Bill of rights wrong to shift rule of law to rule of lawyers

It is an irony of the Supreme Court decision that it will return the question of the availability of abortion to state legislatures – which will mean abortion will be readily available in some states and not in others – but this will be a decision for elected representatives and not for the courts. It was the court’s earlier decision of Roe v Wade that effectively removed this issue from these legislative bodies by finding that some state laws restricting abortions contravened a right to privacy that existed in the constitution. As the majority in the most recent decision argues, this was a flight of fancy. It is, however, exactly the kind of judicial creativity that is encouraged by a bill of rights.

This is because a bill of rights transfers political questions from elected members of parliament to unelected judges in the courts. This is not, of course, a criticism of judges who are not appointed to decide political questions and should not be asked to do so. It is important to remember that political questions are not transformed into legal questions if they are handed over to the courts. They remain political questions but ones now decided by the courts and not by politicians.

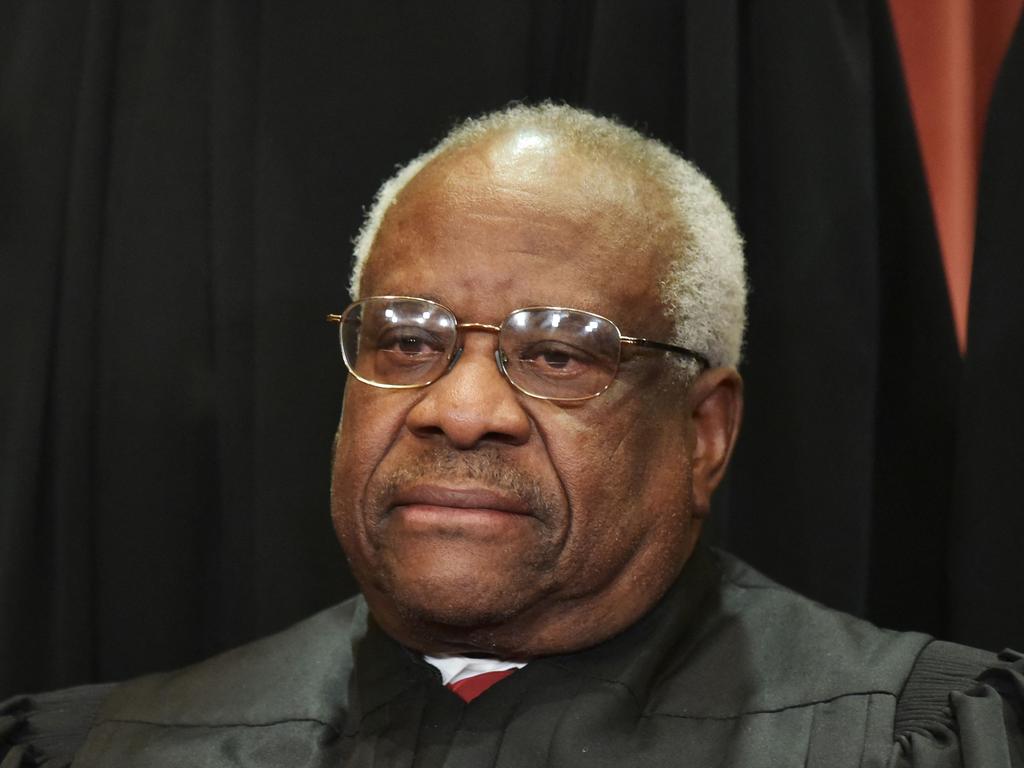

But the bill of rights enshrined in the US Constitution requires hotly contested political issues, such as abortion and same-sex marriage, to be resolved by the Supreme Court and not by the congress and state legislative bodies. As a result, the Supreme Court has become a highly politicised entity and this is reflected in the fiercely partisan confirmation hearings held in the Senate following a new judge’s appointment. It is also why the judges on the court almost invariably vote along party lines depending on whether they have been appointed by Republican or Democrat administrations.

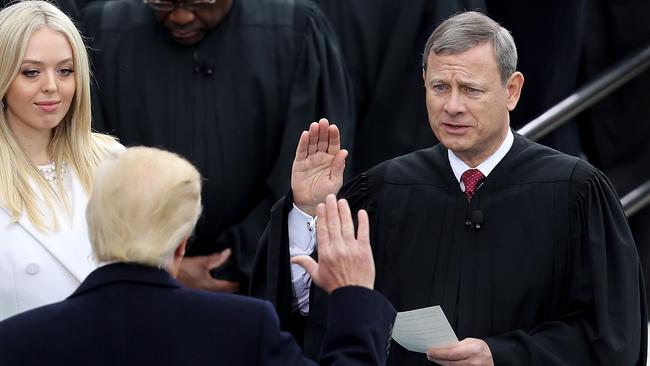

At present those appointed by Republican administrations have a 6-3 majority on the court. One of the factors in Donald Trump’s election as president in 2016 was the knowledge of many of his supporters that the appointment of a Supreme Court justice by a president is a decision that may decide how many contentious political questions will be resolved.

One of the reasons this type of political engineering by judges is inspired by a bill of rights is that its provisions are usually framed with great generality and then require exceptions to be made to the general rule – exceptions whose limits are decided by the courts. So in the case of freedom of speech, which is the subject of protection by the First Amendment to the US Constitution, the requirement that speech shall be “absolutely free” has been significantly qualified over the years to allow, for example, actions in defamation to protect individual reputation, official secrets legislation to prevent damage to national security and criminal penalties for child pornography. But these qualifications are decided by the courts and not by elected legislators.

None of these objections, however, raises any doubts with the academics and legal professional bodies in Australia who constantly call for a bill of rights at both state and federal level. They think judges are better qualified than politicians to decide on contentious issues for our society. So they positively welcome a transfer of power from the parliaments to the courts where they want political issues to be decided.

Indeed, they would like to include in any bill of rights social and economic entitlements to, for example, education and housing, despite these being for centuries budgetary decisions for governments as to how their revenue will be allocated among the many areas in the community that need attention.

Proponents of bills of rights would say those operating in Victoria, Queensland and the ACT differ from the US Bill of Rights because the courts in Australia cannot strike down inconsistent legislation. But the courts are required to interpret all other legislation in a way that is compatible with those bills of rights and public authorities can be the subject of legal proceedings by persons who complain that they have engaged in conduct that is inconsistent with human rights. Naturally, these three Australian jurisdictions have experienced a significant volume of litigation arising out of these provisions.

But that is the point of a bill of rights – it is not about the rule of law but the rule of lawyers.

Michael Sexton’s latest book is Dissenting Opinions.

The US Supreme Court’s decision on abortion underlines the problems with bills of rights. Yet there are still calls for a national bill of rights in Australia along the same lines as those already existing in Victoria, Queensland and the ACT.