Early this month, he announced the government’s intention to introduce a New Vehicle Efficiency Standard for Australia. At the time, he told us Australia and Russia are the only advanced economies in the world not to have such a policy.

After the standard is implemented here, Russia will be on its own – something that’s not likely to worry the Russian government unduly. Bowen is targeting a start date of next year.

As is the case with many policy settings, the devil is always in the detail. It’s not just about having or not having an efficiency standard; it’s also about the parameters of the policy, other related measures and timing. Bowen plans to accelerate the implementation of the standard here by insisting we catch up to the US by 2028. This is the first problem with Bowen’s announcement.

How these schemes work is that an overall efficiency standard (typically set in terms of CO2 grams per kilometre) applies across a manufacturer’s entire fleet for sale. On average, the standard must be met, with some vehicles above the standard and others below. Credits are generated if the standard is more than met and these are tradable. For those who cannot meet the standard, these credits can be bought.

In other words, the standard induces price cross-subsidisation so the overall standard can be met and penalties won’t be payable. Electric vehicles are highly prized in this setting. But for those models of cars with above-standard efficiency, prices will inevitably rise.

Now if you think this is suppressing consumer sovereignty, you wouldn’t be wrong. Instead of allowing car buyers to take into account fuel efficiency as well as other characteristics, this policy deliberately restricts consumer choice to meet the government’s target. Bear in mind here that the most popular vehicles in Australia – the Ford Ranger ute and the Toyota HiLux – will massively exceed the new standard. There is speculation of price increases of between $10,000 and $25,000 for some models.

Bowen claims everyone will still be able to buy their preferred car; indeed he expects the choice of vehicles to expand even though Australia is known to be one of the best catered-for markets for right-hand-drive cars in the world.

The fact that there is little demand for some very small, fuel-efficient vehicles – those that are common in Europe and the UK – is mainly due to their unsuitability for families as well as being underpowered for Australian conditions. Bear in mind here that in Europe and the UK, petrol/diesel is highly taxed. The high price of petrol/diesel has been a driving force for many years determining the kinds of cars these citizens purchase. And, of course, many of these countries are the size of a handkerchief compared with Australia.

Using his department’s assumption-driven modelling, Bowen is predicting Australians stand to save about $1000 per vehicle per year by 2028. If that sounds unconvincing, it’s because it is. For starters, most people only buy new cars occasionally.

There are also some large leaps of faith about the take-up of electric vehicles – the real heart of this new policy – and the fact that it should be cheaper to charge a vehicle at home and drive a certain distance compared with filling up an internal combustion engine vehicle. Recent data point to it now being more expensive to use paid-for fast chargers between Melbourne and Sydney than driving a petrol-fuelled car.

(A complication that Bowen chooses to ignore about this policy is the fact that EVs use electricity generated still mainly from coal. The modelling doesn’t take into account this second-round effect.)

Had his department been closely watching overseas developments, he would also have been aware of significant problems emerging in a number of countries in relation to vehicle emissions standards, particularly the US.

