In the weeks after 9/11, Francis Fukuyama defended his influential “end of history” thesis in the wake of the terror attacks, writing in The Australian: “I believe that in the end I remain right: modernity is a powerful freight train that will not be derailed by recent events.”

At home, the Howard government faced a crisis at sea, as the Tampa and children overboard affairs threatened to derail its re-election prospects. In the lead-up to the 2001 election, The Australian broke crucial stories on the unfolding asylum-seeker crisis, branding the government’s response as “reactive, uncoordinated and devoid of any long-term strategic direction”.

Asylum-seekers remained a constant theme into the Rudd years, beginning with the abandonment of the Pacific Solution in 2008. Later that year, journalist John Lyons was dispatched to Canberra to report on Kevin Rudd’s inner circle of advisers, less than a year after Labor’s historic election win. What he found was chaos and dysfunction at the heart of the government.

HISTORY BEYOND THE END

- By Francis Fukuyama. First published October 9, 2001

A stream of commentators has been asserting that the tragedy of September 11 and the ensuing US-led war against terrorism proves that I was utterly wrong to have said more than a decade ago that we had reached the end of history. The chorus began almost immediately, with The Washington Post asserting that history had returned from vacation and Newsweek declaring the end of the end of history.

It is, on the face of it, nonsensical and insulting to the memory of those who died on September 11 and the servicemen who are fighting this new war in Afghanistan to declare that this unprecedented attack did not rise to the level of a historical event.

But the way in which I used the word history, or rather, History, was different; it referred to the progress of mankind over the centuries towards modernity, characterised by institutions such as liberal democracy and capitalism.

My observation, made on the eve of the collapse of communism, was that this evolutionary process did seem to be bringing ever larger parts of the world towards modernity. And if we looked beyond liberal democracy and markets, there was nothing else towards which we could expect to evolve – hence the end of history. Although there were retrograde areas that resisted that process, it was hard to find a viable alternative type of civilisation that people wanted to live in after the discrediting of socialism, monarchy, fascism and other types of authoritarian rule.

This view has been challenged by many people.

I believe that in the end I remain right: modernity is a powerful freight train that will not be derailed by recent events, however painful and unprecedented. Democracy and free markets will continue to expand over time as the dominant organising principles for much of the world. But it is worthwhile thinking about what the true scope of the present challenge is. It has always been my belief that modernity has a cultural basis. Liberal democracy and free markets do not work at all times and everywhere. They work best in societies with certain values whose origins may not be entirely rational. It is not an accident that modern liberal democracy emerged first in the Christian West, since the universalism of democratic rights can be seen in many ways as a secular form of Christian universalism.

The central question raised by critics of this view is whether institutions of modernity such as liberal democracy and free markets will work only in the West or whether there is something broader in their appeal that will allow them to make headway in non-Western societies. I believe there is.

The proof lies in the progress that democracy and free markets have made in regions such as East Asia, Latin America, Orthodox Europe, South Asia and even Africa. Proof lies also in the millions of Third World immigrants who vote with their feet every year to live in Western societies and eventually assimilate to Western values. The flow of people moving in the opposite direction, and the number who want to blow up what they can of the West, is by contrast negligible.

But there does seem to be something about Islam, or at least the fundamentalist versions of Islam that have been dominant in recent years, that makes Muslim societies particularly resistant to modernity.

The answer that politicians East and West have been putting out since September 11 is that those sympathetic with the terrorists are a tiny minority of Muslims and that the vast majority are appalled by what happened. It is important for them to say this to prevent Muslims as a group from becoming targets of hatred. The problem is that dislike and hatred of the US and what it stands for are clearly much more widespread than that.

Certainly the group of people willing to go on suicide missions and actively conspire against the US is tiny. But sympathy may be manifest in nothing more than initial feelings of schadenfreude at the sight of the collapsing towers, an immediate sense of satisfaction that the US was getting what it deserved, to be followed only later by pro forma expressions of disapproval.

We remain at the end of history because there is only one system that will continue to dominate world politics – that of the liberal-democratic West. This does not imply a world free from conflict or the disappearance of culture as a distinguishing characteristic of societies. But the struggle we face is not the clash of several distinct and equal cultures struggling among one another like the great powers of 19th-century Europe.

The clash consists of a series of rearguard actions from societies whose traditional existence is indeed threatened by modernisation. The strength of the backlash reflects the severity of this threat. But time and resources are on the side of modernity, and I see no lack of a will to prevail in the US today.

SCAPEGOATING BOAT PEOPLE

Ahead of the 2001 election, The Australian wrote several editorials critical of the Howard government’s handling of the Tampa affair and the children overboard scandal.

- Editorial. First published November 8, 2001

This election began on the emotion-charged issues of boatpeople and terrorism, and is about to end on the same dangerous territory. Lacking a domestic policy agenda, the government has resorted in the final days of the campaign to desperate scare tactics, again labelling asylum-seekers potential terrorists. But as the claims and counter-claims about border protection reach fever pitch, it is important to return to the basic policy questions. Because Labor certainly isn’t fulfilling its role as a vigorous critic of the government’s unworkable and costly solutions.

