There was, for sure, some consolation in seeing the epithet used – so unusually – as a term of praise: given the trend, it may be only a matter of time before family newspapers such as this one feel obliged to transcribe it as “c*nser**t*ve” for fear of offending squeamish readers.

But at the risk of being old-fashioned, it still seems worth sticking to the view that sensible discussion is impossible if words are used in ways entirely unrelated to their meaning.

It is true that conservatism has no master text that defines an orthodoxy, nor has it ever suffered from the afflictions of an ideology. A river fed by many converging streams, it has, at least in the British tradition, always been more of a disposition – a way of thinking about politics – than a doctrine.

But if there is an enduring essence to the conservative disposition it is its emphasis on prudence. That emphasis, which is as ancient as the Western intellectual tradition, found its towering champion in Aristotle, who first identified prudence as the greatest political virtue.

For Aristotle, as for Cicero who followed in his footsteps, prudence did not mean being timorous or indecisive; it meant thinking about how to advance the good of the community while avoiding both the hubris of demagogues and the arrogance of those who ignore the complexity, messiness and unpredictability of social life.

Relying on the lessons of experience rather than on those of the academy, the phronimos or “prudent man” was the leader who, like Pericles, knew how much he did not know about the shoals that lay ahead.

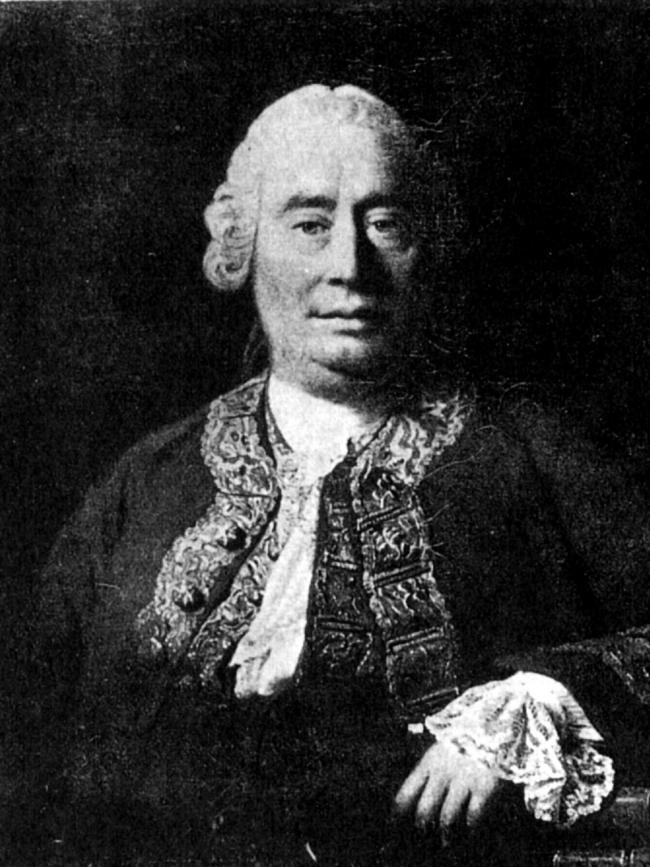

It was those insights Sir Edward Coke, David Hume and Edmund Burke drew on in fashioning the British style of conservative thought.

Coke, the greatest jurist of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, laid the foundations when he argued that the wisdom of the common law came not from any reliance on divine reason or scholastic logic but from an incessant ability to experiment, learn and adapt, revising when needed but always respecting the judgment of “many successions of grave and learned men”.

Repeating with relish Chaucer’s proverb “Out of the old fields must spring and grow the new corn”, Coke rejected traditionalism, “the dead faith of the living”, while revering tradition, “the living faith of the dead”.

It was therefore natural that Hume, in reflecting on the disasters caused by attempts to make the world anew, should stress that “as human society is in perpetual flux”, liberty and stability could be reconciled only through a “science of prudence” that ensured each “new brood nearly follow (in) the path of their fathers”, while using “trials and experiments” to devise those changes that were indispensable.

Equally, Burke, faced with the utopian aspirations and dystopian outcomes of the French Revolution, warned that “the science of constructing a commonwealth, or renovating it, or reforming it, is, like every other experimental science, not to be taught a priori”. As “very plausible schemes, with very pleasing commencements, often have shameful and lamentable conclusions”, society ran enormous risks if, succumbing to the “floating fancies and fashions” of the day, it allowed the “moral geometers” who claimed to hold the definitive answer to a social ill to lock their purported solutions into place.

