ASIO was set up at the beginning of the Cold War because there had been Soviet agents inside both External Affairs and the office of the minister for external affairs (HV Evatt). Yet ASIO itself was then penetrated by Soviet moles. This was suspected in the 1970s, by the Hope royal commission; investigated in vain in the 1980s (Operation Jabaroo), and confirmed in the 1990s.

Between 1985 and 1994, three Soviet defectors, Vitaly Yurchenko, Oleg Gordievsky and Vasilii Mitrokhin, and former head of KGB foreign intelligence Oleg Kalugin, testified to ASIO being penetrated. The CIA had long suspected a leak in Canberra and the discovery of Aldrich Ames within the CIA in 1994 was a reminder of how much damage even a single mole could do.

A fresh investigation into ASIO, when Paul Keating was prime minister, concluded there had actually been multiple moles – five or more. This is astonishing on the face of it. In Washington and London, at the height of the Stalin era, no single organisation had this many Soviet moles. MI6 had two (Kim Philby and George Blake), as did MI5 (Anthony Blunt and a still unidentified GRU (Soviet military intelligence) mole (codenamed ELLI). Many others were liberally spread across British institutions.

In Washington, there were multiple Soviet moles inside the State, Treasury and Justice departments, but those agencies were much larger than ASIO. It was eventually learned there had been several hundred Soviet moles throughout the American government, key industries, academia and the press in the 1930s and ’40s.

The reckless accusations against innocent people made by senator Joseph McCarthy in the early Cold War years gave mole-hunting a bad name. For decades, men such as Alger Hiss, Laurence Duggan and Harry Dexter White were vehemently defended against accusations of spying. But the evidence is now unimpeachable that those three and many others were Soviet moles.

In Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America, John Earl Haynes, Harvey Klehr and Alexander Vassiliev provided chapter and verse. Their most crucial observation was that while McCarthy made wild and irresponsible accusations, the revelations by repentant Soviet spies Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers that there were dozens of moles in Washington were accurate; and that, in fact, they “only knew the half of it”.

That is the Cold War context for understanding the penetration of ASIO. The defectors testified that the yield from these moles, in terms of Five Eyes intelligence, was invaluable. Yet the story has been kept under wraps by both sides of politics. It’s time it was brought out into the open.

When the official history of ASIO was published a few years ago, the authors skirted around the issue. They knew the truth, but had been forbidden, contractually, from publishing the facts of the case or any names. Instead, they quoted me on the subject and tacitly admitted I was correct. But I had no names and no hard evidence.

Nigel West, a highly respected historian of Cold War intelligence, names five ASIO officers, including a husband-and-wife team, as having been identified as the moles. Under the ASIO Act (1979) an Australian citizen is forbidden to disclose such names. But West’s evidence is convincing, especially as regards the identity of the key mole to whom the defectors were referring many years ago. That individual was confronted by ASIO after his retirement, but refused to cooperate. He has since died.

We are therefore left in the strange position of being able to read West’s book, but not quote the names of the moles in the press. This situation allows the likes of Victoria University’s Phillip Deery, in Spies and Sparrows: ASIO and the Cold War, released recently by Melbourne University Publishing, contriving to dismiss the very idea there was any serious Soviet espionage in this country during the Cold War. He clearly missed the main game. And it’s important we don’t miss it right now, with pro-Putin or pro-Beijing apologists playing down or dismissing concerns about espionage and influence operations.

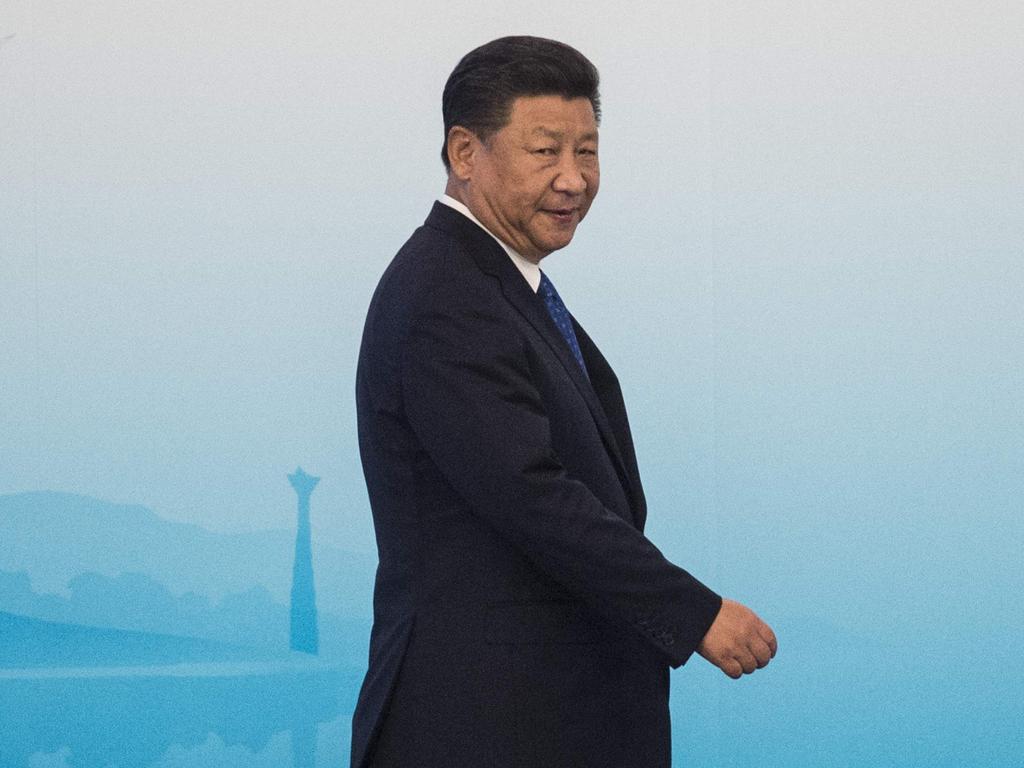

Right now, as Alex Joske has just shown in his fine new book, Spies and Lies: How China’s Covert Operations Fooled the World, we face a situation strictly comparable to that of the early 1940s across the West, when Stalin had agents all over the place. The agents, as of old, work for Russia and China. Xi’s and Putin’s spies and enforcers, agents of influence and fellow travellers are numerous and our security intelligence capacities are stretched to the limit.

Putin has discredited himself and Xi’s wolf warriors have failed. But the arm wrestle with both – and their spies, moles and agents of influence – is far from over. Acquaint yourself with the history. What’s going on now rhymes with it.

Paul Monk is a Fellow of the Institute for Law and Strategy (London and New York). He is the author of Thunder from the Silent Zone: Rethinking China (2005) and Dictators and Dangerous Ideas (2018), among other books.

With Vladimir Putin’s destructive war against Ukraine, and the ambitions of Xi Jinping causing growing geopolitical tensions, we must confront the reality of Russian and Chinese espionage and influence operations. Yet we in Australia still haven’t come to terms with our counterespionage failures in the Cold War. Clearing up that history would help us get our challenges in clearer perspective.