Closing the gillnet fishing industry was one of the things UNESCO insisted must happen to stop the Great Barrier Reef from joining the “in danger” list. The Prime Minister and his Environment Minister, Tanya Plibersek, have bent over backwards to comply. French newspaper Le Monde recently quoted sources close to UNESCO saying the difference between the new government’s attitude and the old one was “like night and day”.

Gillnet fishing for wild barramundi in north Queensland will end when the season closes on October 31 and will be illegal from the start of next year. It was banned at the insistence of a supranational organisation without any discussion in federal parliament or consultation with the industry. To describe it as undemocratic would be an understatement.

There is no credible scientific evidence showing how an annual catch of 200 tonnes of wild barramundi in onshore waters could damage the Reef. There have been no reports that stocks of wild barramundi are depleting. On the contrary, local fishermen say they have seldom been more abundant.

Yet from the end of next month the only place Australians will be able to buy Queensland wild barramundi will be on the black market. Gillnetting will continue in the NT and WA, but since two thirds of the national catch comes from Queensland, wild-caught barramundi will be priced out of reach for most consumers. Everything else will be farmed and much of it will be imported.

The sentence on gillnet fishing came out of the blue. Commercial fishers in Queensland reportedly found out less than an hour before a general announcement released by Plibersek and the Queensland government on June 5. The announcement was apparently timed to coincide with World Oceans Day, but no one had considered it worth warning the people whose livelihoods were about to be destroyed.

“It was just gut-wrenching to have that told to you in a press release,” gillnet operator Neil Green told me at the weekend. “No one in Queensland who managed the fishery was ready for this. Here we are three months down the track and we have no idea whether we’re going to get compensated, we’re going to be bought out or what the future is.”

Neither government had given much forethought to the impact on towns such as Ayr, where a thriving fishing industry operates around the mouth of the Burdekin River. The local ice producer is wondering if his business will survive. Business for the suppliers of marine services has tanked. Licence holders are stranded with expensive boats for which there is no longer a market.

It’s unclear whether Plibersek has visited the region, so far as anybody can tell. The decision and the announcement were made in the safe confines of Canberra, a city where the major industry is messing with other people’s lives.

“We know one of the most immediate threats to health of (the) Reef is unsustainable fishing practices,” read the June 5 press release in a section headed “Quotes attributable to the federal Minister for the Environment and Water”. She said dugongs, turtles and dolphins are caught in nets and drown.

If Plibersek could spare time to spend a morning with Green and his daughter, Sienna, working the creeks and mangrove swamps near the mouth of the Burdekin River, she would have learned the allegations in her press release were pure fiction.

She would have watched Green release his nets meticulously weighted at the bottom and with corks at the top, at locations and at a depth where almost half a century of experience has taught him he’ll catch barramundi and nothing else.

No licence holder looking for a return on their investment in their boat, equipment and red tape would contemplate not complying with the reporting regulations. Green has never had to report the catching of dugongs, turtles and dolphins, let alone their drowning, because he has never had the misfortune to catch one in 47 years of commercial fishing.

The Queensland government keeps a record of wildlife deaths for which humans are responsible. The total number of dugongs caught in nets since 2012 is six. The total of koalas killed on Queensland roads is more than 3000. Cars and trucks remain legal, at least for now.

Green has repeatedly asked for scientific evidence to support the minister’s claims. He said the best answer he’d been given was that fish absorb carbon dioxide and hold it in the ocean. “I’m happy to consider the science, but I’m not going to cop this rubbish,” Green told me.

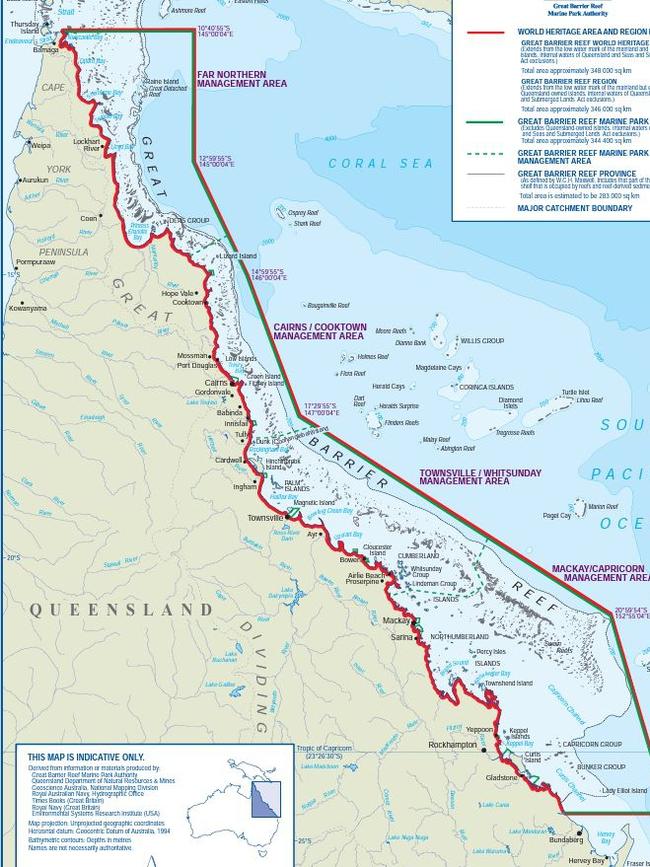

UNESCO’s jihad against gillnets began in April last year when a delegation of special investigators flew to Queensland to look for evidence of damage to the Barrier Reef. Like Hans Blix, the hapless former Swedish diplomat sent to Iraq to search for weapons of mass destruction, the delegation was hardly likely to return with a report declaring fears were misplaced.

The delegation spent 10 days in Queensland meeting more than 100 people, including politicians, bureaucrats, academics, representatives from tourism and the ever-expanding reef conservation industry. None of them worked in the kind of jobs where you get your hands dirty. They met representatives from the World Wildlife Fund, Queensland Conservation Council and the Australian Marine Conservation Society, whose organisations had joined the confected campaign against gillnets.

They apparently met nobody from the commercial fishing industry, let alone the licence owners whose worlds they were about to destroy.

When the Hawke Labor government banned logging on the Atherton Tablelands in 1987, then environment minister Graham Richardson had the decency to show up at Ravenshoe and look squarely at the faces of the workers who were about to lose their jobs. That is not the Albanese government’s style. It rubberstamps decisions made in Paris with little consideration for the dignity of working Australians, incomes, communities or fairness.

It is the same approach it has taken to develop the industrial-scale wind and solar plants blighting scores of regional communities from Tasmania to far north Queensland.

The pattern is clear. Albanese is dancing to the tune of the inner-city elites who call for greater action on climate change, knowing they’re exempt from paying the cost. His government is making costly decisions in energy and environmental policy without bothering to ask if they are needed or will be effective.

It is perfectly understandable. When the Prime Minister and his Environment Minister represent adjoining inner-city seats that are both under sustained attack from the Greens, the dignity of working people in regional communities is probably the last thing on their minds.

Nick Cater is senior fellow of the Menzies Research Centre.

If Anthony Albanese planned to price wild-caught barramundi off the menu before last year’s election, he forgot to mention it to the electorate. However, it probably had yet to enter his mind before he flew to Paris to talk to UNESCO in July 2022.