While most of us were having a break and munching away on hot cross buns and Easter eggs, spare a thought for the Treasury officials (and indeed the Treasurer himself) who doubtless spent part of the break preparing for the budget. It’s only four weeks away.

These days, budgets are as much marketing exercises for the government of the day as they are statements of fiscal policy and spending and revenue plans. Technically speaking, it’s not really necessary to have a budget – not all countries have them. What is required is the passing of the appropriations bills so the government can continue to function and bills to change tax laws if necessary.

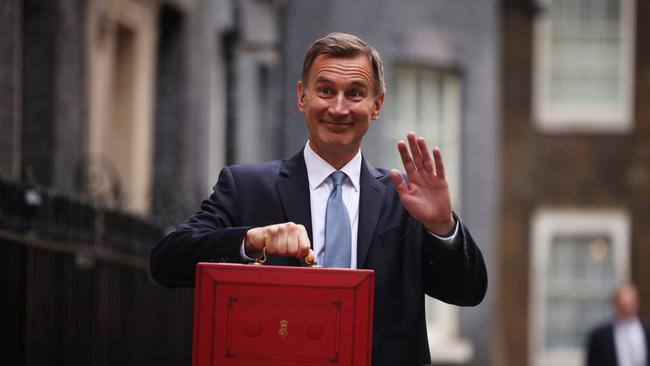

Our lockup arrangements, whereby journalists and other interested parties are given confidential, prior access to the budget documents for several hours before the Treasurer’s speech, are also unusual. In the UK, the Chancellor simply stands up in the House of Common and delivers that country’s budget.

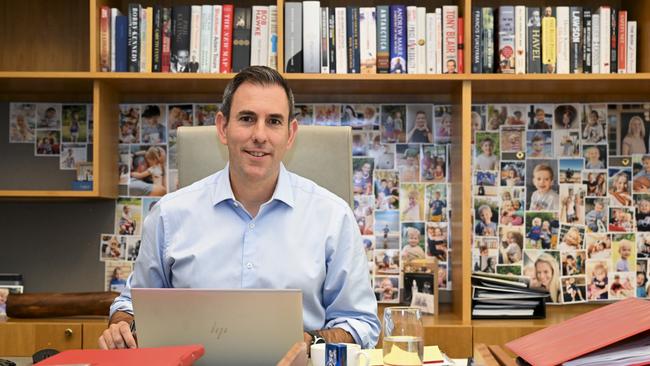

So what does this year’s budget hold and what are the challenges facing Treasurer Jim Chalmers? It’s worth getting several things straight at the beginning. When Chalmers delivered his first budget last year, he predicted that the budget deficit for this financial year would come in at $37bn. It will be much lower than that.

The main reason is that the hopelessly inaccurate assumptions of Treasury about commodity prices – they were expected to have tanked by now – haven’t come to pass, leading to much higher company tax revenue. Close to full employment has also meant fewer people on welfare. Throw in a dollop of bracket creep and the budget position will be significantly better.

Chalmers’ line about the trillion dollars of government debt Labor inherited is also looking particularly ropy. It’s actually a tad over half a trillion dollars, which doesn’t have the same ring to it. This the result of the combination of the improved budget bottom line and rising interest rates leading to a fall in the face value of government debt. (Hats off to the Australian Office of Financial Management which managed to lock in a fair chunk of government debt at very low interest rates.)

This said, one of the fastest-growing line items in the budget will inevitably be net interest payments, particularly from 2025-26 when some of the low-interest debt will need to be rolled over. In the October budget, net interest payments were projected to be over $26bn in 2025-26 compared with under $14bn this financial year.

The central challenges for Chalmers are three-fold. First, the demands of the spending ministers will need to be met with a degree of resistance. Secondly, any cost-of-living relief measures need to be achieved within a tight fiscal framework. Finally, the less fiscal policy achieves the higher interest rates will be. This means ensuring any ongoing revenue gains associated with high commodity prices are banked rather than spent. Phil Lowe, governor of the Reserve Bank, has said as much.

This brings me to the point about the cack-handed way in which Treasury has dealt with commodity price forecasts and the anticipated change to the methodology. For example, Treasury in October claimed that by the end of this March quarter, the iron ore price would have declined from $US91 per tonne to $US55 per tonne. The actual figure was over $US120 per tonne. There was no other supporting evidence why commodity prices were expected to collapse in such a short period of time – it was just an assumption, a convention.

Treasury secretaries have stubbornly defended this ridiculous practice of bunging in long-term commodity price averages within the budget year. Rather than being found to err on its main budget forecasts, blame could always indirectly be laid at the (stupid) commodity price assumptions. In reality, there were always alternative methodologies and it may be that this year’s budget lays them out. They include using the forward price curves for the key commodities or consensus price forecasts of the key market participants.

An even more cynical interpretation of Treasury’s approach to commodity prices relates to the potential brake it creates to frustrate the government’s spending ambitions. At the end of the day, however, it is not up to the bureaucracy to hoodwink the Treasurer; rather it’s the bureaucracy’s role to provide frank, fearless, honest advice.

Recall here that Treasury has been happy to change its assumptions about productivity growth – it is no longer 1.5 per cent per year but 1.2 per cent. The perplexing insertion of long-term key economic parameters in years three and four of the forward estimates was also ditched.

Budget rules have played an important role in guiding the actions of the Treasurer as well as helping spending ministers in their decision-making. For reasons that are not completely clear, there were no specific, numerical budget rules laid out in last year’s October budget.

To be sure, there were good parenthood statements such as “improving the efficiency, quality and sustainability of spending” and “focusing new spending on investment and reform that build the capability of our people, expand the productive capacity of our economy, and support action on climate change”. All very uplifting, but just not helpful for the conduct of fiscal policy.

The closest Chalmers came to setting down any actual budget rules was the following: “Directing the majority of improvements in tax receipts to budget repair” and “limiting growth in spending until gross debt as a share of GDP is on a downwards trajectory, while growth prospects are sound and unemployment is low”. On this last directive, it should be borne in mind that government spending is still proportionately well above pre-pandemic levels and that the last phrase is a significant qualifier.

What we really need are budget rules that contain objectives and specific targets: running a balanced budget over the cycle; constraining real spending growth to 2 per cent per year; limiting government spending to 25 per cent of GDP, and; limiting government debt to a certain percentage of GDP, are all examples. Not only do rules steer the Treasurer in the right direction, they also provide strict fiscal accountability. Without these rules, the fight against inflation may be longer and more damaging than need be.

According to a number of important US economists, including professors John Cochrane, Eric Leeper and John Barro, it is plausible to think the recent inflation has been principally driven by government spending (which is accommodated by permissive monetary policy). In the context of framing this forthcoming budget, Chalmers might care to spend some time reading up on this.