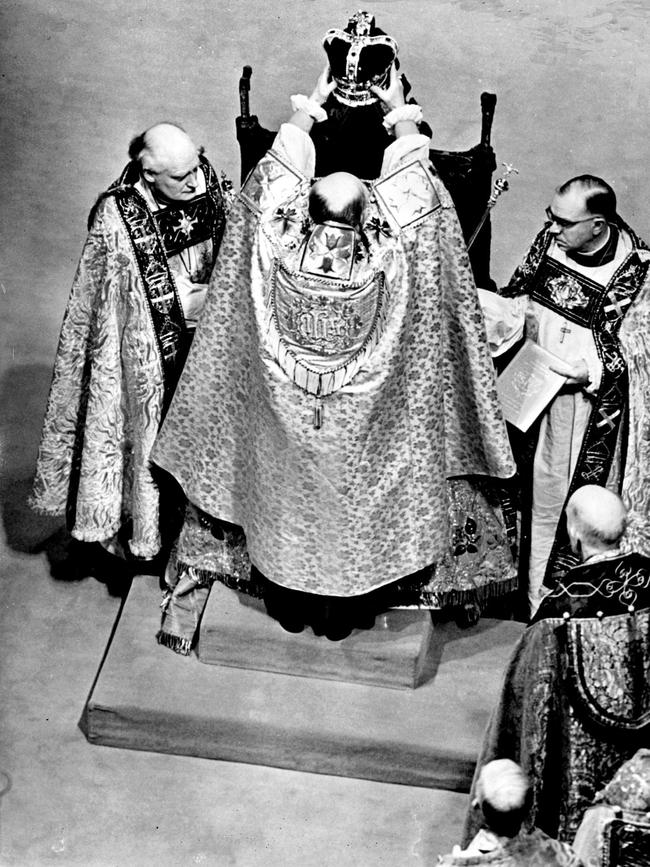

Sixteen years later, when Lilibet was crowned Queen Elizabeth II, that haze of wonder filled a ceremony which, she later recalled, was as drenched in awe and splendour as it was terrifying and exhausting.

Nor were those emotions surprising. An immensely complex religious service, the coronation is rife with symbol and ritual: five swords, four oaths, three chairs, two crowns, spurs, a rod, sceptre and orb, two robes, a golden supertunica and mantle, and many prayers and anthems.

Yet for all of its complexities, and the myriad changes they have experienced, three elements have marked it since its broad form was defined by the Benedictine monk Dunstan who, as Archbishop of Canterbury from 960 to 988, crowned Edgar King of All England, Edward the Martyr, and Aethelred the Ill-Counselled.

The first is the oath by which Edgar bound himself “in the name of the Holy Trinity” to hold “true peace”, “forbid all unrighteous things” and “enjoin in all decrees justice and mercy”.

Immediately the “oath of justice” was given, Dunstan, who had reformed the church and the state according to the Benedictine tradition of duty, prayer and scholarship, warned Edgar – in words that have resonated through the centuries – “if he violate that which was promised God” by “judging unrighteously”, failing “to protect widows, orphans and strangers” or not choosing “old, wise and sober counsellors”, “the end is destruction”.

The second element, hallowing the first, is the liturgy of anointment, which, as in the baptism, initiates the monarch into a new life in Christ, with medieval theology holding that the rite joins the sovereign’s “natural body” to a “body politic” that is divine by grace.

Central to the anointment liturgy is the casting away of the old life, initially by rending the monarch’s shirt, as in the Hebrew Bible’s rite of mourning, and later in the Middle Ages by shrouding the monarch’s robes with a simple white tunic shorn of luxury, the colobium sindonis.

And central too in the anointment is the presence of four swords – the sword of state and the three swords of justice – which reflect the virtues of strength, honour, fidelity and mercy the crown requires to defend the realm and impartially administer justice.

Third and last are the reminders of human mortality in a universe that has survived those who came before and will survive those who come after.

Left empty between coronations, the old and battered Coronation Chair, built in 1297, nearly destroyed in 1916 by a suffragette who hid a homemade bomb behind her feather boa, reminds the monarch his mortal form will die, face eternal judgment and be replaced.

As for the 150-kilo Stone of Scone, which the Coronation Chair houses, it harks back not merely to its legendary origin as the stone that pillowed Jacob’s head when he received the vision of his patrimony, but also to the stones of remembrance that, in the Book of Joshua, symbolise God’s unflagging faithfulness to His covenant and the faithfulness of Israel He demanded in return.

And placing all that in the cosmos is the magnificent pavement on which the anointment and crowning take place. Commissioned by Henry III in 1272, the pavement’s intricate geometry and Latin inscription locate the spot as the “primum mobile”, “the still point of the turning world,” wrote TS Eliot, “where past and future are gathered”, basked in the light and hope of redemption.

It is those three elements – the promise of justice, the gift of grace and the fusing of the here and now into the boundlessness of time and space – which underpin the coronation’s solemnity. But their implications over the millennia stretch far beyond the ceremony itself.

