It’s impossible to imagine 1970s Australia without Gough Whitlam. He served as PM for fewer than three years, but his political fortunes shaped the decade, culminating in his dramatic dismissal in November 1975. In the lead-up to the constitutional crisis that engulfed his government, The Australian emerged as a powerful critic of Whitlam and his policies. The day after the dismissal, the paper’s editorial lamented his government’s failure to manage the economy, noting its “sad litany of malpractice, inadequacy and incompetence”. The parlous state of the economy was uppermost on the paper’s agenda across the first half of the decade, with one editorial calling out the country’s “worship of the average” and asking why so many workers were happy to embrace a national culture of low expectations. The arrival of colour TV also brought its own cocktail of anxieties, with the paper’s education columnist, Henry Schoenheimer, warning that the temptations of the screen would inevitably surrender impressionable minds to the “galloping consumerism of everything”. At the beginning of the decade, columnist Kenneth Davidson argued that in order to keep pace with the living standards of our two great trading partners, the US and Japan, Australia needed to look to its closest neighbours. “Much of the present philosophy of development,” Davidson wrote, “is based on a vague fear of our relationship with underdeveloped neighbours.”

MARCH TO MEDIOCRITY

- Originally published on July 2, 1975

Average Australia, Average Australia

Come make an Average Australia with me,

And we sang as we faded

Into mediocrity

Come make an Average Australia with me!

We know a lot about the average Australian – too much for our own good. For he threatens to take over our lives, to condemn us forever to an average Australia. We know, for instance, that he fathers 2.3 children, spends an average $191 a year on liquor and tobacco, and in that year drinks an average 130 litres of beer and 9.9 litres of wine.

If he is truly average he earns $152.20 a week. Fellow Australians who are foolish enough to earn more than that rapidly find themselves penalised for doing so. Their tax rates rise rapidly until they find themselves paying 62 cents in the dollar. In clothes of average quality, we drive to our factories and offices in average cars or in average public transport systems, and there perform an average day’s work. And then we retire to our average suburban homes.

Now we have Medibank, admirable in intent but with the potential of providing average medical treatment, provided by average doctors, earning average pay. We turn out university graduates who fade into jobs requiring average academic ability. We build huge office blocks which meet only average architectural standards, if that. Look at Australia, and colour it grey. It is true that the present government has tried to enrich the quality of Australian life through its myriad arts grants. But that does not touch the average man’s life, especially since he cannot afford the above-average expense of palaces of culture like Sydney’s Opera House.

If we are not driving down our average roads, we are walking around with our eyes on the ground. Few of us seems to have a vision splendid; such things no longer seem attainable. What is the reason for this mute acceptance of second-best, this soulless despondency, this sheer lack of spirit? In great part it must lie in the evils which inflation has wrought upon us.

If we are to break out of this ennui, if we are to regain the sense of buoyancy, of freedom, of joy of life, the economy is the place to start. For this slow march toward mediocrity creates an effect in which any aspiration, effort, salary or ambition which exceeds the norm of one’s social group is considered somehow immoral. And this effect pervades our working life.

What average employer would expect his workers to do more than an average day’s work? What unionist would aspire to guide his firm’s destinies? Both are too preoccupied with their traditional confrontation to seek a common goal. And so we are in a three-way bind. To work harder than your peers is industrially and socially unacceptable.

It seems strange that this should be true of Australia. For outside of work, Australians have never been satisfied with the lowest common denominator. We do not aim to produce average cricket teams, or tennis players, or swimmers, or opera singers. We have the will for excellence. Why do we not apply it to the national product? Are we to go the way of Britain, where the pound is falling through the floor because of just such a malaise?

If we grasp the nettle, Australia should be able to avert the fate of even greyer Britain. For with Australia on the move again, we can break out of this worship of the average. But this will be possible only if personal, entrepreneurial, managerial, technical and all workforce talent is given full rein. It must not be penalised by the lowest-common-denominator unions or by governments killing initiative. We will then be in a position to want the best, demand the best and get the best, for our flagging spirits will be restored. Otherwise we will be a people of average financial and spiritual poverty, sadly chanting the anthem above.

