It’s only a couple of months since Xi Jinping concluded his report to the Chinese Communist Party’s five-yearly congress by pledging that “we will ensure that the great ship of socialism with Chinese characteristics catches the wind, cuts through the waves, and sails steadily into the future”.

Since he became paramount ruler 10 years ago, Xi has seized full and unquestioned control of the China story. Every challenge – including some exacerbated by Beijing’s own relentless “fighting spirit” – has been met, at least rhetorically, by firm formulas from the top.

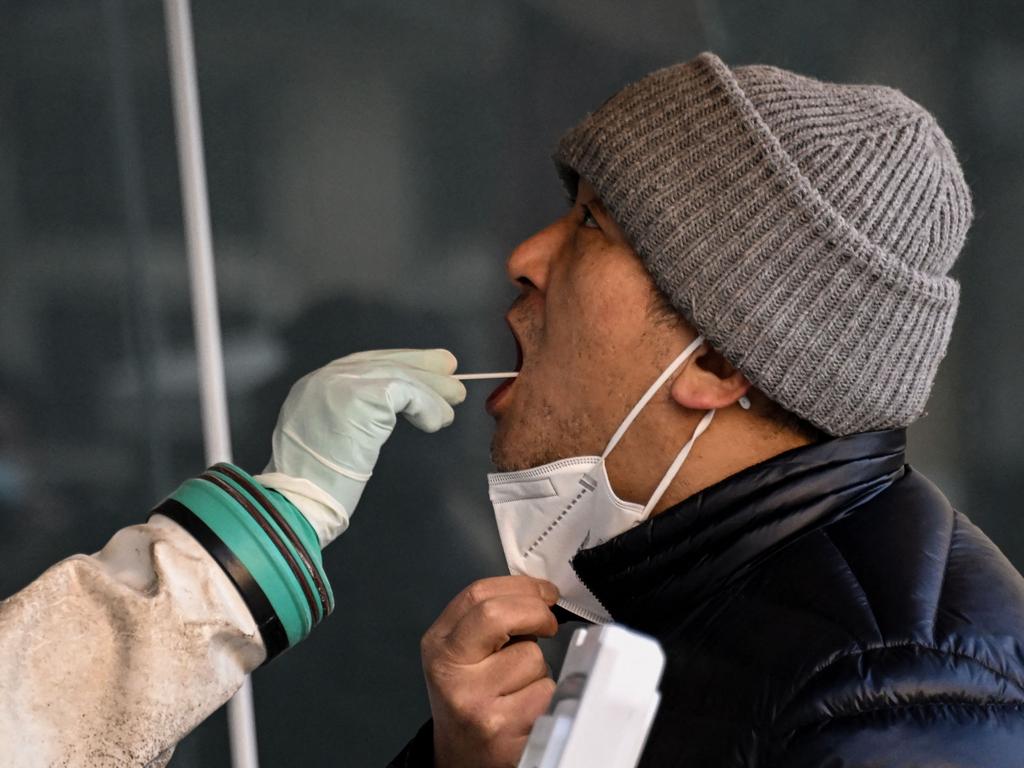

When Covid-19 hit China, the party’s leaders were at first perplexed, but soon enough they found a new narrative – Xi as “the people’s leader” commanding “the people’s war” against the pandemic and winning through severe but necessary lockdowns – and regained their stride.

But now we’re in a rare and increasingly awkward moment of inertia. The party state and especially Xi personally have hit the doldrums. And no one yet knows whether the leadership has any answers or, if so, what they might be.

This is especially problematic since the party has become so centralised and personalised under Xi. Xinhua chief editor Fu Hua has said: “We should never disappear from the sight of General Secretary Xi for one minute.” So what, then, if Xi himself disappears from sight for a while?

The draconian zero-Covid strategy has been abandoned, seemingly both because China has been overwhelmed by the Omicron variant and, as significantly, because the protests at the start of this month indicated that much of the population had lost faith in the effectiveness and the humanity of the “people’s war” approach.

The cruel effects of Omicron are being exacerbated by the low levels of vaccination among the elderly, by the sole reliance on less effective Chinese vaccines and by wider problems in China’s primary healthcare system.

Many people felt they had been pushed beyond the limit of their patience, not only by the seemingly interminable Covid constraints but also by the advances in surveillance and control of their lives that had cut them off from cosmopolitan dreams and by the party pushing of Xi-Thought propaganda into every level of education.

At the same time, and not by coincidence, Xi’s new “common prosperity” economic strategy has run aground. This prioritises the state, drives party committees into the management structures of private companies, and confronts the property sector where most of China holds its savings and the tech sector that holds the most promise for China’s future.

Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Krugman wrote a few days ago in The New York Times that “China’s long-running macro-economic problems seem to be reaching a tipping point. Its economy, despite an awesome history of growth, is wildly unbalanced.”

Massive investments have been deployed in an attempted answer, “but all indications are that investment is running into severely diminishing returns”, Krugman writes. “This isn’t a sustainable state of affairs.”

Australia has grown faster economically than China this year. Many economists have postponed into distant decades the potential date when China’s economy may overtake that of the US, with some now saying it won’t happen this century.

The impacts at home in China include a surge in youth unemployment, reaching 20 per cent. Party legitimacy has hinged in part on an assured continuing rise in prosperity, now fading.

Chinese officials at every level – some of them still silently lamenting the punishment of friends and family members in the continuing “rectification” campaigns against corruption – had become confused by the seemingly contradictory instructions to lock communities down while also boosting economic growth.

Such officials will be wondering what instructions to give in the lead-up to the start of the Year of the Rabbit on January 22. After being held back from important family gatherings during the last couple of Covid years, might people now be freed to travel again? If so, might that dangerously intensify this Covid wave?

As a becalmed Party Central appears to be wavering in its formerly fully confident discourse at home, it is also likely to face a more challenging international context as well – with chief comrade Russia on the back foot, and in this region with key democracies in Malaysia and Fiji opting for leaders who tend to be viewed as pro-West.

New prime ministers Anwar Ibrahim and Sitiveni Rabuka, respectively, are by no means anti-China but they are more likely than their predecessors to lean naturally towards democratic rule-of-law options.

We are not seeing the end of Xi, who is a determined and resilient character, nor of the party to which he has pledged his life. He may yet regain his mojo, grapple down myriad challenges led by Covid and the economy, and push China into an unlikely great leap forward. Such a path is one of endless struggle, a favourite word of Xi’s.

But in the meantime, for many ordinary Chinese people, this is a time when they will instead hope simply to re-assume greater control over their own lives.

Rowan Callick is an industry fellow with Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

The surge in China’s global influence this century has been driven by its economic dynamism and by the vibrancy of its discourse that “the West is declining, the East rising”, and that to stand with China is to position yourself on “the right side of history”.