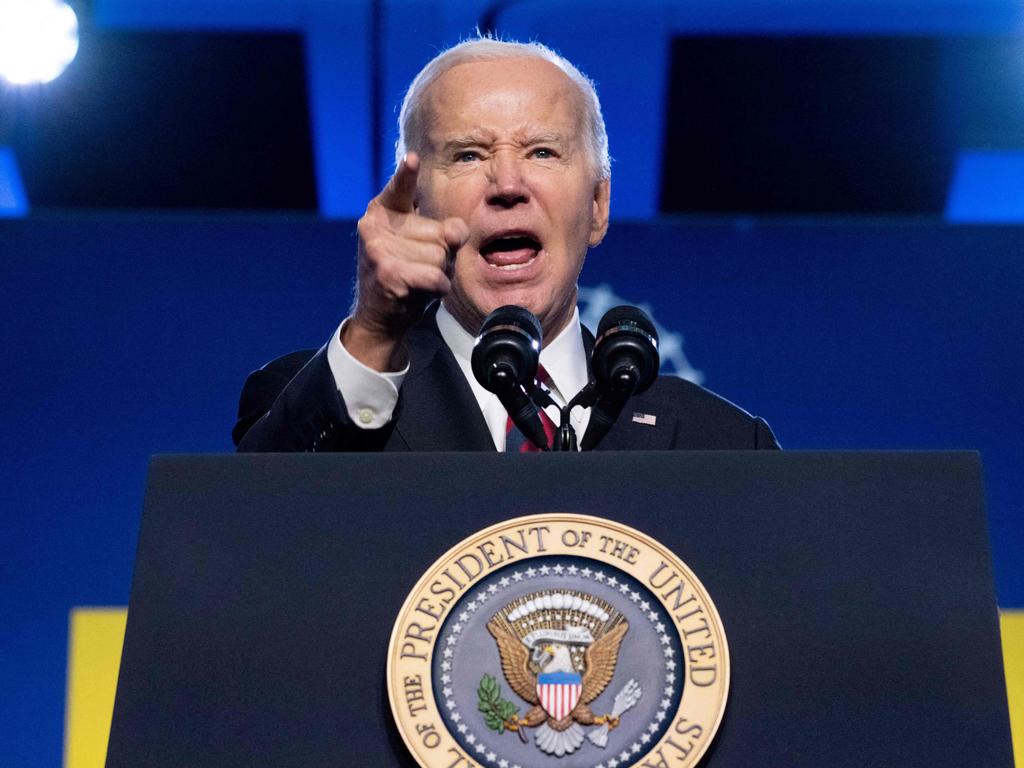

Notwithstanding the extremely generous subsidies available to EV purchasers and the fact that a number of the car manufacturers have aggressively switched to EVs – think here Ford, General Motors and Volkswagen – EV sales have stalled. There are said to be row upon row of unsold EVs in dealers’ premises in the US and the dealers are now loudly complaining. The Biden administration is now considering watering down its emissions standards.

It turns out early adopters were keen to buy EVs – many had another vehicle in their garage – but demand has since slowed. The combination of high purchase prices, costly insurance and poor resale values, as well as ongoing issues with charging, has contributed to this outcome. (In the UK, this trend is, unbelievably, being blamed on an article written by Rowan Atkinson.)

Some of the car companies are now scrambling to change direction, with GM reintroducing a plug-in hybrid model to kickstart sales as well as deal with the efficiency standard. Toyota has emerged a winner in this race, with its chief always sceptical about rapid consumer acceptance of EVs. Toyota has been a substantial investor in hybrid technology and its hybrid vehicles have emerged as commercial winners in a number of countries.

Another clear trend in the motoring world is the increasing dominance of Chinese car manufacturers, particularly in the EV space. Their factories are churning out reasonable quality cars at much lower prices than the car companies that have dominated world sales for decades. Volkswagen, in particular, is under pressure as its strategic tilt to EV production fails to meet commercial expectations. (The fact that Chinese vehicles are constructed using cheap coal-fired electricity is again something that policymakers such as Bowen chose to ignore.)

So what is really driving Bowen’s decision to run with this new vehicle efficiency standard with its accelerated timetable? There are number of factors at work. The first is that some of the car companies and activists have been strongly pushing this standard. Volkswagen, which was caught up in a significant emissions misreporting incident, is very keen to see the new standard implemented.

Secondly, Bowen now realises the government’s stated emissions reduction target of a 43 per cent cut by 2030 won’t be met with current policy settings and the delayed rollout of renewable energy and new transmission lines. He is seeking some quick abatement from road transport to get closer to the target.

As for the conclusion that the policy will return $3 for every $1 spent, pull the other one. I can come up with an equally plausible set of assumptions that leads to a negative net return. When the government report makes the fatuous claim that “the projected impact of (car) emissions on Australian’s climate outlook cannot be ignored”, you know the bureaucrats are talking through their hat. (Hint: it’s about global emissions.)

Bowen might also be well-advised to admit that Australians love their cars.

Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen is not someone who allows the grass to grow under his feet, or under the industrial-sized solar panels he is so keen to promote, for that matter.