Building Australia’s future: Tackling challenges of declining fertility rates

Australia’s fertility rate has been on a steady decline, and the latest ABS Births data for 2023 reveals a continuation of this trend. In the past decade, Australia’s total fertility rate decreased significantly from 1.88 to 1.5. These figures stand well below the replacement rate of 2.1 children per woman.

Australia is on par with many developed nations that have recorded similar declines due to social and economic shifts. Countries like Japan, Italy, and South Korea have had similar or even more drastic declines, such as South Korea, which reached a fertility rate as low as 0.78 children per woman in recent years.

While Australia’s situation isn’t as extreme, the implications for our future workforce, economy, and society are substantial. Understanding where we stand in comparison to other countries can provide valuable context as policymakers and citizens grapple with the potential impact of these demographic shifts.

The rising cost of housing, particularly in metropolitan areas, has become a notable barrier for young adults considering starting families. As housing costs continue to surge in our capital cities, especially in Sydney and Melbourne, younger Australians face difficult choices between homeownership and raising children.

Furthermore, Australian parents often bear a heavy financial burden when it comes to childcare, making family life a challenging endeavour for dual-income households. These pressures contribute to the trend of smaller families or delayed child-bearing, with a growing preference for one-child families or no children at all.

The consequences of Australia’s declining fertility rate are particularly pronounced in the property sector. In the past, demand for housing has been heavily influenced by natural population growth, with new families seeking homes in suburban and regional areas.

However, as fewer children are being born, the demand dynamics for family-sized homes may shift over time, particularly in areas where birthrates are declining most sharply.

The traditional “Australian dream” of a family home on a quarter-acre block may become less achievable, not only due to housing affordability issues but also because fewer families might be looking for these kinds of homes in the future. In high-density urban areas where young professionals are delaying family life, there may be increased demand for smaller apartments and units rather than larger family homes.

This trend may prompt the property sector to rethink its future development plans and consider the evolving needs of a society where smaller households are more common.

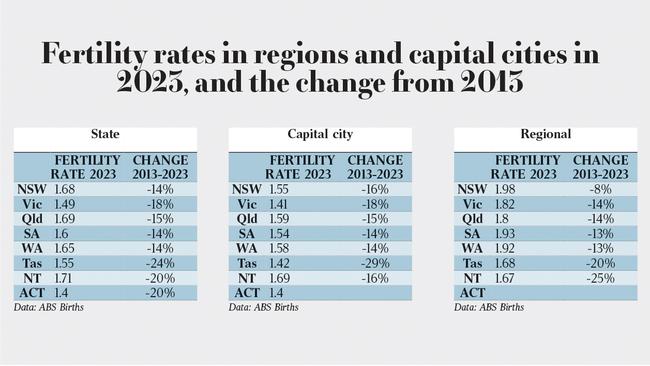

At a state and territory level, ABS data shows significant variation in fertility trends, underscoring the impact of local economic conditions and lifestyle preferences.

NSW has the second-highest fertility rate (1.68) among the states after the Northern Territory (1.71). Compared to 2013, the fertility rate in NSW decreased by 14 per cent.

However, there is a clear distinction between regional and metropolitan NSW. Regional NSW has the highest fertility rate among regions at 1.98 births per woman, while Greater Sydney stands at 1.55 births per woman.

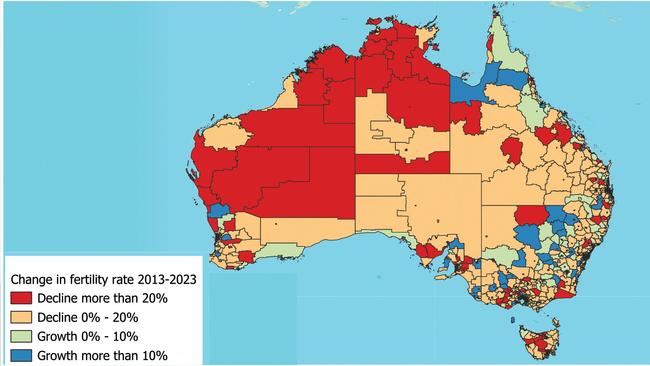

At a suburban level, many suburbs in regional NSW experienced an increase in fertility rate. In Gilgandra, the fertility rate increased by 31 per cent from 2.77 in 2013 to 3.62 in 2023. Similarly, Culburra Beach increased by 25 per cent from 2.04 to 2.56 in the same period.

Fertility rates are higher in Gilgandra due to its affordable living, family-oriented culture, and younger, family-focused population compared to urban areas. According to 2021 census data, the median rent in Gilgandra is about $200 per week, which is well below the national average of $375 per week.