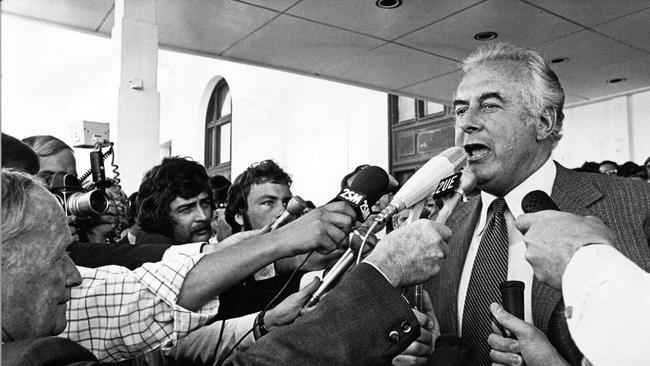

EDITORIAL: ‘SO MUCH GOOD UNDONE’

- First published November 12, 1975

The Governor-General’s decision to sack Gough Whitlam and install Malcolm Fraser to bring about a double dissolution of parliament has brought to an end the constitutional crisis that has laid the country low over the past five weeks and made parliament unworkable. As we have consistently pointed out in The Australian, this was the only course open to Sir John Kerr. It may have seemed, at times, to have been a strictly legalistic approach. It is indeed, and it was high time that the reality of the law was brought into the consideration in Canberra.

There have been far too many shortcuts, on both sides. But we are not a South American republic: we are not some fledgling state bending the old rules left behind by a departing colonial power; we are a sovereign nation in our own right with our own written Constitution and what Mr Whitlam and his colleagues have been about has been the dangerous game of acting as though the law were as they would like it to be, rather than as it is. The rule of law is fundamental to a civilised society. Sir John has resolved the immediate constitutional crisis; it is now for the people to resolve the political crisis.

Sir John’s decision brings to an end the slanging match in Canberra which has been distorting the realities. It brings to an end the bluff and double-bluff in the brilliant poker hand Mr Whitlam has been playing – even so much as seeming to try to force the banks to supply the finance with which he could govern without parliamentary authority. Sir John’s move is a major contribution to the way we run affairs and the way in which our leaders should conduct themselves. It leaves the image of the strident, confident Mr Whitlam, which he would have us accept, sadly dented and certainly stripped of credibility.

So much for Mr Whitlam’s insistence that only he and his ministers could advise the Governor-General; so much for those inspired leaks from the Prime Minister’s office about what the Governor-General was telling Mr Fraser. Alas, having set out to “smash” the Senate’s power, Mr Whitlam has ended up, for the present period at least, in confirming and strengthening it. Sir John’s decision gives people a chance to speak. It brings us back to the basic issues. These are the state of the nation and the record of the government over the past three years.

No federal government came to office with more goodwill than Mr Whitlam’s; there have been few with such promise. It must be said in its favour that it brought about a number of major advances. There has been a broad framework of social welfare, of which the most worthwhile, albeit costly, is Medicare – and, although this requires modifications, there is no feeling in the country for its abandonment. The support for wage indexation has helped to forge a major new economic tool.

The Trade Practices Act has promoted competition and given consumers protection. Through the family law legislation the pain and complexities of divorce have been largely eliminated. Education at all levels has been saved and stimulated. There has been large and justified patronage for the arts.

