But the fact that Australia’s leading Muslim organisations have steadfastly refused to condemn the vilely anti-Semitic sermons being preached in Sydney mosques should not be viewed as just one more confirmation that when it comes to racism, Jews don’t count. Rather, it points to issues that go to the heart of contemporary Islam.

At the origin of those issues is the dramatic unravelling of the Islamic world that occurred in the second half of the 19th century. The Ottoman Empire’s progressive disintegration after the Greek War of Independence that began in 1821; the consolidation of European rule in North Africa and Islamic East Asia; and the calamitous failure of the Indian Mutiny in 1857, which precipitated the end of the Mughal empire: together, those seemingly apocalyptic changes triggered a pervasive crisis, as Muslims suddenly faced European dominance.

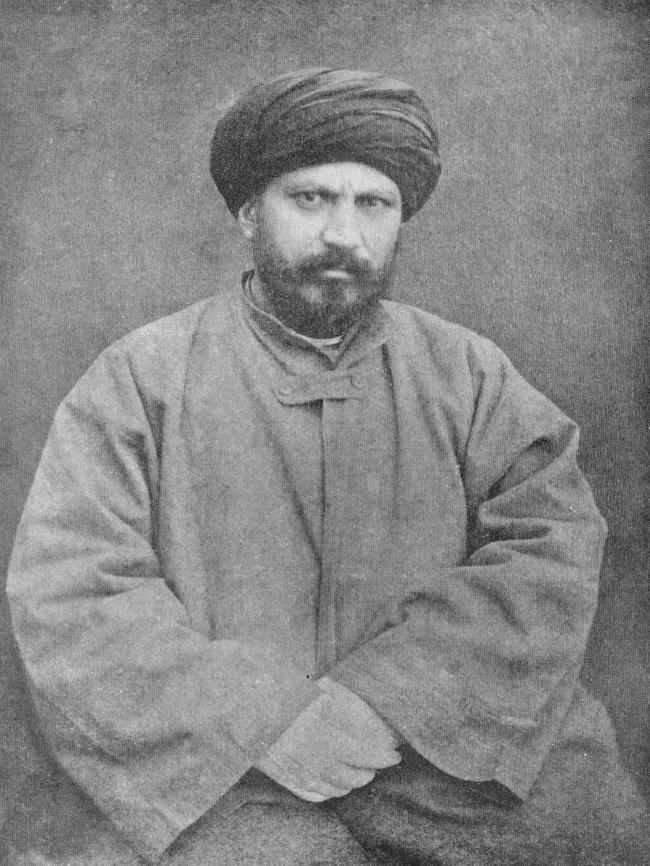

While the response took many forms, the belief that the crisis was primarily a crisis of faith provided a common refrain. As Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1838–1897), who played a crucial role in the subsequent redefinition of Islam, put it, “if someone asks, why are the Muslims in such a condition? I answer: when they were truly Muslims, they were what they were and the world bears witness to their excellence”.

The remedy was therefore seen as lying in a return to an unadulterated form of Islam, through a “re-form” that combined “tajdid”, restoration, with “islah”, repair.

There had, of course, been earlier moves in that direction, most notably those associated with the 18th century cleric Muhammad al-Wahhab, who advocated reverting to the path of the “salaf” or “pious predecessors”. But Salafism was almost entirely confined to the Arabian peninsula. In contrast, far-reaching improvements in transport and communications ensured that the process that got under way in the late 19th century swept, and eventually reshaped, Islam worldwide, gaining impetus as it merged with a ferocious reaction against the West.

That the changes began in India is readily explained. While the Mughal empire’s sophisticated Muslim elite retained its Persian-Turkic heritage, the practical realities of ruling a largely Hindu country had forged an anomalous, highly syncretic version of Islam that accepted inter-marriage and celebrated Hindu festivals. Reacting, once the empire had collapsed, against that “corruption” of the true faith, the Deobandi movement, established in 1866, sought to “cleanse” Islam of “impurities” and ensure Muslims avoided the “contamination” that came from mixing with “pagans”.

