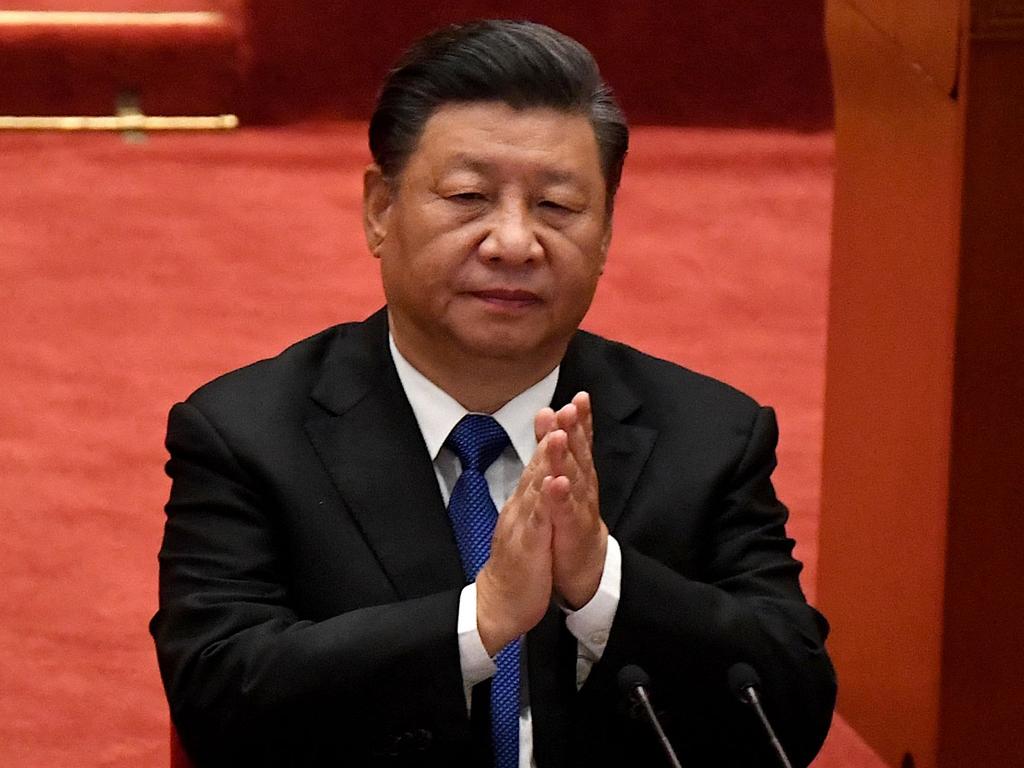

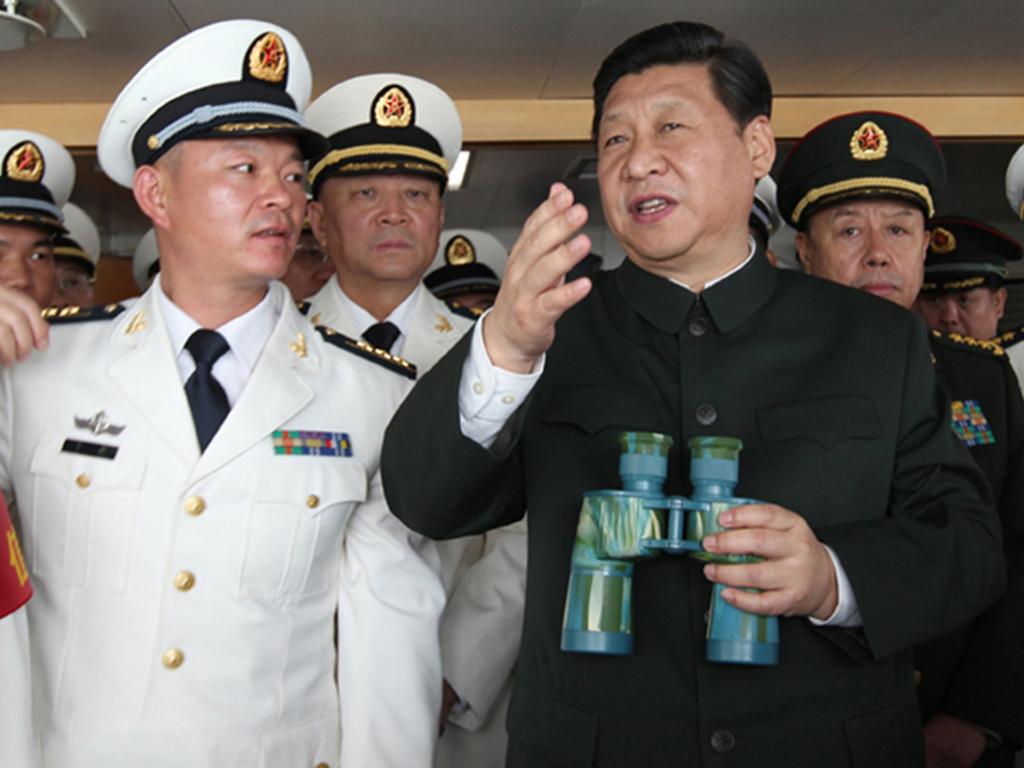

And with the meeting’s resolution on the party’s history mentioning Xi Jinping far more frequently than Mao Zedong (who led the party to power) and Deng Xiaoping (who set China on its road to prosperity), ant-heaps of apparatchiks are presumably hard at work revising the textbooks to reflect Xi’s capacity to “solve difficult problems that were unresolved for many years and to do great things which others had tried to do and failed”.