John Howard is right on one point. We should decide who comes to this country. But that doesn’t mean Australia must turn back the boats laden with people who have risked their lives to apply for refugee status. As The Australian has argued since the Tampa approached Australia in late August, we can exercise our sovereign right to control our borders, and at the same time treat people with decency. And that means assessing their asylum claims rigorously, fairly and as quickly as possible, on Australian soil, rather than exporting the problem at great cost to poor Pacific nations. We can be hard-headed without treating boatpeople too harshly.

Let’s clear up the deliberate misinformation spread by the politicians who are so bent on winning elections that they distort reality and scapegoat the vulnerable. There is no boatpeople “crisis’’. There are more than 22 million refugees around the globe. Australia, a large, wealthy country with a relatively small population, has an annual quota of 12,000, which we have not yet reached for this year. The numbers coming to Australia are still relatively small, although they have risen in recent months.

The unsustainability of the government’s policy, and Labor’s acquiescence, has caused the liberal wings of both major parties to break out. Julie Bishop has questioned her government’s approach and former Liberal adviser Greg Barns has urged Mr Howard to stop whipping up a frenzy on asylum-seekers. The government refused again yesterday to release the video it claims supports supposed naval reports that the boatpeople threw their children overboard. This was despite The Australian’s report that navy personnel had told Christmas Islanders the allegations were untrue. Is the government telling the truth?

Unfortunately, the critics have chosen to come out at a fairly late stage. If the opposition had displayed more courage during the Tampa crisis, and had more community support, perhaps the government wouldn’t have got its way and we wouldn’t have had to endure an election campaign that has contributed zip to the important issues facing the nation.

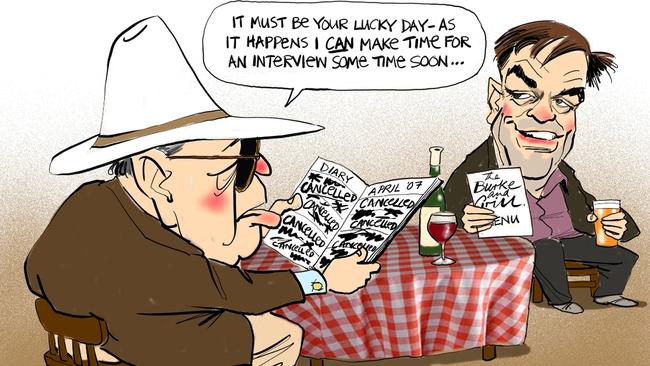

Inside the court of ‘Captain Chaos’

On the morning of June 4, the Prime Minister was sitting in his office in Parliament House transfixed by his television set. The more he watched, the angrier he became: Kevin Rudd was in crisis mode, yet again.

The man, described by someone who had known him for 30 years as having a glass jaw, had yet another crisis: he was angry that in Senate estimates hearings, which he was watching on a monitor, the Labor government was being accused of having broken its election promise to give every secondary school child a computer.

Rudd, being a micromanager, wanted to hear every detail of what the Opposition was saying. What followed was a flurry of meetings and phone calls. Rudd picked up the phone to Julia Gillard, who sits in a nearby office, and asked her to come to his office.

He told the Deputy Prime Minister to get her staff to dig out transcripts of every reference he made during the election campaign about computers. Rudd, with Gillard in the room, then sat analysing every comment he made on the subject.

Whatever meetings Rudd had scheduled were cancelled, once again. Some days Rudd would be sitting at his desk and suddenly begin text-messaging a journalist or editor. One recipient of such texts says: ‘‘It’s part of his private nature. He doesn’t want anyone else to know who he’s having conversations with and this way not even his staff know’.’

The Labor government is six months in power, and chaos and indecision are impinging on decision-making processes. There’s a lot of noise and announcements, but insiders say nothing much is actually happening.

The situation is certainly not terminal: this is a PM who still has a near-record high level of popularity against an Opposition that still has not worked out its longer-term leadership situation.

Rudd is a phenomenon in one sense: he has gone from being an Opposition frontbencher to PM in less than 12 months. But if he keeps governing as he is doing now, he’ll earn the nickname Captain Chaos.

The central problem looks like a chronic lack of experience: there seems to be no one in the PM’s office of the stature or personality to say no to him.

Most PMs have had at least one such person. Bob Hawke had several: Bob Hogg, Peter Barron, Graham Evans, Ross Garnaut, Geoff Walsh, Dennis Richardson and Barrie Cassidy. Paul Keating had Don Russell. John Howard had Arthur Sinodinos.

One top aide, David Epstein, is the invisible man. One of the country’s most influential journalists who works in Parliament House says he has not seen Epstein for two months. Another, Alister Jordan, rarely leaves the PM’s suite. Press secretary Lachlan Harris occasionally — and briefly — swings through the gallery to speak to chosen journalists. Harris is combative by nature and has alienated not just the journalists he is meant to be working with, but senior members of his own side.

It’s said Rudd’s cabinet meetings are often rambling. Sources say ministers often speak at length with little point. After six months in office, the Rudd machine is taking form, and the kitchen cabinet is finding it cannot deal with every crisis.

