensland when anti-communist activist Drew Pavlou was suspended for two years for breaching the university’s student integrity and misconduct policy. Pavlou had made public criticisms of UQ’s ties to Beijing.

The moral lapse by university leaders right now is even harder to bear given the legal mess. At one end of the spectrum, laws that attach legal consequences to hurt feelings have produced nothing good for the country. The application and shadow effect of section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act has turbocharged identity politics, victimhood and cancel culture. Witness the current litigation between Greens senator Mehreen Faruqi and One Nation senator Pauline Hanson.

At the other end of the legal spectrum are laws that prohibit incitement to violence. Incitement to violence is objective, identifiable and well understood. Such laws are necessary for public safety. Appropriately they are criminal in nature and attract severe penalties.

However, the current laws are woefully weak and subject to a “good faith” defence. This is madness. How can one ever incite violence “in good faith”?

Confusion about our laws does not get the vice-chancellors off the moral hook.

On the contrary, when laws are confusing, all the more reason for university leaders to use the power and force of moral condemnation to stop hate speech and anti-Semitism on their campuses.

The problem with VCs predates these student encampments. Once university leaders allowed academics to spout anti-Semitism in the lecture room, it would inevitably spread on to campus lawns. These same university leaders now stand before us helpless, hapless and pathetic.

At La Trobe University, provost Robert Pike told staff via an email last Wednesday that if protesters entered lecture rooms, “allow them to share the information they wish to”.

Pike said staff might wish to cancel the class and reschedule.

We should never forget that at a meeting of the nation’s university chancellors on May 2, this group of highly educated university leaders who routinely brag about their equity and inclusion policies couldn’t collectively agree to condemn anti-Semitic protests and further commit to suspending students for that misconduct.

Last weekend Westacott spoke out, followed by University of Western Australia chancellor Robert French and UQ chancellor Peter Varghese. But most chancellors – and vice-chancellors – remain hidden behind laws, muttering unconvincingly about free speech and uttering weasel words that all forms of racism are nasty. You don’t say.

Right now, the issue is anti-Semitism. Is that so hard to say that with meaning – and consequences? Some of these jokers don’t deserve top billing at a comedy club, let alone at a university.

The Gaza solidarity encampments at Australian universities reveal two things that may have slipped many people’s attention. First, free speech laws in this country are a bugger’s muddle. Second, too many vice-chancellors, paid more than $1m to lead our most esteemed universities, behave like low-level bureaucrats.