Bloodstained history belies Beijing’s push for a friendly global image

Of course, the China question is a sensitive one for Australia. Geography dictates that how Canberra handles an economic superpower guided by “Marxist-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought” — to quote Xi Jinping — is a matter of practice rather than theory.

Australia walks a tightrope: be too hard on China and it risks economic damage; be too soft on China and it might risk strategic suicide. The notoriously thin-skinned Chinese Communist Party reacted to Hastie’s comments by denouncing him. Its embassy in Canberra accused Hastie of having “Cold War thinking” and displaying an “ideological bias”. All of this is an effort to protect the positive global image of China that the CCP has invested billions in shaping during the past decade.

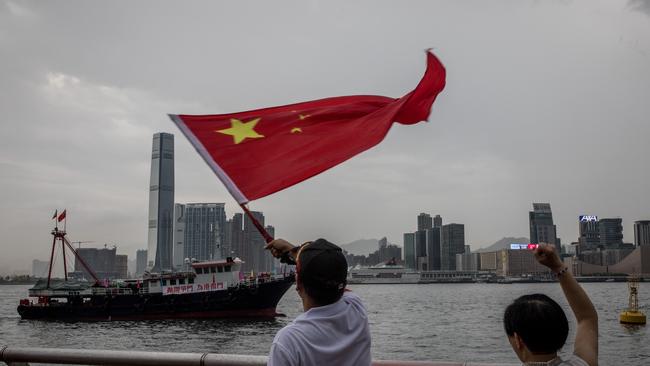

The image that Beijing has been promoting is that China’s rise is peaceful and does not present a threat to the world.

It does not include the more than one million Chinese Muslims incarcerated in Xinjiang on account of their faith.

Nor the estimated 45 million people who starved in the blood-soaked Great Leap Forward between 1958 and 1962, or the up to two million people who died in the so-called Cultural Revolution between 1966 and 1976.

It also does not include recognition of the independence of Taiwan, which is a beacon of democracy, freedom and the rule of law. One of the CCP’s key propaganda claims is that it has raised hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, but Taiwan’s gross domestic product per capita is three times China’s.

The CCP’s leadership has a long-term plan to win what it sees as the country’s rightful place as the world’s biggest and most powerful country. Hastie is realistic enough to know what this means. Australia, like the West as a whole, benefits from the rules-based international order, or at least what is left of it. China regards it as unfair and plays successful divide-and-rule games to undermine it. As Beijing pursues its plan, the West will have to make a choice: tolerate China’s behaviour or oppose it.

Proponents of the former approach argue that as China grows wealthier it will become a fully fledged member of the international community as it will have more to lose than if it does not. The post-Cold War period suggests the opposite. At home, the CCP has used its riches to pursue greater state power at the expense of greater state openness. Abroad, revisionism rather than reconciliation drives Beijing’s behaviour.

Hastie’s comments had particular resonance in London. It was here, in June, that the text was first delivered as a speech at a closed-door conference hosted by the Henry Jackson Society, an international affairs think tank, and Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, the German political foundation. The conference focused on Chinese and Russian political warfare and was attended by some of Europe’s finest foreign policy minds.

In contrast to the Australian debate, British discussions over China feature little in the way of strategic thinking. Beijing is primarily seen through an economic lens, not a geopolitical one (although this is changing). Without access to Chinese technology and investment, the argument in Westminster goes, Britain risks losing its competitiveness. As a result, former prime minister Theresa May accepted technological input from Huawei to build parts of a 5G wireless system.

At the same time, London has gone out of its way to avoid offending the CCP. It has been largely silent about China’s flagrant breaches of the 1997 agreement over Hong Kong. It has not shown any serious interest in Taiwan, and its politicians no longer meet the Dalai Lama.

In recent years universities, pressure groups, publishers, think tanks and news outlets have all bowed to Chinese pressure on a variety of issues. Yet China thrives when political and public debate is quashed.

Like Australia, Britain’s interests are threatened by China. Unlike Australia, we do not yet have a politician who is prepared to so openly call a spade a spade — and stop kowtowing to China.

Andrew Foxall is director of research at the Henry Jackson Society, the London-based international affairs think tank.

Australians need to see and understand the risk posed by China’s increasingly aggressive behaviour. That was Andrew Hastie’s point last week. Australians, he wrote, have to recognise “the reality of the geopolitical struggle before us — its origins, its ideas and its implications for the Indo-Pacific region”. Hastie, who chairs the parliamentary joint committee on intelligence and security, is right.