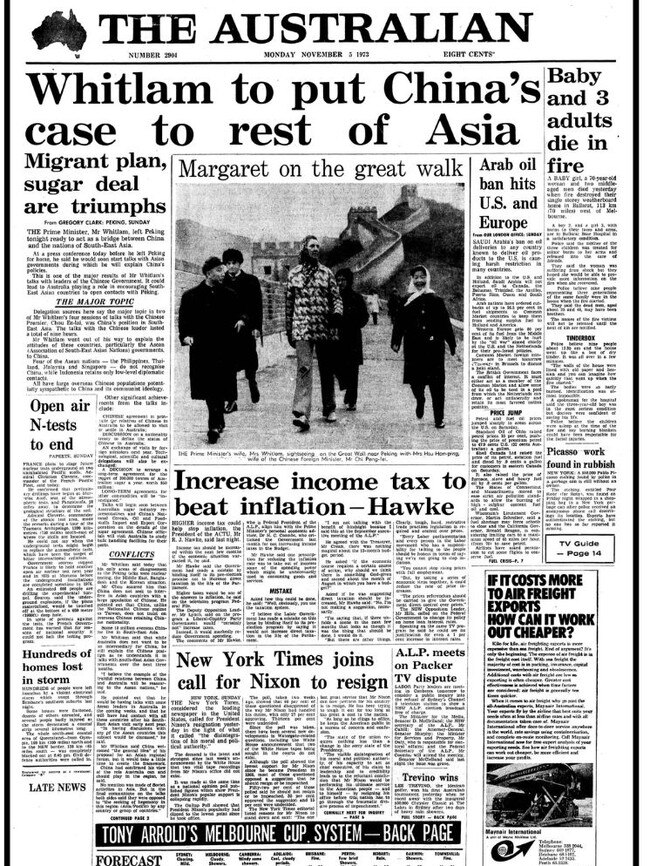

A new, albeit at some times naive, sense of nationalism has been created. The position of women has been enhanced. So has that of Aboriginals. Community health care centres have been expanded. In the area of defence there has been healthy concentration on defending Australia rather than a forward position. Likewise, in foreign affairs, the recognition of China was a major breakthrough that will not be diminished by the silly fussing with Third World affairs.

But so much of the good has been undone. No country can prosper, develop or sustain and expand a generous social program for the people unless it can afford it. And, sadly, at present we cannot. All the economic indicators today point to a high degree of uncertainty throughout the entire community.

The government has shown a broad inability to manage the economy. It has achieved record inflation, record interest rates, record unemployment. Mr Whitlam has gone through three treasurers in three years – which must be a record of sorts.

After the Gair Affair we have had the Morosi Affair and the Loans Affair. The first was sordid. The latter was bedevilled with mendacity, attempts to bypass the states and a straight-out violation of the Constitution. The result, unprecedented in this country, was the sacking of two cabinet ministers for misleading the Prime Minister, parliament and the people.

It is a sad litany of malpractice, inadequacy and incompetence – albeit with some redeeming features. This record of the government now becomes the issue before the people. Mr Whitlam has used every device available to him, and some that clearly were not legitimately available, to avoid a general election. He has failed. The rule of law has prevailed. Let us now go into the campaign and vote.

CHARGING INTO THE ‘70S

The 1970s could turn out to be the most decisive period in Australia’s economic history. At the turn of the century, Australians enjoyed living standards significantly in advance of the rest of the world.

Today, Australia still enjoys a ranking among the top 10 most affluent nations in the world – but only just.

It is still in the position of being able consciously to choose to stay in the front rank of affluent nations. But this choice may no longer be possible at the beginning of the 1980s. On present trends, Japanese workers will be enjoying higher real wages than Australian workers by the end of the 1970s. By the end of the century, both Japan and the US will be post-industrial societies with real incomes up to five times higher than Australia.

This prospect has widespread ramifications. The quality of life of the average Japanese will be as far in advance of the average Australian – just as the position was the reverse at the beginning of the ’50s.

Culturally, too, Australia is bound to become the satellite of our two largest trading partners.

Australia still has a chance of becoming a post-industrial society at the end of the century, but only if there is a complete change in the underlying philosophy of our development.

Much of the present philosophy of development is based on a vague fear of our relationship with our underdeveloped neighbours.

The far more serious question of just what sort of political, economic and cultural relationship Australia will have with the two superpowers of the Pacific never seems to be considered.

Australia’s only chance of maintaining some degree of meaningful independence from these two powers in the next 30 years is to maintain such growth in the economy that our living standards keep pace with US growth and Japanese living standards. Whether our population is 20 million or 30 million by the year 2000 will make no difference to Australia’s relationship with the Pacific superpowers.

Australia enters the 1970s with a windfall gain in minerals which should ensure a healthy balance of payments until the mid-1970s. This breathing space should be used now to make some of the necessary structural readjustments to the economy to improve both the productivity of labour and capital.

Industry is entitled to know what sort of environment they will have in which to operate during the 1970s. It is difficult to recall one government pronouncement on long-term economic policy during the 1960s that was anything other than platitudinous. The significant statements on the economy have been made by agencies of government, such as Treasury in its supplementary White Papers, the Tariff Board in its last three annual reports and possibly recent Arbitration Commission judgments in national wages cases.

The abdication of government responsibility during the 1960s occurred because the Coalition was hopelessly split on long-term objectives.

