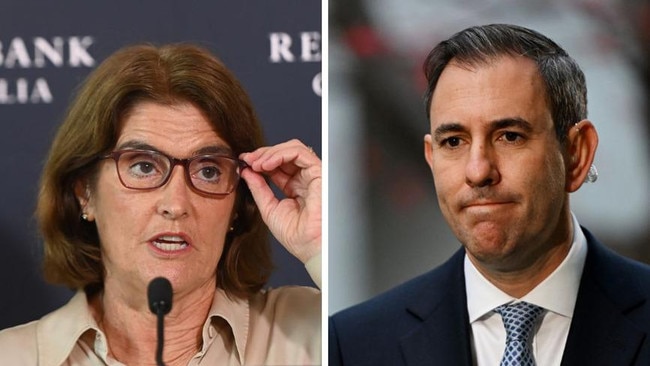

Chalmers has become the ‘brawler statesman’. Now it’s time Bullock pushed back.

In the June quarter, our GDP rose by only 0.2 per cent. Our annual economic growth rate has fallen to 1 per cent, a result we have not seen in more than 30 years, leaving aside the pandemic.

While household spending rose by just 0.5 per cent in the year to June, recurrent government spending was up by 4.7 per cent. GDP per capita has fallen in each of the past six quarters.

This has been described by many as a recession, but that is not the right term.

In classic recessions – including those we had in the 1980s and ’90s – aggregate demand and employment fall off a cliff, resulting in mass unemployment, a tsunami of business failures and financial market panic. Today, in contrast, unemployment remains at close to historical lows and our sharemarkets remain buoyant (if volatile). While it’s true business insolvencies are rising, many parts of the corporate sector remain profitable.

When growth slows to a crawl yet labour and capital remain fully employed, we are experiencing a supply crunch. In other words, a productivity crisis. Jim Chalmers talks about private demand being weak, which is true, but the economy’s productive capacity is weaker still, a reality he is conspicuously ignoring. As James Carville might have said: “It’s the supply side, stupid.”

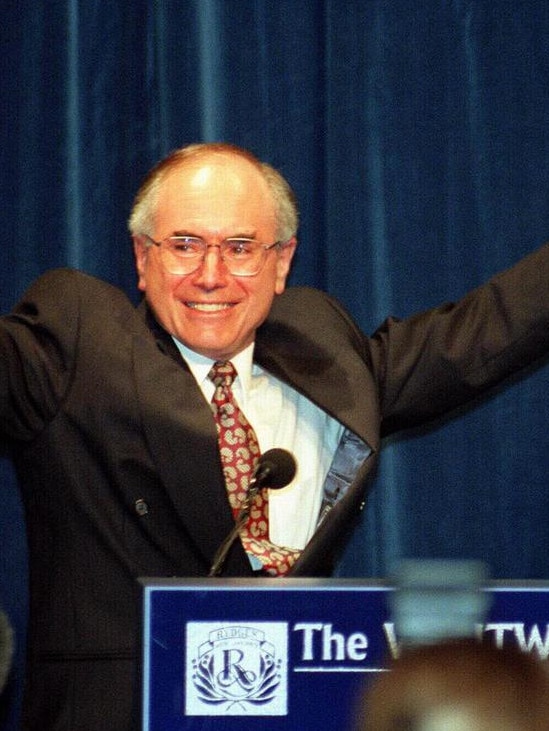

This full employment stagflation is political poison, which is why Chalmers has decided to shirt-front the RBA in recent days, accusing it of “smashing” the economy. John Howard, writing in these pages on Wednesday, was right. Chalmers’ crude attack on the RBA only diminishes him.

After all, Chalmers’ fingerprints are all over the RBA board. Governor Michele Bullock and deputy governor Andrew Hauser were appointed by the government on his recommendation, as were two other recent board appointees.

Chalmers’ chief economic adviser and close confidant, Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy, is also a full voting member of this body and by far the most influential person on it apart from Bullock. (While Kennedy cannot be directed by Chalmers and is nominally independent, I would be surprised if his view on inflation differed much from his boss’s.)

Bullock and her board have been highly sensitive to the government’s desire to protect our post-pandemic employment gains. Some would say they’ve bent over backwards to please it.

In stark contrast to our peer central banks, including the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, which hiked their official rates into the fives to bring down inflation more quickly, the RBA board – notwithstanding the 13 consecutive rate increases it approved – has been reluctant to take the cash rate beyond 4.35 per cent.

It has tolerated inflation being higher and longer in Australia – and risked a breakout of inflationary expectations – to honour the full employment part of its mandate. Yet Chalmers, knowing full well what the bank is trying to do, accuses it of smashing the economy.

Let’s also not forget how diplomatic Bullock has been towards the government. When Chalmers and Albanese objected to the RBA’s recent factual observation (in its statement on monetary policy) that government spending was adding to demand in the economy, Bullock was quick – perhaps too quick – to appease them, telling a parliamentary committee that public demand was “not the main game” on inflation.

If Chalmers took his responsibilities more seriously – and were a cannier politician – he would’ve acted on the RBA’s initial warning, calling on his state counterparts to tighten their fiscal belts and promising that Canberra would do the same. But instead he chose the soft option of shooting the messenger.

To adapt Milton Friedman’s famous phrase, inflation is “always and everywhere” a political (as well as a monetary) phenomenon: a sure sign of a lack of political will and economic policy failure.

If Chalmers really wanted lower interest rates and inflation, he could help bring that result about. Not by browbeating Bullock but by judiciously cutting (or at least pausing) federal government spending and doing more to unlock the supply side of the economy – hitting the pause button on the government’s renewable energy crusade and reversing its retrograde industrial relations changes would be a good start.

I dare say this would be statesmanlike but, instead of the brawler-statesman (the term Chalmers coined for Paul Keating), we are left only with the brawler, and a much diminished one at that.

If anything, this latest episode is worse than a case of boorish behaviour from Chalmers. By so egregiously evading his responsibility for managing the economy, he has – in effect – abdicated the position of treasurer. History shows that when prime ministers allow this to happen, they and their parliamentary colleagues pay a heavy political price.

David Pearl is a former Treasury assistant secretary.

As expected, Wednesday’s national accounts confirmed that the economy has ground to a virtual halt.