Immigration has such ramifications for the economy, for society and potentially for security too that it has to be closely managed by national governments; yet too often it’s effectively subcontracted out to educational bodies, using overseas students as cash cows, businesses too shortsighted to train and pay locals, or even to people smugglers preying on those desperate for a better life.

Mass migration means downward pressure on wages, upward pressure on housing costs and massive pressure on infrastructure of every type. Often it strains social cohesion too as newcomers from very different backgrounds struggle to integrate. Illegal migration at scale is even more problematic as it’s a form of peaceful invasion and a threat to national sovereignty as well as living standards.

Reducing the current very high levels of migration from comparatively poor to comparatively rich countries means overcoming the vested interests of those who benefit from it: namely schools and colleges selling an immigration outcome in the guise of “export education”; employers who want cheap and abundant surplus labour; and ethnic activists looking for numbers to boost their political clout.

It also means resisting the policy makers who think all migration is good migration because it helps to dilute an “oppressive” Judaeo-Christian culture or because it supposedly boosts the economy and enriches a previously sterile “Anglo” culture.

This is only true if the newcomers are, on average, at least as skilled and sophisticated as the existing population – a very dubious proposition, given that the temporary cessation of immigration during the pandemic did not lead to a sudden shortage of brain surgeons and rocket scientists but of cleaners, drivers, carers, waiters and pickers.

Immigration certainly boosts overall GDP but not necessarily GDP per person (which is the best proxy for living standards and economic strength) and can often be a lazy substitute for productivity-boosting economic reform.

Stopping illegal migration means resisting bleeding heart pleas that rich countries have no right to refuse entry to people from poorer ones, even if those demanding “asylum” have passed through several safe countries to their preferred destinations where jobs are plentiful and social welfare generous. It also means finding the political will to bypass the judicial activism that’s plagued immigration detention in Australia and sabotaged the recent British policy to send irregular maritime arrivals to Rwanda.

Decision-makers are often reluctant to canvas changes to immigration policy for fear of upsetting migrants and being called racist. Because vast numbers of people from poorer countries would like to live in richer ones, this reluctance to discuss immigration means that migrant numbers tend inexorably to increase and host countries’ cultures tend inevitably to change. The risk is that countries’ characters could quite substantially evolve and the paradox is this could be the very last thing that most migrants want.

Migrants only move to countries they regard as being in some significant way better than their homeland. In effect, they are voting with their feet in favour of their preferred destination and against their current homeland. At least for the vast majority, they’re coming not to change us but to join us.

But over time, in sufficient numbers, change us they do. Mostly, but not always for good. Most migrants understand this. That’s why it’s almost impossible to find a recent immigrant who’s critical of the country, who isn’t somewhat concerned about subsequent immigrants, and who doesn’t readily understand that IT consultants from India, say, will generally have less trouble settling in than, say, illiterate farmers from sub-Saharan Africa or brainwashed Islamists from Gaza; hence the observation that it’s usually the last one in who wants to lock the door.

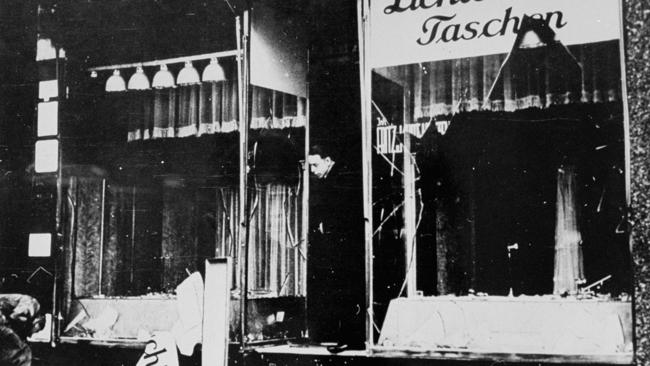

Thanks to many individual migrants, countries like Australia have finer food, better universities and a more sophisticated high culture. Without migrants, many industries would find it harder to operate. But in part because of recent migrants from the Middle East, as well as neo-Marxist ideas about Jews’ “white privilege”, there’s also massively increased anti-Semitism, typified by our October 9 day of infamy on the steps of the Sydney Opera House when a large crowd marched to the Sydney Opera House chanting “F*** the Jews” and what sounded very much like “gas the Jews”, but that NSW police forensically analysed to be “where’s the Jews”, as if that made it alright.