That is, no doubt, par for the course in communist regimes, which have raised falsifying history into an art form. In part, their incessant fiddling with the past reflects the demands imposed by Marxism: if communism represents the inexorable working out of history’s “iron laws”, the path those laws trace through the past has to be constantly revised to make sure it arrives at today’s triumphant present, wherever that present might be.

Adding to the pressures, each new supreme leader has to be shown to be a legitimate successor to the movement’s patron saints by defining a lineage, stretching back to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, that situates that leader in communism’s forward march. And just as establishing the lineage elevates the latest demi-god into the pantheon, so must everything be scrubbed from the record that might dim the leader’s radiance.

Little wonder, then, that it was Joseph Stalin himself who set the pattern, most notably with his History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks): Short Course, which was first published in 1938, just as the Moscow trials came to their blood-soaked end.

Demonising the “splitters, plotters and spies” who – having been among the revolution’s greatest heroes – had suddenly become the “cringing servants” of imperialism, the Short Course provided a masterclass in historical revisionism.

Nowhere was the Short Course’s impact greater than in China, where Mao – who considered it a “treasure” of Marxism-Leninism – made sure it remained in widespread use long after its removal from the Soviet curriculum. Indeed, so pervasive was its influence that when historian Zheng Yifan was tasked in 1976 with launching a scathing attack on the Gang of Four, he turned to the Short Course’s vitriolic denunciation of Leon Trotsky for inspiration.

But rewriting the past to fit the present also finds deep roots in Chinese culture. Virtually from the outset, compiling histories was not, as it was in the West, mainly the task of independent scholars, motivated by a desire to searchingly examine the past; rather, it was a duty undertaken by official historians.

In a highly bureaucratised polity, their primary function was to gather the administrative decisions, precedents and literary styles that candidates for the mandarinate had to memorise; as Etienne Balazs put it in his famous survey of Chinese historiography, history was written “by bureaucrats for bureaucrats”.

At the same time, however, the official historians “were paid to glorify their masters and vilify the defunct dynasty” their masters had replaced. Tying themselves up in “perilous mental acrobatics” as they tried to reconcile factual accuracy with shameless glorification, their work all too often floundered in “hopelessly confused logical contradictions”.

There were, for sure, some brilliant exceptions. For example, Chinese historiography’s greatest contemporary scholar, Ying-shih Yu, whose works are now banned in China, has shown that by the 4th century BC, Confucius’s guiding principle that one must “transmit what is reliable as reliable and what is doubtful as doubtful” had nurtured a meticulous approach to sources that emerged in the West only many centuries later.

Moreover, Confucius’s oft-cited praise for a historian who, in 605BC, had the courage to record the truth at the risk of his own life — “a good historian”, said Confucius, “his rule was not to conceal” — defined a high moral standard for historical writing.

And it is undeniable that a work such as Ssu-ma Ch’ien’s Records of the Grand Historian, written around 94BC, fully lived up to that standard, evincing an interest in the structural causes of events that was vastly ahead of its time. But despite those exemplars, any flowerings of independent scholarship were suppressed with a ferocity that had no equivalent in Europe’s far more decentralised political system.

Thus, when the Manchu court moved to quell China’s intelligentsia after a virtual renaissance of critical thought in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, it was the historians who were hardest hit because their analyses were viewed as undermining the dynasty’s legitimacy.

Just as historical studies began to flourish in the post-Reformation West – with David Chytraeus’s lectures on Herodotus and Thucydides at the University of Rostock in 1560 and the appointment of Europe’s first full professor of history in 1579 – the decimation of China’s historians precipitated a return to official histories that rarely amounted to more than chronicles and compendia.

However, those episodes of repression pale compared with what was to come with the CCP’s seizure of power. Yet again, a renewal of historical scholarship, which had begun under the impetus of the 19th-century encounter with the West, was brutally terminated, particularly after the 1953-54 campaign to establish Stalin’s Short Course as the primary model of historical analysis.

Some breathing space opened up with Mao’s death; but it proved short-lived, as the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre and then Xi’s 2013 rise to power each brought ruthless crackdowns.

And with this year’s extension of thought control to Hong Kong, the last outpost on the mainland of rigorous historical analysis seems poised to disappear.

Perhaps we should welcome the trend. After all, a society that is afraid of its past can hardly master the great questions it must confront in the present; with its memory gone, it is condemned to flying blind into the future.

But that also makes it liable to be stirred up by concocted hatreds and resentments, encouraging the regime’s propagandists to conjure mythical monsters and imagined grievances out of a history China’s people are not allowed to know.

Nor, it must be said, is our grasp of our own past on so sure a footing as to confidently confront the falsehoods of others. As historical objectivity is attacked throughout the West by those in the schools, universities and media who should be its most zealous guardians, we too risk losing the memory needed to find our bearings.

Tacitus, one of ancient Rome’s greatest historians, once wrote, unforgettably, that peoples are never more surely enslaved than by the lies of which they are themselves the authors.

With historical objectivity everywhere in retreat, today’s lies about the past can only fuel tomorrow’s nightmares.

It was the past, not the future, that changed at last week’s plenary session of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee.