Coronavirus: There is still some mystery behind all these numbers

On March 16 a team of scientists at Imperial College London published an innocuously titled paper on the impact of “non-pharmaceutical interventions” on the spread of COVID-19.

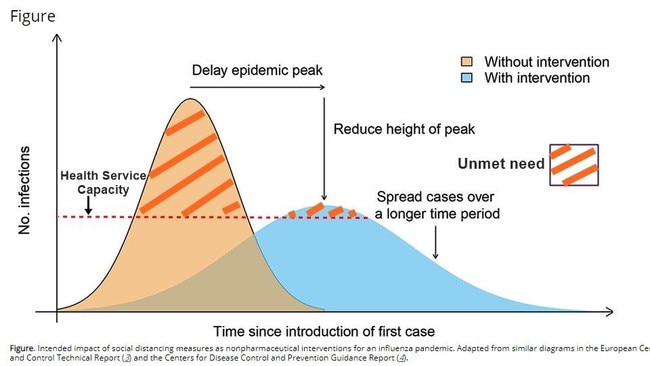

Packed in the paper was a frightening message: if the COVID-19 was just allowed to run its course without check, within weeks it predicted that intensive-care units around the world would be overflowing with patients. The demand would not just exceed capacity, but we would need many times as many ICU beds to meet it.

Within hours the paper made its way through the world, and many credit it for the significant turn in government policy towards the epidemic — leading to an escalation of “social distancing” and redoubled efforts to acquire more ventilators, including rolling out blueprints of ventilators to the likes of Rolls-Royce to get them producing new ones.

How do these papers predict what might happen? They build mathematical models.

Essentially, a series of complex equations that tries to represent events that are happening and might happen. Not just one equation, but several of them in tandem. And they run the numbers over and over again using powerful computers. Each of these models requires one to give the equations some starting numbers, or assumptions, about several aspects: how infectious, how transmissible, how serious, how long a virus lasts. Many of these early assumptions were reasonably derived from the earlier Chinese data.

And therein lies the rub. Even a slight change in these assumptions can often multiply dramatically within an equation and lead to major changes.

A lot has changed in the past few days. More data has become available from China where the problem has been contained, and from Italy, Britain and the US, where it seems to be expanding. To make things even more complex some of China’s data is being reconsidered.

On Sunday, the South China Morning Post newspaper in Hong Kong reported that in addition to the 80,000 cases everyone knows China has, it also had another 43,000 patients who tested positive for the virus but were not called a case because they did not have any symptoms. While precise estimates vary, data from Japan, South Korea and the notorious Diamond Princess cruise liner suggests a significant proportion of the so-called asymptomatic cases could reasonably be expected to be asymptomatic spreaders. If this happens at scale, it is both good and bad.

The good is that it means the virus may not be as dangerous as thought earlier, because many more people have it than we assume. The bad is that if so many can have the virus and not know it, they could easily be going around infecting others and making the job of tracing contacts even more demanding.

This brings us back to models. As reality changes, the structure of these models, and the assumptions built into them, also change. On Tuesday, a group of experts from Oxford University approached the same problem, this time using data from Britain and Italy, allowing for the idea of a large number of asymptomatic cases. And it came to a rather different conclusion: much lower total cases and much lower peak demand for ICUs — the system might just about manage.

Noted British statistician George Box once said: “All models are wrong.” But some models are useful. The Imperial College model drew the world’s attention to the potential magnitude of the disaster. It encouraged governments to work doubly hard on social distancing and reinforcing ICUs — this could only be a good safety measure.

The new Oxford paper opens our eyes to the possibility of a somewhat better outcome — but requires scientists to confirm in what numbers asymptomatic cases exist among us. At the moment, no one knows that answer.

Equations have been very useful in this pandemic, they have helped us think more precisely and have suggested new possibilities.

However, in the end, the equations don’t make decisions for society, our leaders do.

Shitij Kapur is dean of the faculty of medicine, dentistry and health sciences and the assistant vice-chancellor for health at the University of Melbourne. The article expresses his own views and not those of his institution.

Rarely have mathematics and equations been such a matter of life and death for us all.