In most Western countries the anti-Jewish tirades, near riots, and mini-Kristallnachts started even before Israel’s just war against Hamas in the aftermath of the October 7 atrocity. Yet authorities have danced around prosecuting or deporting hate preachers, clearing encampments and banning disruptive protests because they don’t want to be accused of a non-existent Islamophobia, especially by the militant leaders of poorly integrated immigrant communities, which in Australia and even more in Britain, now comprise a large proportion of some cabinet ministers’ electorates.

Countries have a right and even a duty to keep their character. This is especially important in countries like Australia and New Zealand where fully 30 per cent of the population is overseas-born, double the rate in the US and UK.

Having a non-discriminatory immigration policy doesn’t mean accepting everyone from anywhere all the time. Especially as their migrant sources diversify, settler societies need a strong civic patriotism to replace fading ethnic and religious ones.

That means a clear insistence that migrants to Australia join Team Australia rather than simply live in Hotel Australia. The expectation has to be that migrants integrate quickly and eventually assimilate. If it’s not to mean becoming a nation of jostling tribes, being “multicultural” can mean no more than a measured approach to integrating and assimilating, perhaps in the next generation.

That need not mean loss of community distinctiveness. Jewish Australians for instance have managed to maintain their religious and cultural personalities across multiple generations, and also their interest in Israel, while, if anything, over-contributing to our national success and helping to shape our national character.

Sovereign nations can’t let immigrants self-select via paying an educational institution or a people smuggler.Simply getting here can’t mean staying here. The best way to ensure immigration is working for our existing citizens as well as for our new migrants is to base it around specific employment: if someone has a specific job offer, from a specific employer, at a fair market wage, with a foreign worker tax to be paid by the employer to the government to help cover infrastructure, and can stay employed and out of trouble for five years, then that person and his or her immediate dependants would undoubtedly make a fine Australian family, paying tax and contributing meaningfully from day one.

In the West, in Europe no less than in North America, there’s alarm at the damage done by uncontrolled migration. Irregular migration has to be stopped, preferably with “dreamers” swiftly and safely returned to their place of origin.

Even legal migration has to be run much more obviously for host countries’ benefit. This is especially important for settler societies, like ours, if the social licence for immigration is to be preserved, and is not a denial of our Australian nationhood, with an Indigenous heritage, a British foundation and an immigrant character, but the only way to preserve it.

Tony Abbott was prime minister of from 2013 to 2015. This article is based on remarks he delivered last week to the Danube Institute-Heritage Foundation forum in Washington.

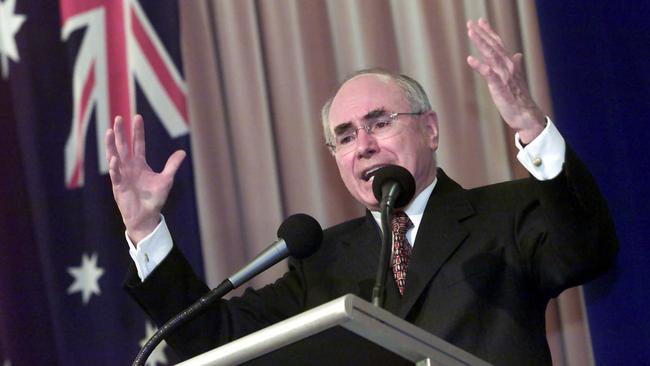

John Howard was right when he famously declared, in the run-up to the 2001 election: “We shall decide who comes to this country and the circumstances under which they come”.