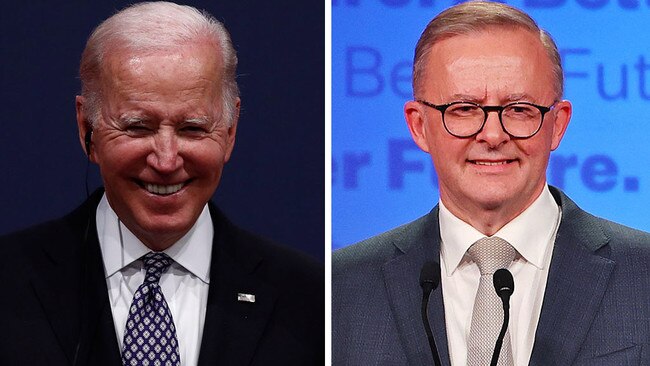

The two men will have more in common, in terms of policy, politics and personality, than any two leaders of the US and Australia since John Howard and George Bush.

“Biden is going to feel as though he has a fellow traveller; it’ll be like two guys in a pub,” one well-placed Washington official put it on Monday (Tuesday AEST).

Combating climate change and creating union jobs are two of President Biden’s favourite topics, peppered liberally throughout his domestic speeches.

Mr Albanese, leader of the union-aligned and funded Labor Party, who campaigned on climate change, is likely to prove a more receptive audience.

Australia’s relationship with the US under successive Coalition prime ministers was strong and successful, spawning most recently a new security pact, AUKUS, and an emboldened, more co-ordinated Quad group of nations determined to stand up to China.

But Scott Morrison and Joe Biden, understandably, didn’t gel with each other in the way Mr Albanese and Joe Biden could. However unfairly, Democrats never really believed the Coalition’s heart was in it when it came to reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

The president very publicly forgot Mr Morrison’s name in September after a period of intense negotiations over AUKUS. And the former PM was among the president’s last phone calls to close allies when the US withdrew suddenly from Afghanistan a month earlier.

Joe Biden and Anthony Albanese can chat domestic political strategy too, both for instance relying on support from increasingly radical wings of their centre-left parties.

The Biden administration is obsessed with gender, LGBTIQ and race issues in a way the Coalition government was not, and the new Labor government almost certainly will be.

The similarities don’t stop at politics and policy.

Mr Albanese’s background as child of a single mother who grew up in council housing in Sydney’s west will resonate with ‘the scrappy kid from Scranton, Joe Biden’, who likes to dwell on his relatively humble background too.

The new prime minister is a more likely kindred spirit for the down to Earth president than the leaders of other US allies, such as Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson in London, born in New York’s posh upper east side, or the silver spoon scion of political royalty in Ottawa, Justin Trudeau, who at 50, is more than a generation younger than Biden.

Mr Albanese may even want to play down the “non-practising” aspect of his Catholicism when he talks to a president who takes his Catholic faith seriously.

None of this is to guarantee a seamless relationship. There’s more to governments than their leaders.

“The president would have worked well with either leader but knowing both their personalities, I think there’ll be a natural affinity between Mr Albanese and Joe Biden, a good chemistry,” Jeffrey Bleich, Barack Obama’s ambassador to Australia from 2009 to 2013, told The Australian.

Some US officials were on Monday (Tuesday AEST) sending each other a picture of Mr Albanese and foreign minister Penny Wong being briefed by Andrew Shearer, the Coalition’s top intelligence adviser, ahead of their arrival in Tokyo, as a way of reassuring each other the new Labor government’s foreign policy wouldn’t be changing.

It’s early days yet, of course. A Labor clean out of the upper ranks of the bureaucracy, or pressure from parts of the Labor Party that would prefer a foreign policy more “independent” of Washington, could dash such hopes.

For now though, there’s only upside for Australia’s standing with the Biden administration.

Not only have the awkward aspects of any relationship between leaders hailing from the opposite sides of the political spectrum been swept away, a strong personal bond is in the offing.

Anthony Albanese’s meeting with President Biden in Tokyo this afternoon could herald the start of a beautiful friendship of sorts, elevating Australia’s influence further in the White House.