Damaging Covid rule demands more than token inquiry

Far more people were negatively impacted by the rules to deal with Covid than by the disease itself. Travel was drastically curtailed, lives put on hold, public events disrupted, and schools and businesses intermittently closed.

For Melburnians it was even worse, with most people locked in their homes for 23 hours a day, social contact virtually banned, curfews in place and freedom protests brutally dispersed with tear gas and rubber bullets – even though 99.9 per cent of us survived the disease.

Yet not only do we have an official inquiry that looks designed to rubberstamp the governmental over-reaction to a relatively mild illness but there’s also now a serious risk that the world will sign up to new rules designed to perpetuate totalitarian responses to so-called health emergencies.

The three-member panel the Albanese government has appointed to weigh the lessons of the pandemic is nowhere near the royal commission we should have. It’s headed by a long-time health bureaucrat who is assisted by two lockdown-supporting experts, one of whom – at least on her social media posts – often thought that harsh measures didn’t go far enough.

Critically, the inquiry specifically excludes the conduct of the states that were responsible for much of the overkill on lockdowns and vaccine mandates.

Almost inevitably, the inquiry will end up broadly endorsing governmental actions, even though these followed the “Wuhan plan” rather than the actual pandemic plans of management that Australia had carefully prepared and refined over the previous two decades.

Instead of following these measured plans that protected the vulnerable until we were sure the health system was ramped up, our leaders panicked and authorised lockdowns, long-term border closures and vaccine mandates.

Therefore, the starting point of any fair dinkum inquiry should be why Australia’s official pandemic plan, reissued as late as August 2019, was effectively junked in early March 2020.

Still, when this Clayton’s inquiry does report, we can at least be confident that any recommendations will be just that; and it will be up to our elected politicians to decide what changes, if any, to implement.

But there can be no such reassurance about the reconsideration of the international pandemic treaty and the international health regulations that’s now under way.

Well below the public radar, this has been taking place since late 2021, with a new treaty and new regulations currently set to be finalised at the end of next month and WHO member states expected to sign up to the new pandemic rules by May next year.

The usual procedure with international instruments of this sort is that Australia ratifies them almost as a matter of course after some cursory scrutiny from a parliamentary committee that has no authority to determine governmental actions.

Yet even though treaty undertakings were once thought not to be legally binding on Australian governments, court decisions from the Franklin Dam case on have shown a readiness to cite treaties in determining what can and can’t be done. So this matters.

The key provision of the new International Health Regulations, currently in draft form, is that “state parties recognise WHO as the guidance and co-ordinating authority of international public health response during a public health Emergency of International Concern and undertake to follow WHO’s recommendations in their international public health response”.

The draft regulations state that health measures the WHO recommends “shall be initiated and completed without delay” and state signatories should “take measures to ensure non-state actors operating in their respective territories comply with such measures”.

As well, each country will be required to establish a “compliance committee” to advise on “compliance with obligations under these regulations” that will “seek the services of experts and advisers, including representatives of NGOs”.

The 46-page draft regulations currently being considered by 194 countries’ negotiators envisage WHO recommendations on proof of vaccination, the requirement for vaccination, the implementation of quarantine, requirements for isolation, contact tracing and movement controls, all of which, presumably, could then become obligatory for WHO member states.

Worryingly, the draft regulations specify that the WHO “shall strengthen capacities … to counter misinformation and disinformation”.

Although both the draft regulations and the draft treaty specify that the WHO won’t infringe national sovereignty, in the end these new instruments mean whatever courts say they do; and our courts, at least in recent times, have taken an expansive view of what international treaties can compel or prohibit.

On the face of it, once the WHO has declared an international health emergency, the plain words read that the Australian government must follow WHO advice, should Australia ratify the new treaty.

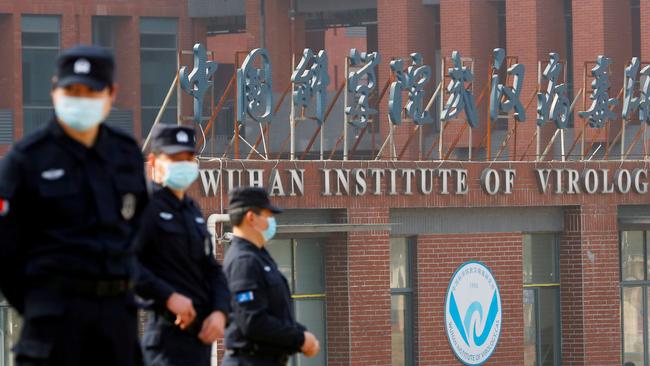

This is the same WHO, headed by a Chinese-backed director-general, that fulsomely praised China’s pandemic response and didn’t contradict Beijing’s initial reassurances that there was no evidence of human-to-human transmission and that the Wuhan outbreak could easily be controlled, even after China had started importing supplies of personal protective equipment on a massive scale. In February 2020, WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus even claimed (somewhat prematurely) that “China’s bold approach … has changed the course of a rapidly escalating and deadly epidemic”. It’s the same WHO that relies for much of its funding on the pharmaceutical companies whose products it heavily backed.

Last month Ramesh Thakur, a former UN assistant secretary-general, said adopting the new pandemic treaty and regulations would “effectively change the WHO from a technical advisory organisation into a supranational public health authority exercising quasi-legislative and executive powers over states”. He said this was the latest manifestation of the rise of an expertocracy and represented the further “transformation of the national security and administrative state into a globalised biosecurity state”.

As well, some US states such as Florida and some countries such as New Zealand and The Netherlands have reportedly raised objections to the scope and reach of these proposed new global pandemic rules.

When some of these concerns were raised in Senate estimates recently, the government dismissed them as far-fetched.

Yet who would have thought, before the pandemic, that Australians would have lived for the best part of two years under a virtual health dictatorship with rigorously policed restrictions that were absolutely unprecedented, even in wartime?

It’s telling that, in its recently released submission to the Covid inquiry, the federal Treasury praised the spending of more than half a trillion dollars (or nearly 30 per cent of GDP) by state and territory governments on the extraordinarily thin grounds that it supposedly meant our post-pandemic recovery “was stronger than expected and more rapid than many other advanced economies”.

To deal with supposedly existential threats that may involve some risk to some people, it seems that almost any measures, however draconian or however extravagant, are now taken to be justified. In this climate, it’s quite likely that countries could sign up to a form of global health dictatorship without giving these new rules the scrutiny they deserve.

That’s why the ramifications of any new global pandemic rules need debate and clarification fast because right now it’s the bureaucrats negotiating with the WHO, not the politicians we elect to take responsibility.

It’s why it’s vital that any federal inquiry not take it for granted that anything goes in the name of safety; and why we still need a full royal commission, rather than the current token inquiry, into the most damaging public health crisis of our time.

More Coverage

To deal with supposedly existential threats that may involve some risk to some people, it seems that almost any measures, however draconian or however extravagant

To deal with supposedly existential threats that may involve some risk to some people, it seems that almost any measures, however draconian or however extravagant

Next month, the World Health Organisation is expected to finalise a new pandemic treaty that, once ratified, would become legally binding on Australia and potentially subject us to even more draconian rules than under Covid.