Thus, Fritz Kern, the eminent medievalist, was surely correct when he called Dunstan’s oath of justice “the starting point” of modern liberal constitutionalism, “for it is an explicit binding of the government to the law which is its superior”.

Nor was the anointment any less momentous. Rather, as Ernst Kantorowicz showed in The King’s Two Bodies (1957), undoubtedly the 20th century’s most influential study of medieval law, the fact that the anointment was viewed as making the English monarch a “gemina persona” – a twinned person with divine and temporal natures – was instrumental in ensuring the supremacy of the courts, for it meant that a wrong committed in the monarch’s name could not possibly have been genuinely willed by the monarch, as it would have contradicted his divine nature.

Any breach of the Magna Carta could therefore be overturned by the ordinary courts of common law, as Edward Coke, the Elizabethan era’s towering jurist, held in 1616.

It was to defend that principle and entrench its own sovereignty that parliament updated and extended the oath, and made it obligatory, in the Coronation Oath Act (1688), the Bill of Rights Act (1689) and the Act of Settlement (1701), which are rightly viewed as pillars of British freedom.

That is why William Gladstone – the outstanding 19th-century prime minister and champion of liberalism – thought even “the gorgeous trappings” of the coronation “far less imposing than the profound truth of its idea”.

It is also why Gladstone insisted the “noble and august ceremonial” needed to endure not merely as a way of enthroning the sovereign – whose power was certain to wane in the decades ahead – but also of ritually rededicating the nation to the “profound truth” that links faith and freedom, duty and fidelity, the rule of law and liberty under God.

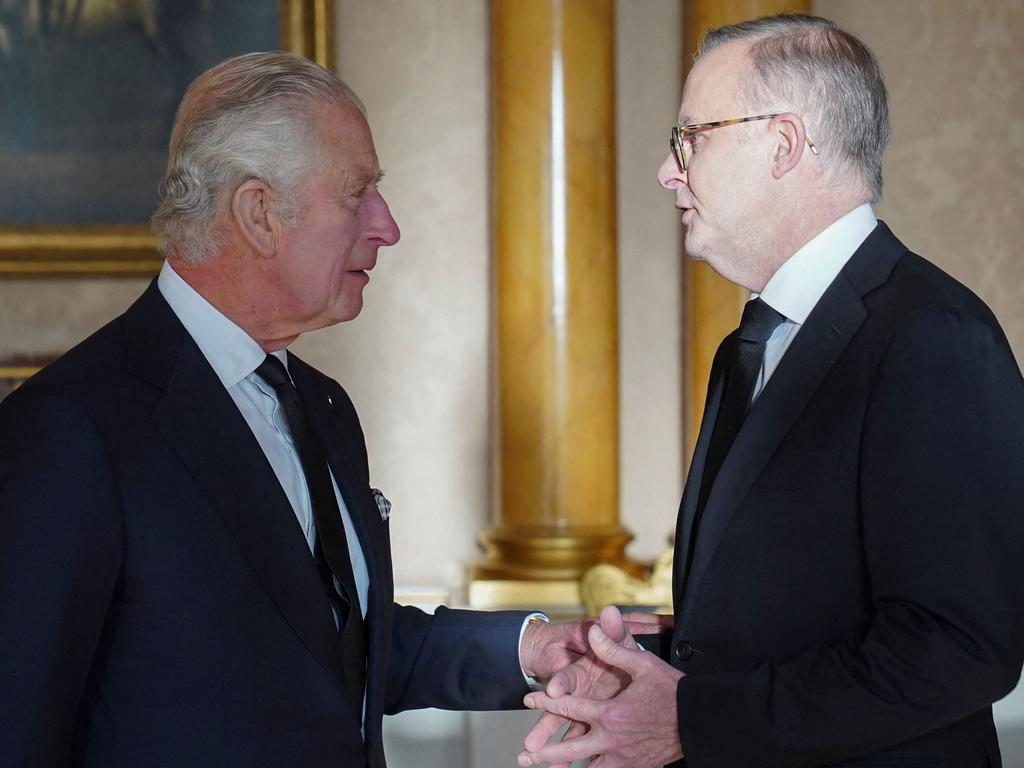

Unfortunately, it is not that truth which will resonate around the world as King Charles III is crowned. Drowned by pomp and pageantry, overshadowed by royal gossip and petty turmoil, scorned by our vocal republicans, spectacle will erase significance. But regardless of the future of our constitutional arrangements, we would do well to remember that Dunstan’s coronation oath is the rock on which Australian democracy was built – and to celebrate the fact that alone in Europe, the oath survived for century upon century, spawning free countries and free peoples around the globe.

And we should remember this too: that in ancient Greek, the antonym of truth, “aletheia”, is not falsehood but forgetfulness, for the truth is what deserves to be preserved from the oblivion of time and the passing of the generations.

Were Lilibet’s “haze of wonder” to fade from memory and lived experience, a part of the history of human freedom would fade with it – and so would a truth which so firmly established that freedom on Australia’s shores.

On May 12, 1937, Lilibet, age 11, wrote to “Mummy and Papa” to say the coronation of George VI had infused Westminster Abbey with a “haze of wonder”.