Although the Deobandi movement was originally pietistic rather than political, the rapid diffusion of its outlook had two momentous consequences. To begin with, the emphasis on ridding Islam of “impurities” set off unprecedented attacks on supposed heretics, especially the Bahais and Ahmadis, who were later subjected to often murderous persecution in Islamic lands.

At the same time, Muslims became increasingly hostile to non-Muslims, to the extent that Rafiauddin Ahmed, in his study of late 19th century Bengal, concludes that by 1905, communal relations had been so severely damaged that long-term co-existence between Muslims and Hindus was impossible.

Those features – internal persecution and external hostility – became only more pronounced as Deobandi’s many successors pursued its program of taking Islam back to its roots. That Islam’s “purification” would go hand in hand with greater intolerance was predictable. As Remi Brague, emeritus professor of Arabic and religious philosophy at the Sorbonne, argues in On Islam (2023), Islam’s defining components – the Koran, the Hadith or “statements of the prophet”, and the “good example” (as it is referred to in Islamic theology) set by the deeds of Muhammad – are, when read strictly, permeated by hatred and calls to violence that go far beyond anything that can be found in Islam’s Abrahamic predecessors.

And they are, Brague shows, particularly marked by venomous attacks on Jews, who, because they are inherently “treacherous”, “ungrateful” and “stubborn”, can – in a well-known Arabic phrase an Israeli minister recently hurled back at Hamas – be legitimately regarded “as animals” or (if the purpose is to extract their alleged wealth) even tortured to death.

It is undoubtedly true that there are incendiary statements in the Jewish and Christian bibles too. But because the Koran is viewed not as the work of men but as the perfectly transcribed word of God, Islam has, since the comprehensive defeat of the Mutazilite school of Islamic theology at the end of the 9th century AD, imposed far stricter limits on scriptural interpretation than Judaism and Christianity.

The great Muslim scholar Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406) put it well when he wrote that in Islam, interpretation’s principal purpose is simply “to refute innovators who deviate from Muslim orthodoxy”.

The veil provides an obvious example of the harm that has done to doctrinal modernisation. That women must be veiled is mentioned twice in the Koran (XXIV, 31 et XXXIII, 59); it is, however, also specified in 1 Corinthians 11, 3-16.

But in line with the allegorical approaches to scripture pioneered by Clement (ca. 156-215) and Origen (ca. 185-254), Saint Paul’s statement was soon reinterpreted as merely mandating modesty.

In Islam, on the other hand, the extensive theological commentary on the Quranic injunction almost always took the veil for granted, limiting itself to trivial questions such as its allowed length or colour – with the result that just a few days ago, Roya Heshmati was whipped 74 times while chained to an iron frame for defying Iran’s veiling laws.

Ebrahim Moosa, professor of Islamic Studies at Indiana’s University of Notre Dame, is surely right that many “religiously literate contemporary Muslims” have their “sensibility shaken” when they witness such barbaric acts or hear horrifying sermons; but he is also right that what they are seeing is “genuine” Islam at work.

And far from being surprised at the appalling silence of Australia’s leading Islamic organisations, the late Muhammad Shahrur, a prominent Syrian public intellectual, would have seen it as yet another confirmation that “the ulama’s (clerical establishment) interpretations (of Islam) are not in fact too different from those of the Islamists”. Islam’s problem, he insisted, was not solely or mainly unchecked extremism at its fringe; it was the entrenched extremism of its mainstream, which instead of undermining the fringe, gave it legitimacy.

Exactly a century ago, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk abolished the califate and closed the madrasahs, or religious schools, later moving to outlaw the tariqas (Sufi orders) and dervish lodges, which had violently resisted the changes he had announced.

Determined to bring “the people of the Turkish Republic into a state of society entirely modern in spirit and form”, Ataturk was convinced Islam, left to its own devices, would ultimately stand in “the way of civilisation”. Whatever one may think of his methods, history has not proven him wrong.

Had even the lowliest of parish priests called Muslims “descendants of pigs and monkeys”, keffiyeh-clad crowds would have stormed the premises within moments. And well before the Prime Minister had added his voice to the outcry, the church hierarchy would have issued torrents of heartfelt apologies.