However, there is one bit of good news. COVID-19 itself is not biological warfare, even accidental biological warfare. There is a pretty virulent conspiracy theory going around to the effect that the pathogen was created, or curated, in China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology — and then deliberately, or accidentally, leaked.

This is wrong.

This possibility has been examined by every relevant scientific and intelligence agency in the West. The Five Eyes, including the relevant Australian agencies, are as sure as you can reasonably be that the virus migrated from bats to humans, perhaps via another animal.

It is, of course, possible that the first human being to contract COVID-19 predates the Wuhan wet market, where it was first detected. It is indeed theoretically possible that someone in a lab was doing some research into a virus and didn’t practise proper hand hygiene. But no one in any of the relevant Western agencies believes this is the case.

It would be insane for the Chinese government to have done this deliberately, and it’s vanishingly unlikely that it did it by accident. The Trump administration is not shy about calling Beijing out for its misdemeanours. And yet no one in the Trump administration is making this charge.

Peter Jennings, of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Australia’s pre-eminent strategic thinker, shares this view. “I think it’s very unlikely that the virus came from a Chinese laboratory,” he says. “There is a history of this family of viruses developing in China. I have no doubt, though, that there is a Chinese biological weapons program, but they’d be working on far more lethal agents than COVID-19.”

Biological weapons are the most secretive program, even more so than nuclear or chemical weapons. The world, broadly speaking, has agreed not to develop or hold them. However, there is a huge amount of research around the edge of these restrictions. There is a legitimate role for Western agencies to look at what potential adversaries are developing. The Russian state has killed people with polonium in London, and tried to kill people with novichok in Salisbury. These are chemical weapons. British intelligence rightly knew a lot about them.

On biological weapons, there are nations that have secret programs in defiance of world bans. The publicly available literature lists those countries as China, Russia, North Korea and Iran. Syria was formerly on the list, but probably its capacities have degraded with constant war.

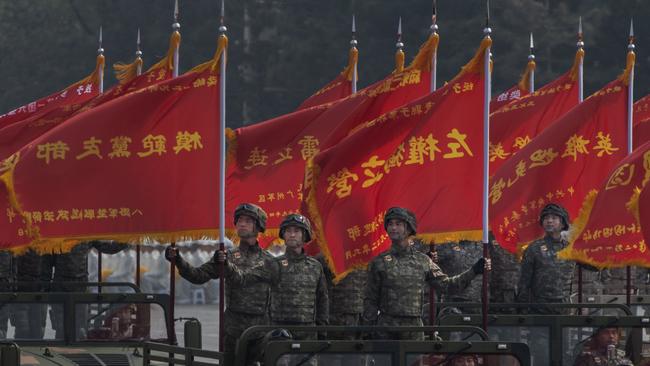

In 2009, the US government issued a report, mandated by congress, that stated Beijing maintained a biological weapons program. The Chinese hotly denied this. And yet Western intelligence is of the view that the Chinese state operates the biggest biological weapons research program in the world.

The COVID-19 crisis demonstrates to everyone — to strategic competitors, ambitious states and indeed terrorists too — the astonishing scale of damage achievable. A virus that has an overall death rate of probably somewhere between 0.5 per cent and 5 per cent has brought the world to a halt. Imagine a virus as easy to catch, but with a death rate of 10 per cent, such as Ebola, or something even worse.

I am not remotely accusing Beijing or any other national government of contemplating the use of biological weapons. But every military and research organisation in the world will have some part of their establishment “weaponising” their thinking about the coronavirus. There is a lot of alarming stuff to think about. The fusion of artificial intelligence, gene technology and offensive biological agents gives a potentially much higher salience to biological weapons.

Apart from common decency, there have been two operational limitations on any nation considering the use of biological weapons. The first is that if they were caught they would likely suffer devastating retaliation. And second, the danger of self-contamination is a big disincentive. This may be changing, with that fusion of AI, gene technology and biology. An article late last year on “Weaponising Biotech: How China’s Military is preparing for a new domain of warfare”, by two well-regarded US researchers, Elsa Kania and Wilson VornDick, brought some of this together.

They comment: “The intersection of biotechnology and artificial intelligence promises unique synergies.” They quote a 2017 book by Zhang Shibo, a former general and president of the National Defence University, which classifies biology as one of the domains of warfare. Zhang wrote: “Modern biotechnology development is gradually showing strong signs characteristic of an offensive capability.”

Zhang further wrote of the possibility of “specific ethnic genetic attacks”. The two Americans also quote another 2017 Chinese publication, The Science of Military Strategy, which talks of “specific ethnic genetic attacks”.

There are a lot of similar examples in Chinese literature. Imagine the reaction if US military publications contemplated “specific ethnic genetic attacks”.

There are some genes, and genetic characteristics, that occur more frequently in one ethnicity than another. Oddly enough, I have a close friend with an extremely minor blood disorder which arises from both parents having a gene that occurs overwhelmingly in caucasian populations. Linking a biological weapon to such a gene might once have been science fiction.

It is no longer science fiction.

Years ago, Beijing made a huge investment in acquiring genetic information. No nation on earth more seamlessly fuses civilian, commercial and military research than does China, which underlines how ill-advised those Australian universities are that continue in joint research projects with mainland Chinese participation in areas such as AI and gene technology.

After the COVID-19 crisis passes, we will still be susceptible to pandemics. The whole world will also be newly susceptible to biological warfare.

The coronavirus crisis reveals the grim and terrible new potential for biological warfare. And the news is almost all bad.