Exit of a Labor warrior should ring alarm bells for Albanese

And it leaves a gaping hole in not only the talent pool of Anthony Albanese’s cabinet but the modern Labor Party more broadly.

“He hates them” says a close friend of the cabal that has taken over factional control of the party.

“And you can hardly blame him.”

Shorten’s enmity toward Albanese, which is returned, is legendary and unsurprising.

But that has subsided for Shorten. A reconciliation with his own demons, if not his enemies, has supplanted bitterness.

His equally measurable venom for his own Victorian colleagues – those coalesced around deputy Labor leader Richard Marles, and who systematically set out to destroy Shorten after the 2019 election loss – has also been shelved.

They never got him. He leaves on his own terms, his integrity intact and his legacy now inscribed in the annals of the labour movement.

And for a future with arguably more prestige, better pay and a grander house.

Hence the decision to depart became all the less difficult for Shorten.

But this has taken a sea-change in belief for a deeply tribal Labor warrior, a tempering of ambition and a reconciliation with the past.

Shorten has been a member of parliament for 17 years. And he was a figure starting to loom large over the broader Labour movement long before that. He has lived and breathed politics since his teenage years.

After his university days, as a young unionist, he and another school mate from Xavier College, Luke Donnellan, made it their mission to challenge the Victorian division dominated by the left.

They railed against the sight of left-wingers driving around in BMWs. It was a pursuit of the pure. Right-wing Labor warriors on a mission of social justice guided by commonsense Jesuit values.

The Beaconsfield mine disaster elevated Shorten, by then the head of the Australian Workers Union, to the national stage.

His trajectory was beginning to mirror that of a young Bob Hawke, catapulted into the parliamentary leadership as a firebrand union leader carried on the shoulders of his own charisma.

Shorten’s destiny almost seemed assured.

The boy from Maribyrnong was on a path to the Lodge.

Hubris, and an uncharacteristic accommodation of the left to maintain power as opposition leader, got the better of him in the end.

A fridge magnet in Shorten’s suburban Melbourne home, that he had bought from the Churchill War rooms, suggested otherwise.

And that of his pets, two British bulldogs Walter and Tilly.

“Never give up,” the magnet reads.

Friends who would come to visit took that as a sign that his political enemies would have to take him out in a body bag.

His enemies have been denied that occasion.

While Shorten was accused of taking the party to the left under his leadership, with a monumentally flawed, class-war-inspired anti-wealth and anti-business agenda, his legacy now remains closer to his roots as the ballast of commonsense in a cabinet and caucus that has veered so radically to the left.

Shorten is now often regarded as a lone voice of sensible, traditional right-wing ideological reason, with the NSW Right having long since vacated the field.

This is ironic. But not unsurprising. Shorten’s charm and belief in the art of the deal endeared him to many. It also created enemies.

But he also reinvented himself as one of the government’s best communicators, with a common person’s touch that has become a redundant feature in the new Labor government.

Shorten has been mulling the idea of his departure for months.

The role of vice-chancellor at the University of Canberra had been dangled before him months ago.

But he hadn’t seriously considered it until recently. He made a formal application on August 21.

Colleagues and friends had noticed a sense of serenity about Shorten long before that. He had finally made his peace with his political demise.

Until then, he had held on to the ambition that he may one day return to the leadership, in the belief that the Albanese experiment would ultimately fail.

“He has been talking about leaving for a long time but I thought he was just de-stressing,” says a close friend.

“I knew the university gig was there, but I think he only came to the decision recently.”

Shorten’s departure before the next election says more about what he thinks of Labor’s prospects at the next election than perhaps it does about his own ambition.

Those close to him say he was coming to the belief that the government was on a path to potential defeat at the next election.

It sends a sobering message to what the most savvy person in the party thinks about its future, says another colleague.

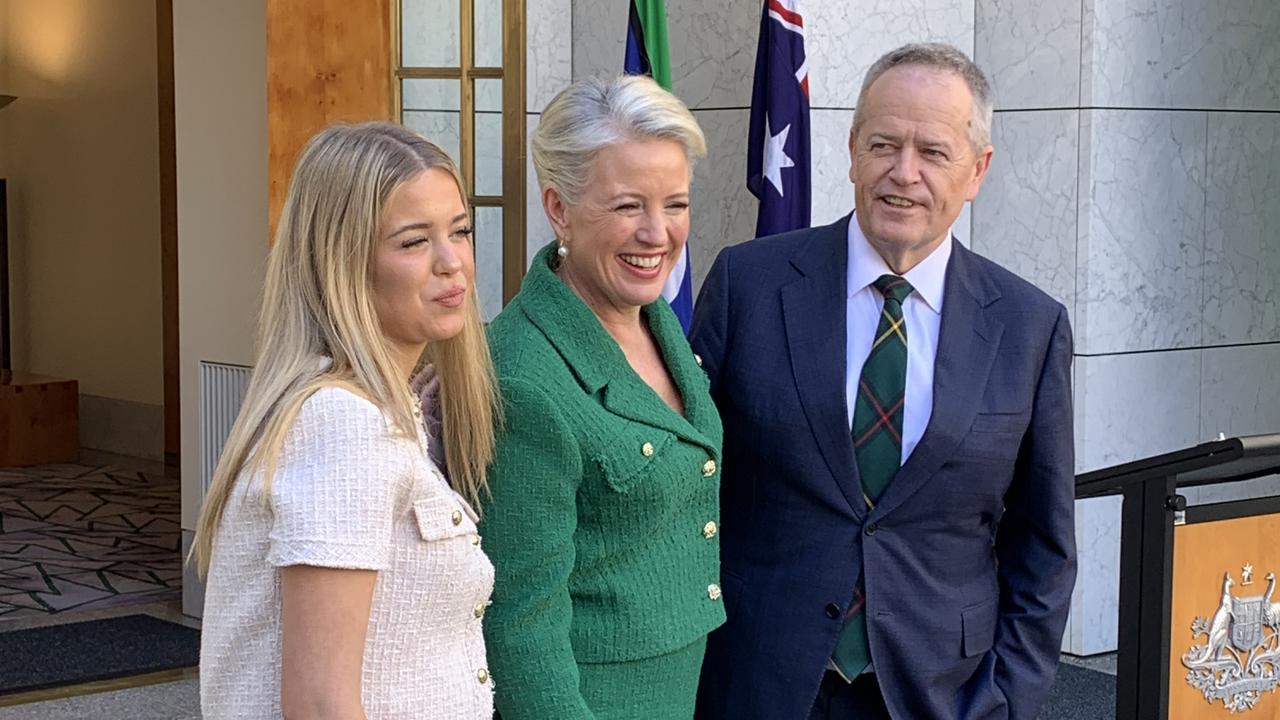

Shorten and Albanese both said what they needed to in the Prime Minister’s courtyard on Thursday when Shorten announced his retirement.

And there would have been some sincerity in their words toward each other.

But what can’t be dismissed is the reality that Shorten’s loyalists believe that he is now the ship leaving the sinking rats.

Bill Shorten’s decision to quit politics after almost two decades may come as a shock to many but no surprise to the few close to him.