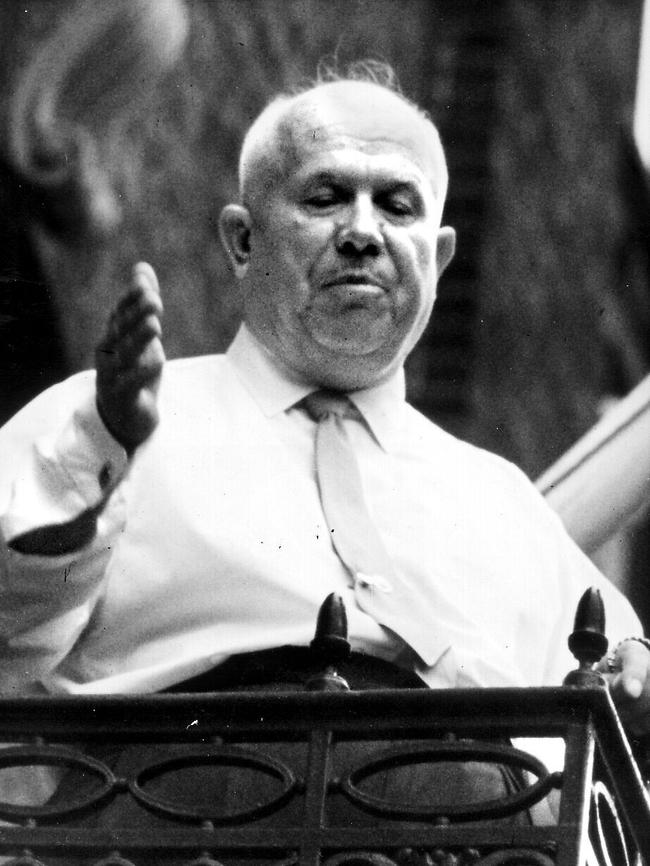

We are living in an era more dangerous than the most tense periods of the Cold War. You can debate the high-octane moments of the Cold War: the Korean War, the Berlin airlift, the Cuban missile crisis, the Vietnam War. But recently obtained Soviet records now reveal that at no time did the Soviet Union seriously plan to go to war directly with the US, nor did Khrushchev or Brezhnev ever seriously want to use nuclear weapons.

Both had lived through the Second World War when the Soviet Union lost an estimated 20 million lives. While they were happy to support their ideological brethren in proxy wars, they understood the horror of total war. They didn’t want that. So during the Cold War there were two dominant powers who were determined to avoid yet another world war. Today there are more than two competing great powers. We don’t live in a bipolar world characterised by two competing ideologies. Today we have a multipolar world. There’s still the US and its allies in Europe and Asia but the other poles are China, Russia and Iran. These countries are less driven by one simple ideology, and more by territorial ambitions and a steely determination to undermine American power and influence.

This is a world more akin to before 1914. Then, as now, there were several great powers divided less by ideology than competing territorial ambitions. Great Britain, Germany, Austria-Hungary, France and Russia all sought to maintain or expand their imperial reach. Before August 1914 no one would have imagined the terrible war that lay ahead. At the Hoover Institution some of the participants thought there was as high as a 40 per cent chance the world of today could spiral into a global war.

How? Let’s start off by looking at the three wars. There is Ukraine, where Russia continues to pour resources into destroying that country’s autonomy. Russia is being assisted directly by Iran, which is supplying it with drones; by North Korea, which has provided a huge amount of ammunition for the Russians; and by China, which, while being careful not to provide weapons as such is nevertheless providing dual-use technologies the Russians are using to fight their war.

What is more, China is sustaining the Russian economy by buying substantial quantities of oil from the Russians, financing the Russian war effort. Although Western sanctions have stopped Russian tankers getting insurance, the Russians have got around this by getting their tankers insured both internally and by China. China, in other words, is party to the sanctions-busting, which is the lifeline of Russia.

Then there is Iran. It is funding and arming Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas in Gaza and the Houthis in Yemen. Iran is using its proxies not just to attack Israel but to try to destroy it. And to finance this war effort, Iran too is selling substantial quantities of oil at a discount price to China. China is a party to breaking the sanctions imposed on Iran by the West.

Then there’s China itself. As it builds up a massive arms capability, it is threatening to subsume Taiwan. It is improbable that China would be able to launch a D-Day-style landing on Taiwan. But it could use the distraction of the wars in the Middle East and Ukraine to throttle Taiwan in other ways. For example, China could claim all ships going to Taiwan should be subject to China’s Customs inspections to try to intercept arms shipments from the US to Taiwan. If it did that, the US would endeavour to stop those inspections and in doing so conflict would erupt. If the US and China came to blows over Taiwan, then all three wars could converge, which they’re starting to do already. And then we’d have a world war.

