For once, elections are not about the economy

In every election in almost every country or jurisdiction, incumbents have triumphed, or hoped to, by offering stability, safety, competence and an explicit promise to keep their people united.

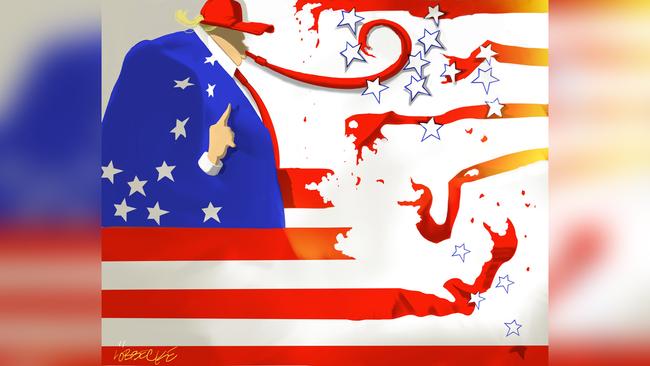

Donald Trump is the dishonourable exception. Trump has built his campaign around chaos, dysfunction and disunity. As someone who would vote for Joe Biden even if he were on a ventilator in an ICU, figuring that would be a far less dangerous option than a second Trump term, it is staggering that about 43 per cent of voters are still saying they will vote for Trump.

Despite his gross mishandling of the pandemic, his undermining or demonising of every American institution, including the presidency, his vicious abuse of every official sworn to serve him or every opponent critical of him, his incitement of racial and political violence and his encouragement of the malevolent QAnon, it remains a real possibility he could be re-elected.

Here at least, and across the ditch, even in these abnormal times, thankfully a few normal rules still apply. Leaders have resisted the temptation to sink as low as Trump. They might play rough, but they have not sought to profit by tearing their country apart or by turning one group of citizens against another.

In the ACT, few residents were surprised when Labor, in its 20th year of governing, was re-elected last weekend for another four years to govern in coalition with the Greens, while the Liberal vote went backwards. The surprise was that the Greens had done much better than expected, going from two seats to a certain five and possibly six.

Whether this was because of a post-black summer bushfire resurgence of climate change as an issue, or because voters wanted to give Labor a prod to smarten up without risking change to an untried alternative, is debatable.

Whatever, on top of the struggle by oppositions to get any traction these days, the Liberals had the wrong campaign for the wrong leader. Alistair Coe, 36 but who would still be asked for ID in a bar, looked like a boy on a man’s mission. Coe’s stunt-driven picfacs around cost of living, such as wearing boxing gloves or holding up a block of ice, only accentuated that. Any gravitas he might have had melted along with the ice he held up for the cameras as he pledged to freeze rates.

And as former leader Gary Humphries, the last Liberal chief minister, pointed out, the right-wing dominated ACT Liberal Party is completely out of synch with the bulk of its electorate. In the place that recorded the highest vote in Australia for a republic (68.27 per cent) and for same-sex marriage (74 per cent), the young Coe was against both, and then in May prematurely declared the COVID-19 pandemic was over.

At any other time, longevity might have worked against the ruling party. Not for Andrew Barr and Labor. It was a plus as they pointed out the inexperience of their opponents. In summer, Canberra was ringed by fires, yet this time they did not escape into populated areas. While the embers were still smouldering, COVID hit.

Despite nestling between NSW and Victoria, at the time of the election Canberra had been COVID-free for almost 100 days, longer than any other jurisdiction, thanks to an alert, compliant population, a public health system that worked and a government that took the threat seriously.

It is fair to say Canberra is almost completely unrepresentative of the rest of Australia, but the campaign lessons still apply Australia-wide. Barr, who acknowledges that at any other time the “it’s time” factor would have worked against him, says it came down to people trusting the government to manage the recovery as well as the crisis.

More emphatically, New Zealanders placed a high value on what Jacinda Ardern had offered, smashing the opposition Nationals led by Judith “the crusher” Collins who polled just 27 per cent. The vote showed New Zealanders’ priorities were safety and compassion first, economy second.

In Queensland, where the Prime Minister spent a week campaigning off the back of a well-received budget, Labor’s Annastacia Palaszczuk appears on the brink of victory. After looking like a dead duck at the beginning of the year, it is now possible Palaszczuk will either win outright or end up in minority government.

She is another politician who stands to be rescued by COVID-19 in a flight to safety by voters.

Taking up temporary residence in the Republic of Queensland will work well for Morrison at the next federal election, but the attempt to help LNP leader Deb Frecklington could rebound. Using one popular leader to prop up a less popular leader usually only succeeds in making the unpopular one look even weaker. If Frecklington falls far short, then it also leaves Morrison open to the charge — again — that his popularity doesn’t translate to votes.

Palaszczuk’s answer to questions about why Anthony Albanese wasn’t there trying to help her — because she didn’t need anybody holding her hand — was deadly. Almost as deadly as Morrison’s response to Labor’s unwise and untrue assertion that this was the Morrison recession. Playing to the government’s strength on economic management, Morrison charged that if you don’t know how you got into recession, you don’t know how to get out.

Labor’s attempt to hang the recession on Morrison was a blemish on what was an otherwise solid response by Albanese to the budget. His potentially deadly line, highlighting the absence of reform, was that the only legacy of the Morrison/Frydenberg budget was a trillion-dollar debt.

Both sides are rehearsing their themes for an election the Prime Minister suggests will be later rather than sooner by declaring himself a “full termer”. Essentially, Morrison will argue it’s time for stability, while Albanese will argue it’s time for change.

Morrison technically nominates the date. But in reality, like everything else, it will be dictated by COVID-19.

So far, incumbents here have benefited from their handling of the pandemic. No one can predict what the mood will be a year or 18 months from now. If there is an effective vaccine by mid-next year, maybe the government can afford to wait, allowing time for the economy to improve. Maybe that also allows time for people to forget about COVID-19 and turn their mind to other matters like dodgy land deals or sports rorts or other irritants now subsumed by the pandemic.

If there is no vaccine, voters could be fed up with it all, including politicians blaming COVID-19 for neglecting other things. They might grow impatient with the Prime Minister’s inability or unwillingness to influence the states and territories. Regardless of timing, they could even punish him for being in charge.