In effect, Rudd has established a command and control centre, which he runs. Little happens without his approval and ministers are clearly reluctant to make decisions unless Rudd has signed off on them. The two words most commonly used about Rudd’s office are chaotic and dysfunctional.

Rudd’s chairmanship is being contrasted with that of Hawke and Howard. Hawke knew how to run a meeting from his days at the ACTU and Howard was famous for allowing ministers to speak, but if he sensed an idea was going nowhere, he’d cut them off. The way the office is functioning is beginning to lead to questions about the sort of employer Rudd is.

The Prime Minister has an angry public service, an increasingly alienated media, and a chief of staff who, more than likely, will have to call in more witnesses as his wife’s clients chase what they’re paying big money for: to influence the people in the government who make the decisions.

‘BELOW THE BELT’ IN PARLIAMENT

Despite everyone in Canberra promising to raise parliamentary standards, four Labor MPs were booted out of question time yesterday, Tony Abbott was goaded about an illegitimate child and the Employment Minister went perilously close to mocking Mark Latham’s manhood.

Much of the blame for the crankiness this budget session rests with the Speaker. A series of shocking rulings by Neil Andrew in the past week has undermined his authority and encouraged rabbledom. There’s a knack to appearing non-biased while looking after your mates. Andrew doesn’t have it.If he were refereeing at the World Cup, Tokyo and Seoul would be declaring a state of emergency. Abbott really gets up Labor’s nose, especially when the government’s bovver boy lambasts MPs over their union links.

While Andrew has been harsh on opposition interjections, he gives Abbott enormous licence. Naturally, this gets Labor MPs even angrier, and before long the place is in uproar. Latham has been assigned a tagging role for Abbott, and subtlety isn’t one of the maverick MP’s specialties. As Abbott berated Labor’s relationship with the unions, he copped this back: “You’ve had too many unions, Tony, you grub.’’ Confused? Latham reckons Abbott’s attacks warrant a reminder of the child the minister has admitted giving up for adoption in the 1970s. It’s fortunate Abbott and Latham both seem uninsultable.

The minister twisted Latham’s plea for Labor to “muscle up’’ against the government into a call for the opposition to undergo “testosterone enhancement therapy’’.

Simon Crean jumped in as well. As Abbott railed about Labor’s “dirty little secret’’ – alleged subservience to the unions – the Opposition Leader shot back: “What’s your dirty little secret?’’

Abbott seemed happy for others to make the link with the loss of one of Latham’s testicles to cancer.

It’s no great secret – Latham has spoken publicly about his health scare on several occasions – but from the reaction of many Labor MPs, they thought Abbott’s retort was below the belt.

If Latham was upset, he didn’t show it. By the end of questions, he, Tanya Plibersek, Julia Irwin and Warren Snowden had all been ejected from the house by Andrew.

Kim Beazley – whom the Coalition always insisted was deficient in another crucial part of the anatomy – seethed at the back, especially when Abbott labelled him “Plugger’’ because of unfounded rumours of a Labor leadership comeback.

“This is simply debauching question time,” roared the ex-leader. He had a point.

Reader’s view

PROPELLER-HEADS

When I woke up this morning the lights came on, the water was running, the VCR took a program, the computer booted up and the cat still meowed. Chalk one up (or down) for the propeller-heads and their Y2K bug theories.

Tony Clarke, Wentworthville, NSW, JANUARY 3, 2000

A PERFECT LEAD

John Howard has had a perfect lead-up to an election campaign: asylum-seekers, the Tampa, the terrorist attacks, CHOGM threatened and possibly postponed. Perhaps the Labor Party doesn’t need spin doctors – they need fortune tellers.

Ross Brinkworth, Indooroopilly, Qld, September 28, 2001

NICE ONE, JOHN

I don’t think I have agreed with one word that Howard has uttered since he became prime minister but, on the tsunami aid issue, he has finally got it right. If he keeps this up, I might have to reconsider Liberals.

Jacqui Wright, Forrestfield, WA, January 10, 2005

COMPULSORY READING

It is interesting to know that 10,000 Chinese are expected to read a recently translated published biography of our leader Kevin Rudd. I am waiting to read the thoughts of Kevin Rudd should they be printed. Perhaps it should be compulsory reading for all school children and be read at school assemblies and recognition should be given to students who memorise the most of our leader’s thoughts. Indeed it might soon be made compulsory for all 21 million Australians.

Andrew Frederick, Caulfield, Vic, February 4, 2008

OUR NEW G-G

I am neither enamoured of the constitutional requirement for a governor-general nor of the appointment of an ex-military man, but at least we should be grateful that even the Libs wouldn’t dare recommend to the Queen the appointment of another Pom. We’ve come a long way.

Roy Scaife, Australind, WA, JUNE 26, 2003

A new era was born on the morning of September 11, 2001, when two commercial jets emerged from a cloudless New York sky and sliced into the World Trade Centre, striking at the very heart of American power and prosperity. The symbolism was undeniable. Under the smouldering ruins of Upper Manhattan passed the early optimism of the new millennium, extinguished in an instant by the Islamist hijackers who carried out the attacks.