Iran could conceivably increase pressure on Israel by unleashing a sustained attack by Hezbollah and foment an uprising by the Palestinians in the West Bank. Israel would come under substantial military pressure and the US and its allies would have to provide additional support to Israel and may, in desperation, have to become directly involved in protecting it.

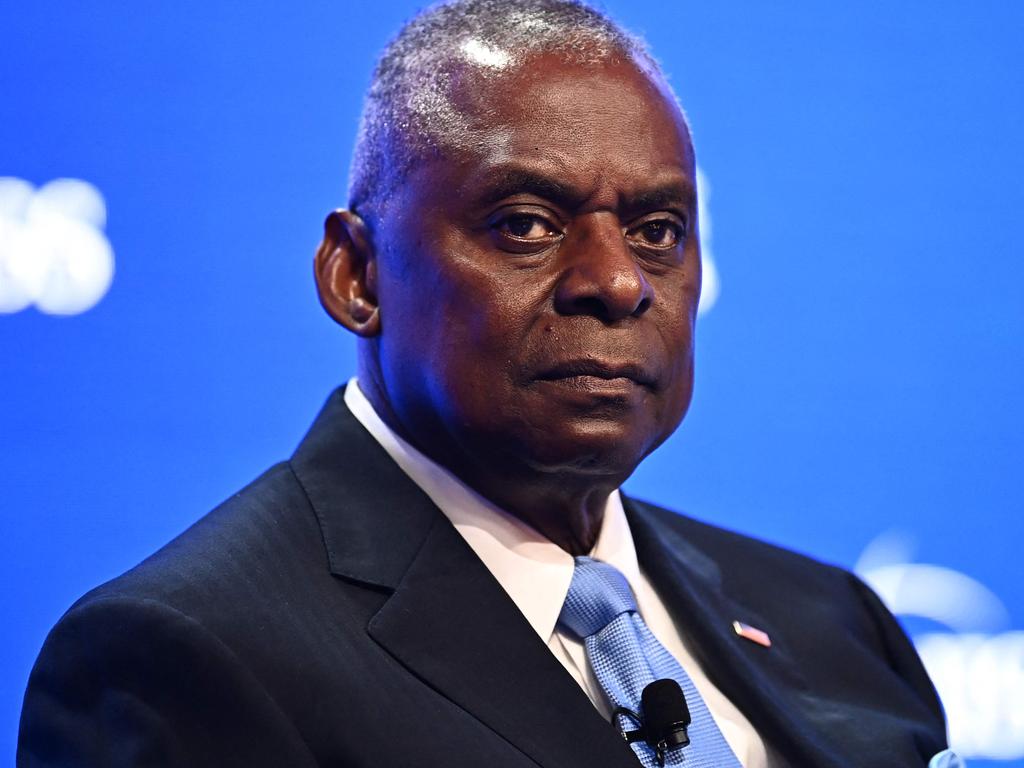

This may not happen, of course, and China in particular may not be so reckless. But you can’t be sure. After all, it may judge the US does not have the will to take the fight to it in the defence of Taiwan. The withdrawal by the Biden administration from Afghanistan almost three years ago triggered a sentiment in Russia, Iran and China that the US is not in the mood to become involved in a substantial conflict.

To avoid these very real risks, the US and its allies must strengthen their determination in three ways. First, the Americans must abandon their caution in supplying weapons to Ukraine and increase the capacity of the Ukrainians to destroy Russian supply lines. The Americans and their allies have to transmit the message that under no circumstances will they allow Russia to prevail in Ukraine.

Secondly, America and its allies must make it clear the behaviour of Hamas is heinous. They have to be unequivocal in support of Israel’s efforts to destroy any military capacity Hamas may have. Of course the Israelis have to dig out the last fighting battalions of Hamas hiding in Rafah.

And thirdly, the US and allies must make it clear China would pay a terrible price, including an economic price, if ever it tried to throttle Taiwan. Living in the calm and prosperous nirvana, the risk of world war seems absurd. It is unlikely, but be realistic, it could happen.

Alexander Downer, foreign minister from 1996-07 and high commissioner to the United Kingdom from 2014-18, has joined The Australian as a regular columnist.

We live in an age of complacency. Since the end of the Cold War we’ve seen living standards steadily rise and we’ve avoided major wars. The great and catastrophic conflicts of the 20th century couldn’t return. Well, they could. Last month the Hoover Institution at Stanford University held a symposium comparing the Cold War with today’s geopolitical environment. The symposium brought together some of America’s leading academics with people who had served in senior political and military roles in various US administrations. Their conclusions were chilling.