Victoria recorded the lowest fertility rate among all states at 1.49 births per woman. Compared to 2013, this figure had massively dropped by 32 per cent. Victoria follows a similar trend as NSW with regional fertility rates sitting at 1.82 compared to Greater Melbourne at 1.41 births per woman.

Suburbs in the inner and middle rings of Sydney and Melbourne, such as Burwood in Sydney or Box Hill in Melbourne, recorded substantial drops in birthrates – falling by 46 per cent and 49 per cent respectively between 2013–2023.

This can be attributed to the younger, more transient, and career-focused populations who often rent rather than own, reflecting a shift toward urban living.

For these residents, housing affordability and the high cost of raising children in city centres create powerful incentives to delay or forgo parenthood.

In contrast, regions on the outskirts of major cities and in certain regional centres are showing more resilience in birthrates. For example, areas like western Sydney, Geelong in Victoria, and the Gold Coast in Queensland have recorded a more moderate decline or, in some cases, a slight increase in fertility rates.

These regions typically offer more affordable housing options and a slower pace of life, which may be more conducive to family formation. The growth of infrastructure in these areas, including schools, parks, and recreational facilities, makes them attractive for young families seeking an alternative to metropolitan living.

This shift also aligns with the increased trend toward remote work, which allows professionals to live further from city centres without sacrificing career prospects. The property sector in these regions may see a sustained demand for family homes, which could drive local development and infrastructure projects.

In Queensland, coastal areas such as the Sunshine Coast and Cairns continue to attract young families, in part due to the lower cost of living and lifestyle appeal of coastal living.

Queensland’s overall fertility rate (1.99) is slightly higher than the national average, and local councils are likely to consider this demographic strength when planning for community services and housing developments.

In WA and SA there is a similar pattern, with regional areas having slightly higher fertility rates compared to their city counterparts. Both regions experienced a drop of about 14 per cent in metropolitan areas and 13 per cent drop in regional areas between 2013-2023.

While Tasmania and the NT also exhibit declining fertility rates, they show unique trends. Tasmania’s ageing population and limited migration mean that population growth has historically relied on natural increase.

Tasmania had the highest drop in fertility rate among all states at 24 per cent during the 10 years to 2023. Declining fertility rates here could accelerate the demographic challenges faced by an ageing population and smaller workforce.

The NT, on the other hand, maintained a relatively higher fertility rate compared to other states, in part due to the younger population and high birth rates among Indigenous communities.

However, recent declines (2.13 in 2013 to 1.71 in 2023) indicate that even the Territory is not immune to the broader national trend, and the economic challenges faced by remote communities may contribute to future shifts in family formation patterns.

These declining fertility trends raise critical questions about Australia’s long-term demographic and economic future. A lower birthrate means that natural population growth will play a diminishing role in offsetting the impact of an ageing population, putting increased pressure on migration to sustain the workforce and maintain economic productivity.

This reliance on migration as a population driver, while beneficial, introduces its own complexities, such as integration challenges and infrastructure demands.

Furthermore, the changing age structure will place greater demands on health and aged care services, creating new policy imperatives to support an ageing population with fewer young people contributing to the tax base.

For the property sector, the implications of a declining fertility rate could be profound. Developers may need to shift their focus from family-oriented housing toward more diverse offerings that cater to singles, couples without children, and older residents looking to downsize.

The growing preference for inner-city living among younger Australians could boost demand for apartments and smaller dwellings, while outer suburban and regional areas may continue to attract families looking for affordability and space.

This shift will likely influence not only residential real estate but also the broader infrastructure planning, as communities will require different amenities based on their changing demographic profiles.

To improve fertility rates in Australia, policies that support family formation and reduce the cost of raising children are essential.

Countries like France and Sweden offer valuable examples: both have introduced generous parental leave, subsidised childcare, and family allowances, which have helped them maintain higher fertility rates compared to other European nations.

France’s fertility rate, for instance, remains close to 1.8 children per woman due to policies that make it easier for parents to balance work and family life.

Australia could adopt similar measures, particularly targeting housing affordability and child-related costs.

Regional areas with lower housing costs and family-friendly amenities provide a supportive environment for raising children, and additional investment in infrastructure and services in these areas could encourage more families to move there. Ultimately, understanding the regional variations within fertility trends offers a road map for tailored responses.

By aligning housing, childcare, and workplace policies with the needs of young families, Australia can build communities that support both economic growth and family formation.

The conversation on fertility and family formation in Australia is not just about numbers; it’s about rethinking the social and economic framework that will support generations to come.

Hari Hara Priya Kannan is Data Scientist at The Demographics Group

Around the world, falling fertility rates are often driven by common factors such as people choosing to start families later in life, more women pursuing higher education and careers, and a shift toward urban living.