None of that was a counsel of immobility. On the contrary, Burke was, without a doubt, the greatest reformer of his time. His Economical Reform Act of 1782 set the basis for the sweeping administrative reforms of the 19th century, while his relentless criticisms of the cruelty of empire established the doctrine, subsequently articulated by the House of Commons Committee on Aborigines in 1837, that “He who has made Great Britain what she is will enquire at our hands how we have employed our influence”.

When Burke said “A state without the means of some change, is without the means of its conservation”, he therefore meant exactly that. But rather than being fuelled by the allure of a gilded future, change had to be guided by a realistic appraisal of experience and an acute awareness of the scope for error.

More than anything, that was the spirit that infused the conservatism that developed in the British dominions.

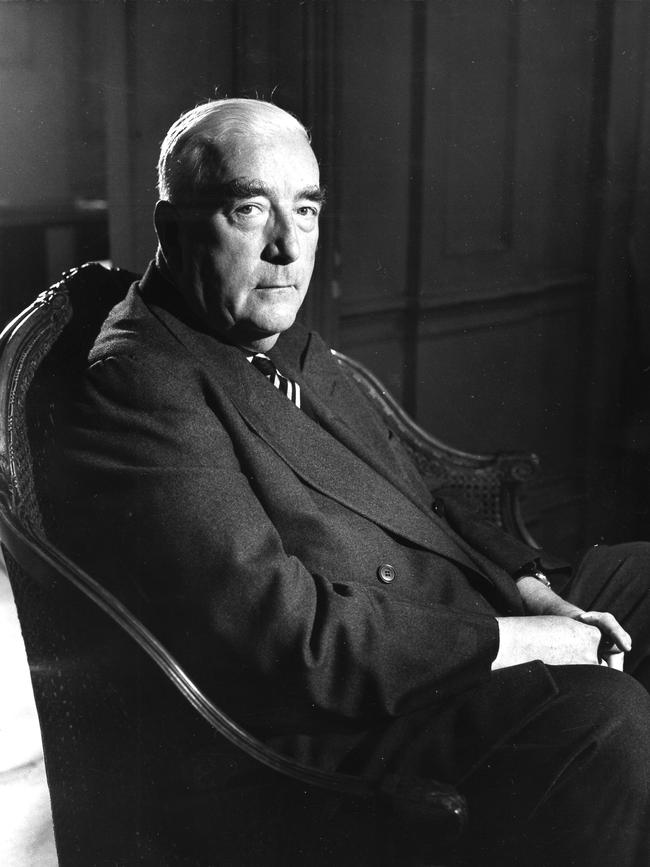

It was consequently no accident that its post-war Canadian political incarnation called itself the Progressive Conservative Party, marrying progress with continuity. Nor was it an accident that Robert Menzies, in creating a party devoted to forging a strong, prosperous and cohesive nation, sharply distinguished it from “a party of reaction (or) negation”, while equally sharply distinguishing its incrementalism from the “leap to glory” promises of its opponents.

The new party’s philosophy saw life not as holding out dangers to be avoided but as offering opportunities to be welcomed – opportunities that should be equally available to all, including Indigenous Australians. Paul Hasluck, Menzies’ long-serving minister for territories, forcefully set that out in 1961 when he convinced the premiers that Indigenous Australians deserved to be “members of a single Australian community enjoying the same rights, privileges and obligations as other Australians”, with any special measures being “temporary measures, not based on race” that would “assist them to make the transition”.

Many glaring mistakes and omissions were made in that approach’s implementation; but now as then, Hasluck’s positive vision, which is the antithesis of the voice, remains the better way. Its aspiration is one all Australians can share; it channels this nation’s energy to a goal that unites rather than divides, banishing racial distinctions that should never have tainted our Constitution; and while the voice constitutionally entrenches a mechanism that has not just failed to make things better but has invariably made them worse, it retains the flexibility prudence demands.

In no area of policy is that flexibility more important – for if a lesson emerges from our rare successes and frequent mishaps, it is that not only are there no utopias, there are no solutions valid for all time. There are only approximations, only the continuing struggle for decency, only the need to adapt and adjust as we go.

It may be that the politics of prudence has gone out of style. The politics of atonement, which places greater weight on being righteous than on being right, is certainly more appealing, promising to painlessly dispel the canker of guilt. But don’t call that approach, and its latest incarnation in the voice, conservative. A disease presented as a cure, all it will conserve are yesterday’s wounds and today’s errors.

Reading a slew of columns last weekend that described the Indigenous voice to parliament as “conservative”, it was hard not to sink, like John Bunyan’s Pilgrim, into the slough of despond.