Consequently, Australia has drifted into the status of a managed economy where decisions have been made, basically, as a response to whichever of the competing interest groups is strongest at any given time.

This may be what politics is all about, but if the system continues into the 1970s Australia’s future low status in the Pacific is assured.

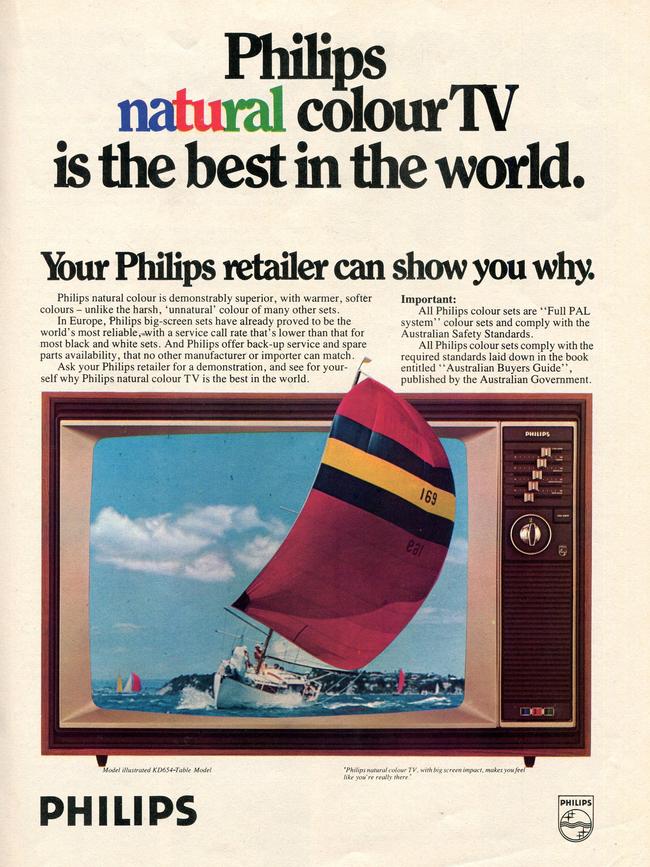

Our education columnist railed against the waste in converting black-and-white television sets. Why not bring every school book into colour as an alternative?

COLOUR TV: IS THIS SPLURGE NECESSARY?

- By Henry Schoenheimer. First published November 12, 1973

All the statistical evidence is that, on average, Australian children and adolescents watch television for somewhere between 20 and 25 hours a week; and the research and informed educational judgment combine to assert that for the very great bulk of that time, what they watch varies from rubbish down.

From the educational point of view, it consists largely of invitations to ape the violence, greed and other immorality of featured programs; in-depth come-ons to wreck their health with cigarettes, tooth-rotting, health-threatening confectionery, foods and drinks; the titillation of precocious sexuality; and the overall incessant urge to galloping consumerism of everything. Now you wouldn’t really think the kids needed a great deal of expensive inducement to extend their long and faithful buttock-wearing, brain-passive vigil before the talking eye. Apparently you’d be wrong. In the three years after 1975, colour TV sets are estimated to cost a fraction under $500 million.

I’m not sure what the country’s team of poverty researchers would want us to do with a billion dollars, or even half a billion, in the sleazy squalid slums of Redfern and Fitzroy – that is if ever the descendants of the sun-bronzed pioneers gritted their sugar-surviving teeth and determined to tough it out with mere black-and-white day-and-night picture-shows in the lounge-room. But just for starters, the Australian school book industry is presently calculated to be worth $16m a year, and by doubling that cost you could bring every school book into colour.

Even so, name your own alternatives for the rest of this money. Just as an off-the-cuff suggestion, it’s enough to keep alive and healthy the millions of kids who starve to death each year on this planet. Still, even if we can’t help the little perishers, we’ll shortly be able to watch them doing it – and in full colour too, Gough bless us all.

The Australian is turning 60 and we invite you to celebrate with us. Our first special series to mark the event is: Six Decades in Six Weeks, counting down to the 60th birthday of the masthead on July 15. Every day for the coming weeks we will bring you a selection of The Australian’s journalism of the past 60 years, from news stories to features, pictures, commentary and cartoons. Today we cover commentary. See the full series here.