Curriculum wars cruel the thrill of discovery

But one thing, I would hope, is beyond dispute: An intensive focus on the first half of a century of colonisation (1788-1838) will simultaneously enrich our understanding of Indigenous culture and deepen our knowledge of European traditions.

It’s the period that makes Australian history exciting.

More and more of the history of this crux period is written from an Indigenous point of view, or in an attempt to recover Indigenous history and prehistory and sweep them into the mainstream — where they belong.

University of New South Wales historian Grace Karskens’ 2020 work, People of the River: Lost Worlds of Early Australia, a 600-page history of the Hawkesbury-Nepean river, or Dyarubbin to its inhabitants of more than 50,000 years, is a fine example of this rich new seam in Australian historical narrative.

The book, at once thoroughly researched and engagingly written, explores the “lost world of Aboriginal people and settlers” on that river, and the way its subsequent history was shaped by its geography.

There’s an emotional, excitable tone to sections of the book — a tone of genuine discovery. “The urge to discover secrets is deeply ingrained in human nature,” wrote John Chadwick, one of the decipherers of the Mycenean Greek Linear B scripts.

Karskens’ discoveries are certainly not of that order, but when she writes of being “thunderstruck” after unearthing a catalogue from the colonial era of “Native names of places on the Hawkesbury” — most of the Aboriginal names from the region were believed lost forever — and of her hopes that these names might “come back into common use once more”, we sense the potential of the recovered past to animate the present.

If something of the excitement of discovery can also animate the classroom, well, what’s not to like?

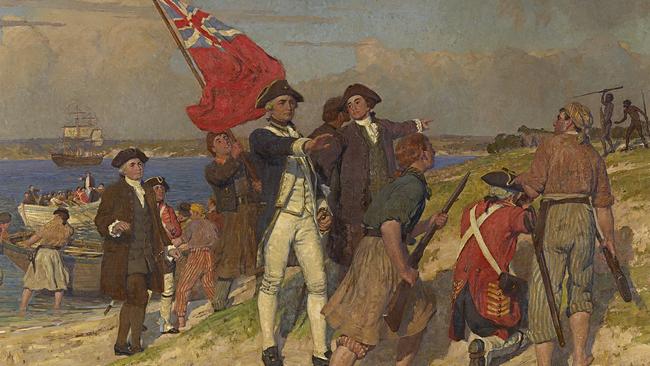

The early Australian colonial period of first contact, settlement and expansion, a period of cultural conflict and high drama — of abiding tragedy for Indigenous culture — is a hinge moment in the history of Western civilisation, and one that compels us to expose and explore its deepest roots: its origins.

That’s another thing that makes a strong focus on the early decades of European history in Australia so compelling. This exceptional period, being thinly documented, is also vulnerable to partisan fancy and mythology.

The future of race relations in this country depends, to some extent, on deepening our knowledge of the first half-century of colonisation to the point where we are able to distinguish readily between folklore and historical fact. The capacity for making distinctions is a hallmark of debate, and healthy debate is an essential part of democratic life.

It’s in this sense that an intensive study of the most dramatic period in our young history also becomes the whetstone on which intelligence and discernment are sharpened at a young age.

The year 1838 marks the end of the Georgian age — the apotheosis of English neoclassicism. And to fully take the measure of the neoclassical you have to first understand the classical well enough to appreciate the connections between the root culture and its revival, but the disconnection too. A strong understanding of this period involves a journey along the new frontiers of Indigenous and early contact history and, at the same time, an inquiry back in time to the Greco-Roman origins that the elite culture of Western Europe was so determined to flaunt and display, to possess — to colonise.

At the level of popular style, the impress of neoclassicism on Georgian culture can be seen in the popularity of women’s costumes based on figures from Greek or Roman myth. These evolved out of the French Revolution to influence women’s dress in Jane Austen’s Regency period. The Prince Regent, for his part, sported a hairstyle — depicted often in portraits and busts — known as the Titus. The hair was worn short and the locks, or those that remained, were pushed forward and piled up.

Of course, the whole vocabulary of Regency architecture — its fixation on Corinthian columns and temple-fronted neo-Palladian mansions — takes its bearings from this recovery of the classical, as does Spode Wedgewood. In Tasmania’s Port Arthur, a supposed hell on Earth, we can detect its traces in the temple front on the powder battery, and the crude loggia beneath it.

I mention here only the superficial visual registers of a powerful moment in European civilisation. The dream of the classical also inspired Shelley’s Hellas, Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn, and Byron’s Isles of Greece.

This was also the age of the Scientific Enlightenment and scientific discovery was the impetus — or at least one impetus — behind James Cook’s first voyage. The primary aim of that voyage of 1770, during which Cook reached the east coast of Australia, was to observe the Transit of Venus in Tahiti. That’s sometimes forgotten. Of course, the Enlightenment is an enormous subject, and a hotly contested one, but it’s all the more interesting for that.

Train a history curriculum on the late 18th- and early 19th-century history of this country and you kill, in a manner of speaking, progressive and conservative birds. The end result is a sharper focus on both Aboriginal and European “perspectives”; on new discoveries as well as traditions and continuities. And it’s something to be excited about.

Luke Slattery is a journalist and author. His latest book is a colonial era fiction titled Mrs M (Fourth Estate).

The 10-week consultation period for the national curriculum review will throw up a variety of responses, one of which was offered last week by historian Geoffrey Blainey (“Curriculum swings the pendulum too far”, 6/5), to the problem of how to weight Indigenous versus European “perspectives”.