Diary of a Melburnian in our second winter of discontent

Wednesday, it was tentacles of panic shooting through the suburbs. People were flocking to get tested, with three- to four-hour waits in car queues, and thousands turned away. People spooked about AstraZeneca blood clots were now rushing to get vaccinated, fresh fear cancelling out hesitancy, with the numbers jabbed doubling in one day. Morning traffic had shrunk; pedestrians had abandoned the CBD — caution born of painful past experience was quick off the mark. Even panic buying in the supermarkets was back, with toilet-roll shelves emptied — first indicator of the adrenaline spurt of manic communal anxiety. Oh no, could it already have come to this?

Thursday, the infected numbers were rising sharply, with 11 new cases. The venues deemed potential sites of contamination were multiplying by the dozen, every hour, approaching 200 in all by mid-morning. That level of risk meant the silent virus monster was out of control. Of the two opinion-leading morning radio presenters, Virginia Trioli on ABC 774 was mouthing the word glum, while Neil Mitchell on 3AW was in a very sober mood.

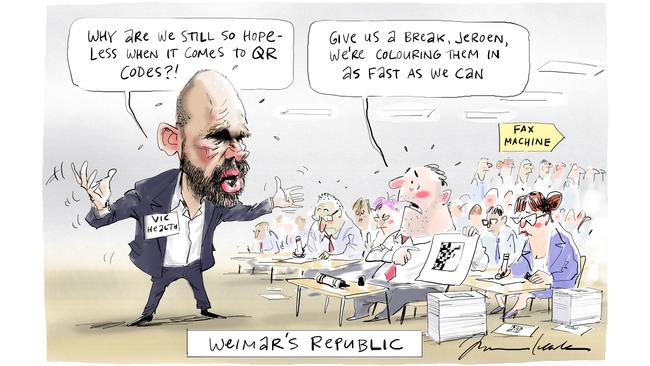

As the media temperature rose, reports multiplied of state tracing and contact at breaking point. The Victorian government has repeatedly bragged about its system as gold standard, world’s best practice — it was being shown up yet again to be incoherent. In the first alert, of an infected man from Adelaide, the wrong supermarket was listed as a site he visited, a mistake not rectified for around two weeks; venues listed to be closed weren’t contacted; people told to isolate for attending an event they had never heard of; others given an instruction one minute, a different one by someone else an hour later; advertised hotlines understaffed and never answering calls. And so on. This sentiment is resurfacing, a quite uncharacteristically contrite one for Melbourne, re Sydney: why can’t we have Gladys for premier?

Yet this time, the mood seems different. A torpor is in the air. Too weary to complain. Too tired. Resignation rather than outrage. “Oh well, you can’t expect too much from governments.” And this is hard to deal with, the speed with which Covid erupts, the ease with which it spreads. Maybe we’ve just had bad luck. Decisions are difficult, like when to open borders. A whole city has been shut down by a single Australian who reportedly returned from India after attending a wedding. That at least means, for the moment, however harsh, Australia has to shut down its repatriation flights.

The Chief Medical Officer noted more than 10,000 primary- and secondary-contact individuals needed to be found and tested — an impossible task even for an efficient health bureaucracy.

There were plenty of objective grounds for complaint. The Victorian Health Department had failed again. The federal government’s haphazard administration of vaccine distribution and delivery was exposed, with its misjudged casual attitude, proclaiming this “is not a race”. The recent Taiwan example, of a country that had dealt extremely effectively with pandemic prevention for more than a year, yet had suddenly been overwhelmed by a surge of infections, was just one indicator of the virulent threat ever near at hand. Some epidemiologists had been warning that an outbreak like this was inevitable. Parts of the media had been irresponsible, highlighting isolated cases of the very few serious reactions to the AZ vaccine, fuelling community fear. And the people themselves have been partly to blame, in their complacency, as reflected in vaccination hesitancy.

Resilience was top of the concern list this time, as Lockdown 4.0 entered its first days. The CBD has had a very slow, limping, and partial recovery from the ghost town it stagnated into in 2020. The one major lasting victim of Daniel Andrews’ long lockdowns was the now feeble heart of the world’s regularly acclaimed most liveable city. The streets had been struggling back to pre-pandemic densities; the cafes and restaurants that had survived three lockdowns were filling. Public servants, while resisting full-time return to office work, were drifting back. The County Court was about to restart normal jury trials.

But office vacancy remained at about 50 per cent; and swathes of apartments were still empty, with sale prices dropping by 30 per cent, and more. Students had not come back; exclusive designer shops in Collins Street open but vacant. Small, struggling service businesses may now give up. The Melbourne CBD is like a person laid low for a year by debilitating pneumonia, struggling back hesitantly to his feet, limping out the front door, only to be struck by an icy blast of reality, and relapsing.

This world pandemic has been accompanied from the outset by ruthless uncertainty — arguably its defining characteristic. Its path seems to defy prediction at every turn. In Melbourne there was new symbolism. The home sites for the greatest local boost to communal morale, the two football stadiums, are both deemed contaminated, although permitted to function with empty stands. The Premier remains absent from work after months with a serious back injury. The head of contact tracing has himself been on sick leave.

The mood changes from day to day, as is only human. On the one hand, there are restaurant proprietors and gym owners livid with rage. On the other, this is a stoical, law-abiding and socially respectful society, with initial resignation giving way to a shrug of the shoulders and a more spirited, if subdued, let’s get on with doing what we have to do. We have experience of this. Plan for next week; but brace for worse, given the lingering fear the lockdown is going to last longer than seven days. On Friday, an impressive 57,000 people went for virus testing, driven by anxiety, but also a sense of social responsibility.

Surgeons reschedule. Cafes return to takeaway only. Parents gear up for home schooling. The AFL adapts. Radio presenters rise as an important voice of the community, quickening the pulse of public conversation, urging listeners to get vaccinated, as they dispel paranoid fears.

Infection numbers held steady on the weekend; testing was high, but there remained a frightening number of contamination sites. The vaccination program was hopelessly clogged with attempted mass bookings. On Sunday, an aged-care health worker tested positive, ominous given the failure to comprehensively vaccinate homes for the elderly.

The empty streets are dank and ghostly; the moment is gloomy, the future once again uncertain.

John Carroll is Professor Emeritus of Sociology at La Trobe University.

You could hear the mass collective groan echoing across Melbourne last Tuesday. The truth was slowly dawning, like a choking dank fog creeping in from across Port Phillip Bay to clog the lungs of the city. As winter approaches, here we go again. And we’d just started to enjoy normal life. Victoria seems to have the Australian monopoly on Covid bungling. Victorians have a near monopoly on Covid suffering.