Often, but by no means always, these clients are men. And often, but not always, these clients would be seen, at least by some, as “influential and well-respected”. The type who live in Perth’s wealthy western suburbs where a not-for-profit, Deserving Better WA, hopes to set up a “coercive control centre”.

As well as representing those accused of domestic violence I have also engaged with victims of domestic violence, both personally and professionally. I’m not going to pretend I have seen it all, but I’ve certainly seen a lot. It’s clear from the number of women who die at the hands of their partners that something must change. Exactly what those legislative and public spending changes will be is now a central task for our parliamentarians.

Tasmania is the only jurisdiction to have criminalised types of coercive behaviour; however, from July coercive control in current and former intimate partner relationships in NSW will be a criminal offence. Other Australian states and territories are starting to follow, or are considering this.

For some time I have been worried about “bracket creep” in the definition of domestic violence and the way governments and organisations seek to address serious domestic violence in the community. I have always been very cautious, I suspect in part because of my gender, about speaking out.

But the suggestion of a coercive control centre in one of Perth’s most affluent suburbs deserves some critical thought. Because where policy emphasis is placed, what legislation is changed and how we spend money should be a matter for healthy debate. Victim advocates say we need to address the early signs of domestic violence; we’re told non-physical, psychological, emotional and other harder-to-spot forms of abuse often precede and are red flags for the likelihood of more obvious, serious, dangerous forms of domestic violence including physical and sexual abuse. This is certainly backed up by recent research. Again, to be clear, something must change.

But as a criminal defence lawyer I am yet to be convinced the problem will be fixed simply by the ongoing expansion of the definition of domestic violence, or by creating new criminal offences to capture allegations that are, objectively speaking, less serious. Behaviour and actions can be condemned without being criminal.

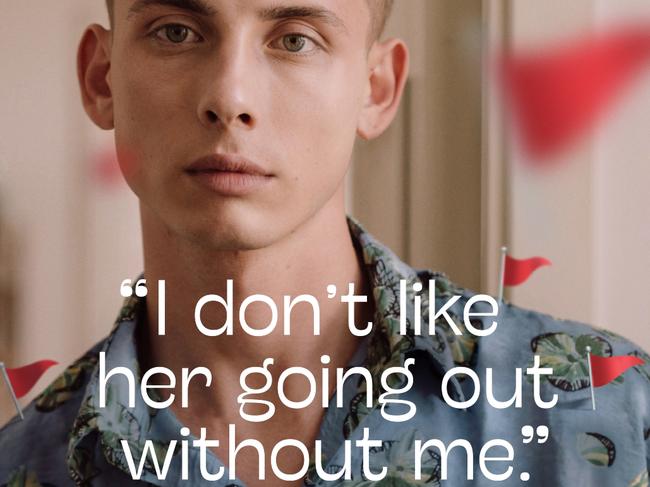

Allegations of coercive control are largely dependent upon a complainant’s subjective assessment of an alleged perpetrator’s behaviour. Increasingly, that assessment is undertaken through the lens of being a domestic violence “survivor”, where the threshold for determining what real-world actions or behaviour constitute “abuse” is, in my observation, descending to dangerously low levels.

Let’s consider a hypothetical victim of coercive control who lives in Perth’s western suburbs. Maybe Peppermint Grove. For those living in Sydney, think Vaucluse. For those in Melbourne, think Toorak. For argument’s sake, the victim is a woman. Her husband has a well-paying corporate job. He works hard. Because of his income, she was able to be a stay-at-home mum, so has not worked for many years. As a sole-income household, is it unreasonable for him to take control of the family finances? No, in my view, although there are limits. She doesn’t require permission to spend money. She contributes to the home and family in different, but equally important, ways.

But if she spends thousands of dollars every month on designer shoes, handbags and eating out with friends, is he not entitled to have an opinion about this, to suggest – or even ask – that she curb the spending? Especially if, for example, increasing mortgage rates and private school fees mean there is less disposable income after the bills are paid? Absolutely.

Let’s further imagine she declines to reduce her spending. Arguments ensue. Voices are raised. The relationship becomes an unhappy one, communication breaks down. To force her spending to reduce, he may take steps to limit her access to family finances.

In the unhappy household, it’s not hard to imagine she may feel she is being controlled. Looked at through a coercive control lens, she sees herself as a victim of domestic violence and starts to believe her husband should be subject to criminal action and punishment. Looked at through a different lens, however, they would probably simply benefit from therapy.

Clearly, in some relationships, boundaries are crossed and the unhappy household leads to a relationship in which serious domestic violence rears its ugly head. But for a majority, seeking guidance from a professional about how to improve the relationship and see things from the other’s point of view would be more productive than apportioning blame and seeking to criminalise behaviour and actions.

One unfortunate outcome of an overemphasis on categorising non-violent actions as domestic violence – worthy of attracting criminal sanction – is that it can detract from the victim of serious domestic violence, the one who likely lives far from Peppermint Grove, Vaucluse or Toorak. Which is why opening a coercive control centre in Perth’s western suburbs will be viewed by some as woefully misguided, warranting some commonsense thinking about where best to focus our efforts, and by others as a simply ridiculous idea.

Karen Espiner is a partner at Hugo Law Group, based in Perth. For domestic violence support contact: 1800 RESPECT 1800 737 732;

Having practised as a criminal defence lawyer for more than 10 years, a big chunk of my time is spent representing clients charged with domestic violence offences.