Dark hour when we leave allies to their fate

What is often overlooked is that about 110,000 of those evacuated were not British but French. Churchill fully appreciated that Britain’s honour was at stake and that to abandon its partners to their fate would be a shame beyond measure.

Fortunately, there were no immigration officials stationed on the beaches to make sure the French soldiers met “rigorous health, character and national security requirements” before they were eligible for rescue. But that is exactly the approach the Australian government is taking towards Afghans who supplied critical support to Australians who served in Afghanistan with the Australian Defence Force or worked in the delivery of Australia’s “whole of government” aid program.

With Afghanistan teetering on the brink of disaster thanks to Washington’s decision to cut and run, these desperate Afghans are in appalling danger as a result of their associations with Australia. The Taliban, tearing through diverse parts of the country, has a murderous record: in August 1998 it killed 2000 people in just three days, in a massacre one writer called “genocidal in its ferocity”.

Yet despite widespread calls for a special rescue operation, the government has become bogged down in red tape. The notion that Afghans who have worked loyally for Australians on the ground need to be vetted for good character or “national security” by clerks in Canberra is ludicrous.

And the notion that they could be left to their fate because of poor health or disability is downright sickening.

Moreover, the government has been relying on a resettlement framework established by a 2012 legislative instrument promulgated in entirely different times by the Gillard government.

If the situation in Afghanistan had become so dire that it was necessary to shut down the Australian embassy in Kabul with only three days’ notice in late May, it should be obvious that a legal framework of such antiquity was likely to be badly out of date.

This particular instrument limited access to special visas for vulnerable Afghans to “non-citizens employed with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Australian Defence Force, the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) or the Australian Federal Police”.

The killer term here is employed. Large numbers of Afghans who are in acute danger worked for subcontractors of the kind that routinely implement major components of Australia’s aid program.

DFAT has been responding to pleas for help with a chilling form letter that states: “The Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs and Trade has considered your application. Unfortunately, you are not eligible for certification under this visa policy as you were not considered an employee of one of the Australian government agencies identified in the legislative instrument.”

The Taliban, of course, does not distinguish between employees and contractors when choosing whom to kill. This is no doubt why former prime minister John Howard recently stated, “I don’t think it’s something that should turn on some narrow legalism.” Such lethal legalism can be overcome with the stroke of a pen.

And if this legalism were not sufficiently surreal, on June 3 an official testified to a Senate committee that once visas had been granted to applicants who had overcome all the earlier obstacles, “they will take commercial options to travel to Australia”.

One wonders whether those who are implementing the scheme have ever been anywhere near a war zone: when shells start to land at airports, “commercial options” are usually among the earliest casualties.

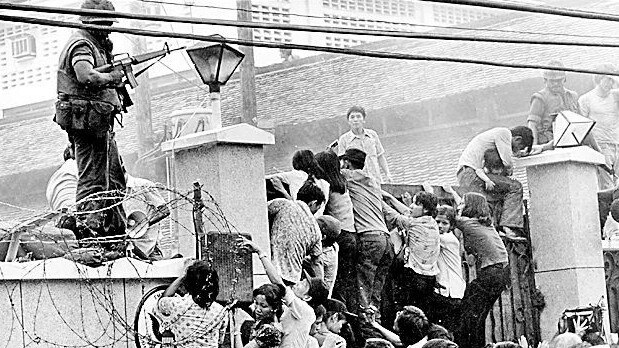

Unfortunately, this kind of shabby abandonment by politicians has a long history in Australia. In 1975, as the South Vietnamese stronghold of Saigon fell to the communist North Vietnamese, the Australian government, in a cable recently unearthed by journalist Karen Middleton, ordered: “Locally engaged embassy staff are not to be regarded as endangered by their Australian embassy associations and therefore should not, repeat not, be granted entry to Australia.”

And in 1999, as Jakarta-backed militias rampaged in East Timor after the declaration of the results of the popular consultation on the territory’s future, an MP approached the government with a proposal to establish a safe haven near Darwin for East Timorese refugees. The response he received was that “if they wanted short-term visas, they’d have to make applications through Jakarta”.

This stands in stark contrast to how ordinary Australians respond to mates in need. In 1999 during the siege of the UN compound in Dili, more than 2000 Timorese sought shelter with the UN in the compound. Timorese locally engaged staff already had been targeted and murdered by the militias. Even in that dire situation, bureaucrats tried to prevent the evacuation of the Timorese. AFP and UN staff in the compound refused to leave unless the Timorese were brought out with them. Australians demonstrated in the streets to save these people and an embarrassing stalemate was prevented when sanity prevailed and everyone was evacuated by Defence-assisted flights.

This demonstrates that when Australia wants to act, it can, and does it well. The situation in Afghanistan is just as dire. What is urgently needed, and what decent Australians plainly want, is for the government to find solutions to evacuate these at-risk Afghans regardless of legalistic trickery.

The combination of amoral leaders and unimaginative officials is the worst possible mix when decisive action needs to be taken, and fast, to save lives. Britain was fortunate to have a Churchill and a Ramsay in charge at the time of Dunkirk. Had those responsible for Australia’s current approach to vulnerable Afghans been in charge, we might all be speaking German now.

David Savage is a former officer of the Australian Federal Police. He served in East Timor, Mozambique and Bougainville, and has worked on war crimes issues for the UN and the International Crisis Group. He was attacked in Afghanistan in 2012 by a Taliban suicide bomber while overseeing aid projects in Oruzgan. He is author of Dancing with the Devil (2002). William Maley is emeritus professor at the Australian National University and author of The Afghanistan Wars (2021).

One of the most dramatic events of World War II was the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from the beaches of Dunkirk from May 27 to June 4, 1940. Operation Dynamo, ordered by prime minister Winston Churchill, commanded by vice-admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay and executed by the Royal Navy and a flotilla of fishing trawlers, pleasure craft and other small boats summoned to action because of the desperate situation, successfully collected 338,226 soldiers and transported them to England.